I have noted with growing despair the xenophobia which is becoming a political commonplace this election cycle. On the left it’s about house prices.* But this post is not about racism; it’s about development.

The national median house price is $415,000, a figure skewed substantially upwards by the extraordinary cost of housing in Auckland. But you can buy a three bedroom house in Taumarunui for $26,000, or for $67,000 in Tokoroa. These are extreme examples, but for considerably less than half the median price you can buy a charming colonial villa in Tapanui ($149,500). For a little more than half the median you can buy a newly-renovated house on an acre in central Gisborne ($225,000). Similar houses are available for not very much more money in larger regional centres like Dunedin and New Plymouth, and that’s without considering many apartments, townhouses and more modest types of dwelling.

There are houses out there: there just aren’t jobs to go with them.

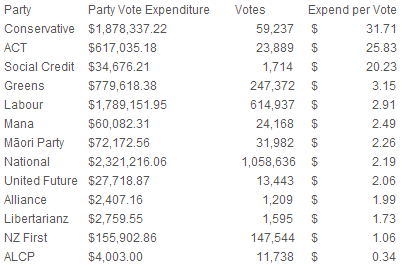

The chart above shows income and employment growth by region, and this is why the houses are so cheap. The growth is just not there. (From the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment Regional Economic Activity Report 2013).

Opportunity

It’s not just jobs, though; there’s more to life than work. People need confidence in their opportunities in a new place before they will, as Jolisa Gracewood says, buy shares in that community by owning or renting a house there and settling down. They need schools and hospitals and civic institutions and a sense of belonging, they need certainty about their community’s future, and their future within it.

The community likewise needs needs certainty in its new arrivals. A gold rush or an oil boom might provide jobs and cash, but it doesn’t provide certainty for either group. Certainty — and opportunity — comes from deep and sustained development. The fly-in/fly-out mining towns in Australia are a good example, and while that industry has been instrumental in maintaining Australia’s robust economy, its direct value to the regions has been limited — trickling down, lifting all boats — without the adoption of targeted development initiatives such as Royalties for Regions, which seek to return a share of the proceeds of industry to local communities.

As Eric Crampton said about the census income growth figures, increases in average wages across much of the South Island have been coupled with decreases in population, as people on low incomes move in search of better-paying work. Rob Salmond agreed, saying:

The regions with the supposedly highest median income growth also had some of the worst records in population growth, while the areas whose populations grew the fastest had relatively little change in median incomes.

Returning to the MBIE chart above, notice the regions in the top-right quadrant: the West Coast, Waikato and Taranaki. These are distinguished by two characteristic sectors: dairy, and mining, each of which provides a relatively small number of well-paid jobs within a narrow sector, skewing up the income levels but not necessarily changing the overall development picture very much. As crucial as the dairy industry, in particular, is and will continue to be to New Zealand’s economy, a complete solution to development it sure ain’t. Which is why you can buy an enormous Moorish-inspired villa for $220,000 in the middle of gas and dairy country.

Diversification and specialisation

The object of a regional development policy must be to promote structural change, to create industries and communities that are sustainable in their own right — neither transient nor exhaustible, and which attract people whose commitment is likewise neither transient nor exhaustible. These jobs need to go beyond the traditional churn industries like tourism, hospitality and service; though, of course, these jobs will be needed, they should be incidental to development, not its purpose. They need to be high-value and export-led — unlike, for example, our timber industry, and our wool industry. One of our key advantages here is our reputation for being clean and green — demand for premium food, the safety and quality of which can be assured, and including organic and sustainably-produced, is likely to grow strongly and we seem ill-prepared to meet this opportunity, as just one example. Another example is the potential of MÄori business, which is as yet terribly underutilised.

In New Zealand we talk a lot about the roles of government in distributing wealth, and in ensuring public access to health, education and other scarce resources. These levers are well-recognised and there is at least a moderate degree of bipartisan agreement on their use. This is not the case with regional and economic development strategies, where there are deep practical and ideological divisions between the parties. I can see why the noninterventionist technocratic right parties like ACT and National are reluctant to consider — or even recognise the viability of — the sort of robust, hands-on regional development strategy that will sustainable economic and community growth in regional areas and persuade the frustrated and overcommitted residents of our major cities to risk a change. It will require considerably more input than building roads, granting mining permits and water rights to permit the extraction of value directly from the land. It will require a lot more than public-private partnerships and white-elephant monorails through virgin rainforest. It very likely will require PPPs, roads, and mining rights, though, meaning the left will have to reconsider some of its positions as well. It will require thorough investment in infrastructure, especially transport infrastructure, and purposeful community-building, possibly funded by a deeper cut from mineral royalties, a localised share of revenues from key industries, or loans from the government. It will probably require considerable autonomy devolved to the communities affected, and the strengthening — rather than the weakening, as is currently happening — of local government. It needs to be a little bit New Deal and a little bit Think Big.

Diversity is resilience, and our economy is very narrowly based. That must change. Different regions have their own strengths — environmental and historical, in terms of personnel and capability — and this represents an opportunity to improve the national economy holistically, by strengthening each of its component parts, rather than by building one economic muscle until it threatens to throw everything else out of balance. In many cases these nascent strengths will need considerable augmentation, and some will need to be developed almost from scratch. That requires significant and sustained investment in research and development — contributions to which the National government cut during the time when it was most crucial; when talent needed to be incentivised to stay here, and when industry needed to prepare to take advantage of the recovery, when it arrived. Public-sector research agencies can be beneficial in quite unpredictable ways, and when it comes to blue-sky research, patience can pay off enormously. If you’re reading this over Wi-Fi, you can thank the Australian government’s scientific agency, the CSIRO.

People and places

One obvious and direct means by which the government can influence regional development is by decentralising — by relocating government departments or agencies to regional centres. At a minimum, governments could decline opportunities to actively dismantle regional industries — such as Invermay — for the sake of short-term cost savings or change for its own sake.

It is clear that having a critical mass of mobile public servants all located within a kilometre of each other can increase efficiency and cross-pollination in government and business. Some significant new businesses — such as Xero and Vend — clearly benefit from strong cohabitation and the development of their own start-up cultures. On the other hand, in the past decade telecommuting has become plausible for a large proportion of people whose work is predominantly reading, writing and talking on the phone, and the major reasons it is not more widely used are to do with middle-managers wishing to retain some measure of direct control over their staff, which they label “team culture”.

There are costs and benefits to decentralisation, but it is hard to shake the sense that government, and the public service, are growing increasingly remote from the people whose interests they ostensibly serve. The gap between the experience of living in Auckland or Wellington and living in the rest of the country is vast already, and is likely to grow. Over the long term, as regional development improves, mobility will increase, as the economic and cultural risk of moving to or from a major centre will decrease, and this seems likely to yield an even greater cross-pollination benefit than that sacrificed by decentralisation.

Political laziness from the left

The reason the housing markets in Auckland and Wellington are refusing to cool is because people — both internal and external migrants — want to live where there is opportunity, and Auckland and Wellington is where the opportunity is. Blaming foreigners for the continually-rising house prices in Auckland is counterproductive. It’s lazy populism for the opposition to monger fear on these grounds, and it’s clear why the government is perfectly willing to let them do so: first because it cuts against the left’s political brand, and second, because it frees them from responsibility for what has proven a poor regional growth strategy during their time in government.

Labour and the Greens have taken strong and well-articulated positions in favour of regional development and smart growth but they’ve also gifted the government an opportunity to reframe what is essentially an economic development debate as being about housing and migration, when the former is a symptom and the latter is all but irrelevant. As a consequence the whole discussion gets sucked into an unwinnable partisan slagging-match. This isn’t so much a failure of policy, but a failure of political emphasis. It should be relatively easy to correct: they mainly need to stop complaining about the yellow peril, and start talking about the future of a country where wealth and innovation is spread beyond its main centres.

Although I disagreed with his dismissive attitude towards the marriage equality debate, it seems likely that the once and future member for Napier, Stuart Nash, will be an important member of the Labour caucus in future. Late last year he argued persuasively that the regions are crucial not only for the economic wellbeing of the country, but for the wellbeing of that party, and so for the wider left. As he says:

If any party only holds seats in Akld, Wgtn, Chch and Dunedin, then they don’t have a particularly wide mandate to govern because they haven’t got MPs in caucus putting forward the views of the vast majority of geographic NZ.

To an extent it is understandable that this hasn’t happened yet. Development is hard. It takes a long time and a lot of money, and in a political context where governments change no less often than once per decade, it requires an uncommon degree of accord between increasingly diverse political movements. With the Greens now forming a substantial and apparently-permanent adjunct to Labour on the left, and the emergence of new climate-sceptic and anti-environmentalist sentiments within National and its allies, this is a big ask. But it needs to be done nonetheless. The regions aren’t going to develop themselves; they haven’t got the wealth or the people to do so, because it’s all tied up in tastefully-renovated villas on the North Shore and in Thorndon.

Downsouthing

This is not an entirely theoretical discussion for me. All going to plan, at some point later this year my family and I will move from the KÄpiti Coast to Dunedin. My wife is going to the University of Otago to work on the postgrad study she’s been wanting to do for 10 years. We’d have done it years ago if we could — every time we’ve been to Dunedin, we’ve said we’d move there in a heartbeat if only there was work. Mostly what’s changed now is that I can bring my work with me.

The reason we live out here is because out here is where we could afford to buy a house on one modest Wellington income. The idea was always to move into town at some point, but that has gotten more distant, not closer, over the past five years with Wellington’s housing market proving largely impervious to the recession. So off we go.

We anticipate significant benefits. My wife will be able to do something meaningful with her life other than raise our kids full-time or working as a rest home carer, worthy though both those tasks are. Commuting into Wellington would cost dozens of hours and hundreds of dollars a week, and at some point both of us would inevitably end up far from our young kids when they needed us. But not least among the advantages is the regional arbitrage of continuing to bring in something like a modest Wellington income while living in a place where houses are, very conservatively, $100,000 cheaper.

But there’s the thing: unless you’re privileged enough to work in a field where you can telecommute (and bosses who’ll let you), or unless you work in a literal field, moving from Auckland or Wellington to pretty much anywhere else in the country is a big risk. (In Christchurch, the case is much more complex.) You can move, but for many people, the opportunity is just not there, and the risk of giving up what you have is very great.

The government that raises those opportunities will find favour with those who want to move, those in the regions whose economies and communities are boosted by new growth, and those in the main centres who wish to stay, or must stay, who will have richer opportunities for doing do.

L

* On the right it’s more about asylum seekers (National) and internal threats to the colourblind state (ACT). The only party that seems clean of this is United Future, for which Peter Dunne should be congratulated.