I have little useful to add to the voluminous discussion about who the Labour party will choose to succeed Phil Goff. I’m on the outside. This is Labour’s decision to make, and I don’t have a dog in the fight, except inasmuch as a good opposition and a strong Labour party is going to be crucial to Aotearoa. So I don’t know which way the caucus votes are headed, but like any other punter I have views, and I thought I’d sketch them out anyhow.

First of all it is positive that Goff and King have not stepped down immediately, forcing a bloodletting session 72 hours from the election. Two weeks is, I think, long enough to come to terms with the “new normal” and for a period of sober reflection (and not a little lobbying), but not long enough for reflection to turn to wallowing, or lobbying to degenerate into trench warfare. Leaving it to brew over summer, as some have suggested by arguing Goff should remain until next year, would be the worst of all possible options and I am most pleased they have not chosen this path.

As for the options: after some preliminary research the other day I declared for Team Shearer. I am still somewhat open to persuasion, and he lacked polish on Close Up this evening. But he seems to have unusual intellectual substance and personal gravitas. His relative newness to parliamentary politics is offset by extensive experience in other fields, particularly with the UN where tales of his exploits are fast becoming the stuff of urban legend. Most crucially, I understand he is the least institutionalised or factionalised of the potential leaders, the one with the greatest capacity to wrangle the “political wildebeest” that is the Labour Party, to use Patrick Gower’s excellent phrase. This last is, I believe, the most crucial ability. I said before the election that the next long-term Labour leader will be a Great Uniter, as Clark was (although possibly not in the same way Clark was; awe and fear aren’t the only ways to unite a party), and while there are not broad ideological schisms within the Labour party*, it is deeply dysfunctional in other ways and needs to be deeply reformed. This is a hard task, and it may be that no one leader can manage it, and it may take many years in any case, but it looks to me like Shearer’s external experience and outsider status make him the stronger candidate on this metric.

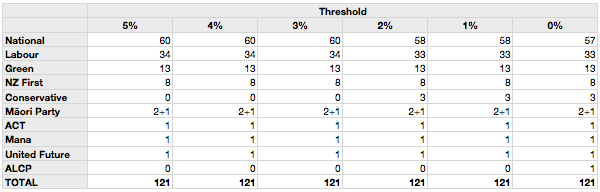

One other thing about Shearer: he seems to have strong support among non-Labourites, including Labour’s ideological opponents. In the Close Up spot he was reluctant to declare Labour a “left-wing party” which will make him unpopular (though I consider this just a statement of fact). I’ve seen some tinfoil-hattery around this — “if people like Farrar and Boag like him, it must be a trap” and so forth. This notion that “the right” has nothing better to do than wreck the Labour party, that every endorsement or kind word is an attempt to undermine, or the suspicion that the muckrakers must surely have some dirt on a favoured candidate borders on a pathology. Such reasoning leads to perverse outcomes, and adherents to this kind of fortress mentality make excuses for poor performance, and congratulate themselves for narrow wins and near losses, rather than challenge themselves to build a strong, disciplined unit capable of winning more robust contests in the future. An example of this in the recent election, where a small but crucial group of Labour supporters abandoned their party, campaigning and voting for New Zealand First in a last-ditch effort to produce an electoral result in their favour, without concern for the strategic effects this might have on the party’s brand and future fortunes. In spite of the lesson of 2008, they swapped sitting MPs Kelvin Davis, Carmel Sepuloni, Carol Beaumont, Rick Barker and Stuart Nash for Winston Peters and his merry band of lightweight cronies. Plenty of dirt there; it would have been a miserable term in government for Phil Goff if the numbers had broken slightly to the left, and (depending on the intransigence of Peters and the other minor parties) one from which the Labour Party may never have properly recovered.

Ironically, Labour has those defectors — about 3% of the electorate if the polls are to be believed — to thank for the opportunity now presented to it by the resounding defeat. If the result had held at around 30% (and NZ First been kept out by the threshold), temptation would have been to revert to the mindset post-2008 election that it had been close enough, that the left had been robbed by the electoral system and the evil media cabal, and that little change was really needed. With support at its worst since the Great Depression, no such delusions can persist, and there is, it would seem, a strong will for reform within the party.

I don’t think the other two likely Davids would make bad leaders either (concerns about Cunliffe that I expressed during the campaign notwithstanding). Cunliffe’s platform with Mahuta is strong, in particular because it will enable the party to reach out to MÄori, which they desperately need to do to remain relevant. Parker reputedly has greater caucus support than Cunliffe, and he is also apparently standing with Robertson, who is also said to be standing for the leadership himself. All three Davids are talking about reform, and it will be harder for any of them to paper over the cracks or pretend that nothing is wrong, as Goff and King did. But whatever their will, it is not clear that Davids Cunliffe or Parker have the same conflict-resolution, negotiation and strategic development experience that Shearer does. And they are themselves a part of the problem, having been ministers (however excellent) under Clark, and supporting and sharing responsibility for the abysmal strategy and see-no-evil mentality evident within Labour since 2008.

But the party must do what is right for the party. It is important that the final decision remains with the caucus because as the past year has shown, no matter what the public and commentariat thinks no leader can be effective who is at odds with his team. Ideological congruence also matters; Shearer may be have the best skillset for the reform job, but he may legitimately be considered too centrist by the caucus.

I’ve always been clear that I want the NZ left to win, but I want them to have to work hard for it. I don’t want easy outs, excuses or complacency; I want Labour to be able to beat the toughest, because that’s what produces the smartest strategy and the strongest leaders, and the best contest of ideas. I am sure principled right-wingers hold similar views; they are just as sick as I am of a dysfunctional opposition obsessed with its own faction-wars and delusions of past glory, stuck in the intellectual ruts and lacking in strategic and institutional competence, even though it might make their electoral challenge easier. Good political parties don’t fear the contest of ideas; they embrace it. So my hope is that Labour does not concern itself overmuch with second-guessing the views of their ideological foes, or those on the periphery, but puts the candidates through a thorough triage process and then lets him get on with the job of putting their party back together. It’s not a trap, it’s a challenge.

L

* The lack of ideological diversity is a problem; a healthy political movement should always be in ferment. But it is not the most pressing problem facing the party at present.