Hat tipped to Paul McBeth for this one.

As one side engages in some tentative but hugely premature triumphalism, and the other side points the accusatory finger, a sleeping giant awakes. This man — our Nixon, in whom we apparently see ourselves as we really are — has rekindled the fire which once consumed the hearts and minds of the nation (and the knickers of untold women old enough to know better) and thrown himself with renewed fervour into the task of “getting his old job back”.

Thanks either to wicked humour or outright shamelessness on the part of Auckland University political science staff, Winston Peters has been granted the unlikeliest of springboards to launch his 2010 campaign to return to the Beehive in 2011: a lecture to (presumably first year) political science students on the MMP political system. Of course, if they’d wanted a serious lecture on the topic, any number of graduate (and even some of the more geeky undergraduate) students could have done it, but the choice of Winnie was inspired because, instead of just telling these young things the dry facts and functions of the system — let’s face it, they can learn that from a book or even wikipedia.* But here’s a chance for them to learn how the system works in actual fact, from someone who has used it to screw others and been screwed himself, and to learn all that from someone who, just coincidentally, is in a position to demonstrate that no matter how down and out a politician might seem, under MMP he’s only one voter in twenty away from the marble floors, dark wood and green leather benches which house our democratic institutions.

The speech itself is the saga of the heroic battlers who guided the noble, fragile MMP system through the minefields of bureaucracy, persevering despite the “inner cabal cherishing hidden agendas” intent upon bringing about its premature demise. Those heroic battlers were represented by New Zealand First, epitomising the “traditional values of New Zealand politics”; “capitalism with a kind, responsible face”; the “long established social contract of caring for the young and the old and those who were down on their luck through no fault of their own”; a strong, honest party which was forced into coalition with National, although even then the dirty hacks in the media failed to correctly report these facts.

It’s a wonderful story, a fabulous creation myth, and if you’ve listened to Winston’s speeches over the years, none of it will be foreign to you.

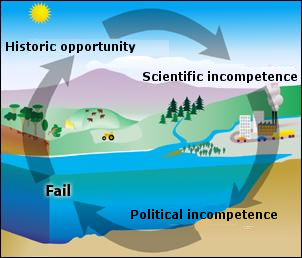

But the speech dwells upon the darker, more recent history of MMP, and particularly its perversion by the forces of separatism. This initially seems odd for a speech which praises MMP, but it makes perfect sense when you consider the wider narrative: you can’t rescue something which isn’t in trouble, and the wider narrative is, naturally enough, that Winston is here to rescue New Zealand from MMP and the separatists — blue and brown — who have overtaken it. This is done, in true Winstonian style, with a masterful play on words:

You’ve all heard or seen the British comedy TV show “the two Ronnies†– well we have our own comedy show starring the “two Honesâ€. Hone, of course, is Maori for John – and the two “Hones†don’t give a “Heke†about who they insult on Waitangi Day.

If you listen closely, you might almost be able to hear the sound of undergraduates giggling nervously, and more quietly but present nevertheless, the sound of confused and frustrated battlers who don’t see what they stand to gain out of any of the current political orthodoxy starting to think “you know, Winston wasn’t so bad after all.”

So, Winston is back. For the record, I still don’t think he’s got the winnings of an election in him without the endorsement of an existing player, and I think it’s better than even money that he would drag any endorser down with him. His credibility is shot to hell, and this is a naked attempt to reach out to a Labour party who have just begun to put a little historical distance between themselves and him, but it will be very tempting for a Labour party struggling to connect with the electorate. If we as a nation are very, very unfortunate, Labour’s failure to reinvent themselves and the illusory success among some of the usual suspects of the “blue collars, red necks” experiment last year — notably not repeated in this week’s speech — will cause them to reach out for the one thing they lack: a political leader who understands narrative, who possesses emotional intelligence and political cunning in spades, who knows how to let an audience know who he is and what he stands for, and make them trust him (sometimes despite all the facts), and who has a ready-made constituency of disgruntled battlers who feel (rightly or wrongly) that the system doesn’t work for them.

Please, let it not come to that.

L

* Incidentally, it may come as a surprise to some of you that these dry facts and procedural details were the reason I dropped out of PoliSci in my first year, and studied Film instead (before realising that it all came back to politics anyway).