In International relations, realism refers to the view that States have interests and use relative power capabilities to pursue those interests in an anarchic world order lacking a superordinate power or Leviathan (that is, a condition that Hobbes referred to as the “state of nature’). Conversely, idealism refers to the better angels and perfectibility of humankind, seeing a desire for cooperation as being equally as strong as the urge to enter into conflict with others. Constructivism tries to bridge the gap between realism and idealism by positing that the creation and expansion of international institutions designed to foster cooperation and diminish conflict is a means to constrain anarchy in world affairs. International systems analysis serves as a meta-theory that sees the world order in quasi-organic terms, as an evolving entity that is more than the sum of its aggregate parts and which has an unconscious logic and process of its own that is a collective response to the machinations of individual States and other non-State actors, thereby mirroring the invisible hand of the economic market when it comes to determining efficiency at a systemic level.

Classic realism dates back to Otto von Bismarck and has it most recent exponents in Henry Kissinger and John Mearsheimer. Idealism draws its inspiration from Woodrow Wilson, and constructivism owes its reputation to Alexander Wendt. International systems theory is the brainchild of Morton Kaplan. The works of these authors and others such as Hans Morgenthau and Kenneth Waltz continue to be the guideposts for current practitioners throughout the West (the list is illustrative only, as the number of authors involved in International relations theorising is great).

Realism posits that States have core and secondary interests; that threats are existential, imminent, or incidental; that States may have allies and enemies but do not have friends because interest, not affection is what defines their relationships; that wars are defensive or offensive in nature and are fought for existential and imminent reasons that can lead to pre-emptive strikes against existential and imminent threats as well as preventative attacks to reduce the possibility of an adversary reaching imminent threat status. Wars of opportunity are discouraged because they can lead to uncertain and unexpected outcomes and do not involve existential or imminent threats or core interests; wars of necessity are fought because they have to be, as they involve core interests and are fought against existential or imminent threats.

The current world moment has seen another development, one that is less salubrious in part because it originates from within authoritarian regimes like those governing Russia, the PRC, DPRK, Turkey, Iran and other contemporary dictatorships. The basic premise of this school of thought, which I will call “authoritarian realism” is that a new world order must be created that replaces the Western-centric liberal international order that has been present in world affairs for the last sixty or so years and which has dominated the landscape of international relations since the end of the Cold War. The latter is the system that we see in the form of the UN and other international organisations like the ILO, WTO, WHO, IMF, EU, OAS, OAU, PIF, SPC, NATO, SEATO, UNITAS, ASEAN, IADB, World Bank and a word salad of other regional and multilateral organisations.

For authoritarian realists, these organisations constitute an institutional straitjacket that constrains their freedom of manoeuvre on the global stage as well as that of most of what is now known as the “Global South:” post-colonial societies locked into subordinate positions as a consequence of Western imperialism and neo-imperialism. For authoritarian realists, the supposed ideals that liberal international institutions espouse and what they were constructed to pursue were done for and by Western colonial and neo-colonial powers seeking to establish an undisputed hierarchical status quo when it comes to how international affairs and foreign policy is conducted. More pointedly, in authoritarian realist eyes now is the time for that hierarchy to be challenged because the balance of power between the liberal democratic West and emerging non-Western contenders has shifted away from the former and towards the latter.

That is due to the fact that in the transitional period after the US lost its status as sole superpower “hegemon” in world affairs (stemming from 9/11, its ill-advised invasion of Iraq, long-term and futile engagement in Afghanistan and other conflict zones as well as it mounting internal divisions), the world has been moving to a new order in which other Great Powers compete for prominence, and in which the norms and rules-based liberal internationalist system has been replaced by norm erosion, norm violations and conflict on the part of uncooperative nation-States and non-State actors pursuing their goals outside of established institutional parameters.

This is, in other words, the state of nature or anarchy that Hobbes wrote about on which realists are most focused upon. Liberal rules and norms are no longer universally binding so the default option is to use national power capabilities to pursue individual and collective interests unfettered by self-binding adherence to dysfunctional and biased global institutions.

In realist views power is relative rather than absolute and covers a host of material and ideological dimensions–economic base, diplomatic acumen, military might, internal political and social stability and ideological consensus, and so forth. Adversaries must calibrate their responses to others based on their assessments of relative aggregate power vis a vis each other as well as other States and international actors. For authoritarian realists it is clear that the West is in decline on most power dimensions, especially morally, culturally and politically as exemplified by the US in the last decade. The West still has economic, military and diplomatic power, but the rise of the PRC, India (nominally democratic but increasingly authoritarian in practice), Russia, Turkey, Iran and lesser dictatorships, coupled with an rightwing authoritarian shift in places like Hungary, the US, Italy and France, demonstrates that the halcyon days of liberal democracy are now past. All talk of climate change, work-life balance, LBGTQ rights and indigenous voice notwithstanding, progressivism (either class-or identity-based) is not making significant gains on the world stage, at least in the eyes of realists in both the West as well as the South and East.

Most fundamentally, what separates the democratic and authoritarian realists is not power per se, but values. For authoritarian realists the liberal democratic West is in decline, overcome by its own excesses, degeneracy, corruption, inefficiencies, vacilliatory leaders and other affronts to the “natural” or “traditional” order of things. In contrast, modern authoritarians (including those in the West) value hierarchy, efficiency, unity of purpose, the demographic superiority of their dominant in-groups, decisive leadership and strength of resolve. Freedoms of speech, association and features such as judicial independence from political authority are seen by authoritarians as easily exploitable Achilles Heels through which division and disunity can be fomented in liberal democracies using disinformation, misinformation, graft and other influence campaigns. Liberal democrats are egalitarian “betas.” Authoritarian realists are self-identified “Alphas.” Consequently, the current word moment is seen as a window of opportunity for authoritarian realists to press their relative (Alpha) advantage in order to re-draw the global geopolitical map and its institutional superstructure. This redrawing project can be considered the authoritarian (neo) version of constructivism on the world stage.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Hamas attack on Israel are examples of how Russia practices authoritarian realism directly and indirectly. The idea in the first instance was to redraw the map of Europe via direct aggression on a former vassal state, assuming that NATO and the EU were too divided and weak after BREXIT and Trump when it came to a collective response. That would impede military support for Ukraine, thereby facilitating a Russian victory on Europe’s southeaster flank, something that would further divide and weaken European resolve to confront Russia, leading in turn to more Russian “assertiveness” along its Western Front. Although that assumption proved false and in fact has backfired at least for the moment, the original concept of exploiting perceived Western weakness was and is clearly at play given ongoing divisions within Western nations about if and how to continue supporting the Ukrainian military effort. The end game of that conflict has yet to be written and could well play into Russia’s favour if extended indefinitely until Western electorates tire of supporting governments that continue to direct resources towards someone else’s war.

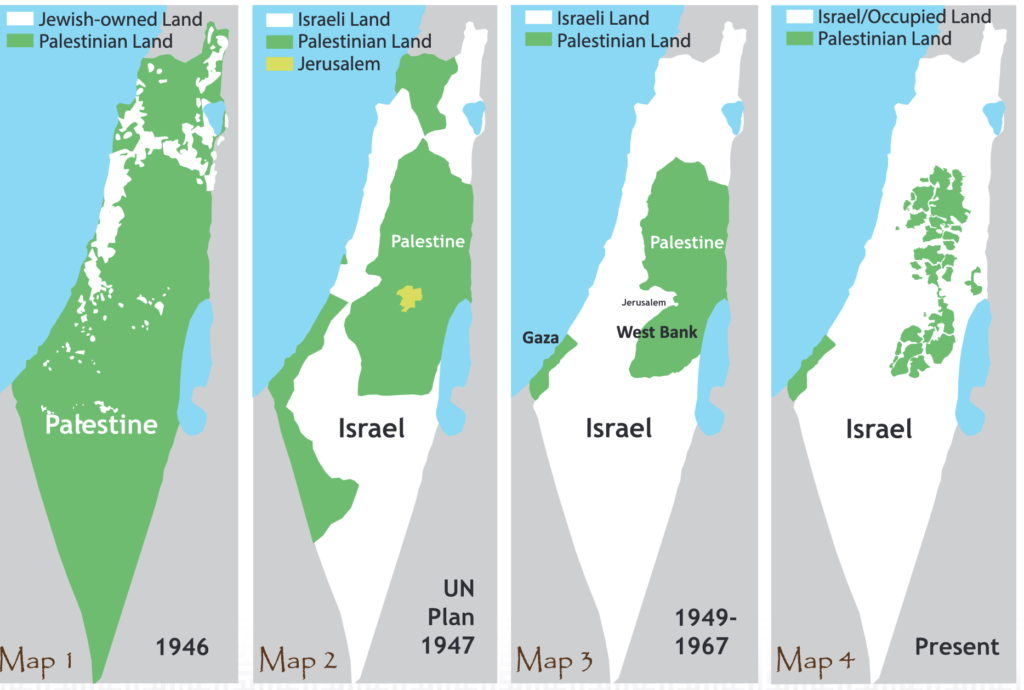

Hamas’s attack on Israel came after long-term planning, training and equipping involving its two major sponsors: Iran and Russia (who are military partners). Here the goal is to use the attack and the expected Israeli over-reaction (collective punishment of Gazan civilians for Hamas’s crimes) to sow discord within the Arab world and beyond. Although the official response from most Western governments and corporate media is (at times jingoistically) pro-Israel, pro-Palestinian demonstrations across the world have laid bare the broader social-political divisions aggregated around the conflict. Moreover, other than the US and UK, no major power is offering military support to Israel, and China and Russia have both condemned the Israeli response without mentioning Hamas in their pronouncements (and in fact are silent partners with Iran in supplying war materiel to Shiite militias like Hezbollah, Hamas, Houthis and the al-Sadr brigades in Iraq, even while both maintain strong economic ties to Israel). Although a NATO member and a quiet security partner of Israel’s, Turkey has been silent on the matter and allows Hamas to maintain a presence on its territory. Normally a strong supporter of Israel, India has gone very muted in its response to the violent tit-for-tat now taking place. It is as if authoritarian realists see the broader realignment taking shape before them and do not want to be caught off-side.

Sunni Arab governments such as those of Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which have worked to normalise relations with Israel, have now had to backtrack in the face of unrest emanating from the Arab street, and the prospects of the conflict expanding to several fronts in Southern Lebanon, the Golan Heights and West Bank and even spilling over into a major regional war involving Syria, Iran and their patrons cannot be discounted. All of which will help redefine the geopolitics of the Middle East as well as its relationship to extra-regional interlocutors regardless of the specific outcome of this latest iteration of what has become a perpetual war.

In the South and East China Seas, the Sino-Indian border and the borderlands of Tibet and Bhutan, the PRC has engaged in aggressive military diplomacy, using force to annex foreign territories and present a new territorial status quo to its neighbours. As with the Russian interventions in Georgia and Ukraine, these usurpations have been declared unlawful by international courts and condemned by international organisations like the UN. And yet, because of alack of enforcement power–and will–on the part of the International community as currently represented by its institutional edifice of regional bodies and international organisations, these moves have been only lightly challenged, gone largely unpunished and certainly have not been reversed. The result is a new status quo in East Asia in which PRC sovereignty is claimed and de facto accepted well to the West of its recognised interior land borders and far to the South of its littoral seas.

In the authoritarian realist mindset, moves to take advantage of the current moment in order to redraw the international geopolitical order, including its institutional foundations, are critical to their survival as independent powers. The PRC is driven by a desire to finally achieve its rightful place as a Great Power after centuries of humiliation by foreign powers. For Russia it is about re-claiming its place as an Empire. For lesser dictatorships it is about using national power to move unconstrained in the global arena, unencumbered by the protocols, norms and niceties of the liberal internationalist order. For all of these authoritarians, marshalling their resources in a common effort to undermine and replace Western institutions is a giant step towards real freedom of action in which relative power is the sole determinant of what a nation-State can and cannot do when it comes to foreign relations. If one is charitable, there might even be a bit of idealism attached to these various projects, as authoritarian realists use soft power applications in order to help the Global South out from under the yoke of Western post-colonial imperialism once and for all even as they empower themselves by doing so.

Some of this is evident in projects like the PRC Belt and Road Initiative, which is a global developmental project that is designed to challenge and replace Western developmental assistance and cement the PRC’s position as the foremost provider of infrastructure investment and financial aid to the Global South. In parallel, both Russia and China have expanded their military alliance networks in the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa while courting more engagement with Latin American and Central Asia countries (India and Pakistan, respectively). Russia and the PRC have quietly revived and assumed stewardship of the so-called BRICS bloc of nations, including expanding its membership to include Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE in 2024. On both economic and military fronts, authoritarian realists are constructing an alternative to the liberal international order.

All of this manoeuvring has added a new twist to the long transitional moment that the international system is undergoing and in fact has altered the way in which the emerging systemic realignment is being shaped. Rather than the anticipated move from a unipolar world dominated by the US to a multipolar world in which the US shared space as a Great Power with emerging and re-emerging Great Powers like the PRC, India, Russia, Japan and perhaps Brazil and/or others, what is coming into shape is a new bipolar world made up of competing constellations or networks of like-minded nation-States, to which are being added non-State technology actors looking for economic opportunity in increasingly loose regulatory environments brought about by the erosion of international rules and norms in the field of transnational commerce.

There is some time to go before the full shape of the new bipolar “constellation” order is confirmed. Authoritarian realists will retain their own nation-centric views even if their interests overlap in the bipolar constellation format. Western nations will need to revise their approaches to world affairs and in particular their positions vis a vis the post-colonial Global South given the competition for the South’s attention provided by the authoritarian realists. All of this makes for uncertain and fluid times in which the best hedge is multi-level power multiplication with focused application by the emerging constellations of competing States and associated non-State actors. How the wars in Ukraine and in Gaza turn out will give us a relatively short-term glimpse into what the geopolitical order will look like by the end of the decade because technology, will and multinational commitment are now being put to the test in both new and old ways in those arenas.

Two things are worth noting. At this critical juncture it is by no means assured which side of the emergent bipolar constellation balance of power will be favoured over the long term. What is certain is that only one side is actively working to re-make the world order in that image, Those are the authoritarian realists.