Although I am loathe to prognosticate on fluid situations and current events, I have been thinking about how the conflict in Iraq has been going. Although I do not believe that the Islamic State (IS) is anywhere close to being the global threat that it is portrayed to be in the West, I do believe that it is an existential threat to Syria, Iraq and perhaps some of their Sunni neighbours. Unlike al-Qaeda, which has limited territorial objectives, IS is political-religious movement with serious territorial ambitions that uses a mix of conventional and unconventional land warfare to achieve them. Given that difference, below is an assessment of the situation in Iraq after the fall of Ramadi into IS hands.

Iraq’s Anbar Province, a Sunni stronghold, is now under IS control. Tikrit was occupied a few months ago, Falluja and Haditha fell some weeks ago and Ramadi was conquered a week ago. To the northeast, Mosul remains in IS hands, while Baiji (site of major oil processing facilities) and Samarra remain under siege. With dozens of smaller towns in Anbar and elsewhere under IS rule, to include a front extending south-southeast from Tikrit to the eastern Baghdad suburbs along the Tigris River basin, the advance on the capital appears inevitable. Or is it? In this post I attempt to outline the strategic situation that the NZDF has thrust itself into.

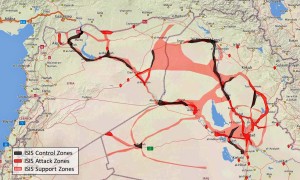

Map courtesy of the DailyMail Online (http://www.dailymail.co.uk).

Map courtesy of the DailyMail Online (http://www.dailymail.co.uk).

First, let’s look at the positives (from the West’s perspective). There is no way that IS can physically take and occupy Baghdad. A city of nearly four million people, most of them Shiia, Baghdad is a fortress when compared to what IS has tackled so far. It has concentrated military forces, is the seat of national government and is the location of numerous foreign military and diplomatic missions. It is therefore a strategic asset that Iran, the West and Iraqi Shiites cannot afford to lose. Moreover, IS is stretched too thin on the ground in Iraq to have the numbers to engage effective urban warfare against a determined and concentrated enemy, has no air power and does not have enough Sunni support in Baghdad to make up for the lack of numbers on the ground (A digression here: IS has a Salafist ideology buttressed by Ba’athist political and military organisation. Much of its leadership is drawn from the ranks of displaced Sunni Ba’athist officials in the Saddam Hussein regime, and it enjoys considerable support in Sunni Iraq. This accounts in significant measure for its success in Anbar).

Although not located in Anbar, Mosul, Samarra and Tikrit also have Sunni majorities, so the trend has been for IS to target and conquer urban areas where its sectarian support is matched by demographic numbers. The question remains as to whether its military campaign can be equally successful in Shiia dominant areas to the east and south of Baghdad, where Iranian forces also have a presence. That appears unlikely.

On the negative side from the West’s perspective, IS appears to be engaging in a pincer movement designed to surround and isolate western and northern Baghdad from the rest of the country. If it able to control the land routes in those areas it can cut off not only supply lines between Baghdad and its allied forces in the north and west, including Camp Taji where the NZDF is supposed to be stationed (I say supposedly because I have read an unconfirmed report that the NZDF deployment are stuck in Baghdad because of the increase in IS hostilities), but it can also proceed to apply a chokehold on supplies entering Baghdad via the north and west. As part of this strategy IS will target the power grid that supplies Baghdad, the majority of which comes from its north (including the power plant at Baiji, now under siege) as well as water supplies drawn from reservoirs in the northwest and piped to Baghdad. This will not be fatal if the Baghdad government can keep its land lines of supply in the south and east open, but it certainly will hinder its ability to keep some (more than likely Sunni) neighbourhoods stocked with life essentials, which will only exacerbate their alienation from central authorities and perhaps contribute to their support for IS.

Moreover, if more difficult to achieve, IS does not need to control all of the territory to the east and south of Baghdad in order to choke it off. All it has to do is establish a thin mobile front that can gain and hold intercept points on the major highways surrounding the city (and relatively close to the city limits at that, which obviates the need to fight Shiias further afield). This includes targeting power and water supplies coming from the south and east.

In other words, IS does not have to achieve strategic depth in order to choke the arterial routes leading into the city from the south and east. Coalition airpower may be able to stave off this eventuality for a while but without ground control that allows unimpeded re-supply, Baghdad will be operating on a scarcity regime within a few months. Resupply by air, while significant, cannot substitute for land supply, and it is worth noting that Baghdad airport as well as the infamous Abu Ghraib prison (where many Sunni militants are held) lie west of Baghdad and have recently been the subject of IS attacks. In fact, in the last year both Abu Ghraib and the prison at Taji have been the scenes of major prisoner jailbreaks orchestrated by IS, with many of the escapees now thought to have joined its ranks in an effort to increase its knowledge of the local fighting terrain.

A microcosmic version of this scenario involves the city of Taji, location of Camp Taji, the huge military base that is the destination point for the NZDF contribution to the anti-IS coalition. Straddling national highway one 20 miles northwest of Baghdad west of the Tigris river, Taji is the last significant town on the run south into Baghdad. With the old Saddam-era and later US military base capable of housing a mix of 40,000 Iraqi and foreign troops (although in reality there are far less on base), and home to a 1700 meter runway and Iraqi’s armoured corps, it is now the focal point of foreign training of Iraqi troops. As such and because of its location, it is a major target for IS, which controls the territory immediately east of the Tigris (about 11 miles away from the base). Since Taji is only 30 miles from Falluja, the presumption is that IS will mass it’s force to the east, west and north of Taji, then launch offensives designed to gain control of the town and highway. That would leave the base cut off from land routes and force it to rely on air re-supply and/or fight its way out of containment. If that happens it is doubtful that the NZDF troops will hunker down “behind the wire” and do nothing else. Whatever the scenario, isolating Camp Taji from Baghdad is a primary IS objective in the next months and will be essential to any move to surround and squeeze the capital city. The good news, from the West’s perspective, is that in order to isolate the base and sever its land link to Baghdad, IS will have to mass significant numbers of fighters, artillery and armour, something that makes it vulnerable to coalition air strikes.

The bottom line is that a successful pincer movement will slowly strangle and starve Baghdad, something that it turn will force the Iraq government to seek a political settlement on terms favourable to IS. That will entail the ejection of foreign forces and partition of Iraq. IS will claim Sunni-dominant areas and merge them with the territory it holds in Syria (IS controls roughly half of Syria’s territory) to establish its caliphate. It has no real interest in Iraqi Kurdistan because it cannot defeat the Peshmerga and other than the oil facilities on its western flank, Kurdistan has no strategic assets. Likewise, Shiia dominant areas of Iraq are too large and populated for IS to occupy, plus any incursion into Iraqi Shiia border territory with Iran will invite a military response from the latter. But where IS is in control, it has already begun to provide the basic services that the Iraq and Syrian governments no longer can, which raises the possibility that partition is already a fait acompli. As stated in The Economist:

“The danger is that the IS caliphate is becoming a permanent part of the region. The frontiers will shift in the coming months. But with the Kurds governing themselves in the north-east, and the Shias in the south, Iraqis question the government’s resolve in reversing IS’s hold on the Sunni north-west. “Partition is already a reality,†sighs a Sunni politician in exile. “It just has yet to be mapped.†(“The caliphate strikes back,” The Economist, May 23. 2015 (http://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21651762-fall-ramadi-shows-islamic-state-still-business-caliphate-strikes-back, May 23, 2015).

Thanks to the Iraqi Army abandoning their positions and leaving their equipment behind, IS has captured significant amounts of modern US made weaponry, including the equivalent of several armoured columns. It now has anti-aircraft munitions that eventually will score hits on coalition aircraft. Its fighters are a mix of seasoned veterans and unprofessional jihadis, but IS field commanders have been judicious in their use of each (for example, employing  inexperienced foreign jihadists in first wave assaults or in suicide bombings using construction vehicles to breach enemy lines, followed by artillery fire and hardened ground forces). What that means is that IS has the realistic ability to cut off Baghdad’s land access to its near north and west, which will force the Iraq military and coalition partners to stage a counteroffensive to reclaim those lines of supply.

IS relies on mobility, manoeuvre and the selective application of mass force to achieve it ends. The fall of Ramadi was accomplished by rapidly surrounding it from the north and east and focusing firepower on one garrison in it. IS also has relatively unencumbered supply lines coming from Syria, and many suspect that supplies also come from Saudi Arabia and Turkey (Iraq has land borders with those states as well as Iran, Jordan and Kuwait. There is a strong belief–which could well be confirmed by the document retrieval made during the US Special Forces raid on a senior IS financier’s hideout in Syria– that the Saudis in particular are doing more than just financing IS as a hedge against Iran). The best check against its advances is demographic density in Shiia dominant parts of the country and the fact that any adventurous move in the east or south will be met by serious Shiia militia and Iranian military resistance (Sadr City, a bastion of Shiia militias, lies on the northeast of Baghdad and Basra, a major oil refining centre and home of the so-called (Shiia) marsh Arabs, is the capital of the south).

Source: Institute for the Study of War, September 26, 2014.

For those who believe that coalition air power is enough to stem the tide of IS advances, let me simply point out that history has shown that air power alone cannot determine success in a territorial conflict, especially an irregular or unconventional one. Vietnam is a case in point. In the battle for Ramadi the coalition conducted 275 air strikes and still saw the city fall to IS in the space of days. Thousands of coalition air strikes have been launched against IS and while they slowed down many IS advances and were decisive in battles between Kurdish peshmurga and ISIS forces in Syria and northeastern Iraq, they have not proven so when the forces they are supporting are too few or lack the will to fight when things get ugly. Since IS prefers to move quickly between urban areas and stage assaults from within them, the fear of civilian casualties hampers the coalition’s ability strike surgically at them in urban settings. That leaves the coalition with the task of trying to target IS convoys and garrisons, something that has proven hard to do given the dispersed nature of their campaign outside of urban areas.

It would seem that the best way to counter IS advances is to pre-emptively launch counter-offensives using a mix of foreign and Iraq troops and militias. That involves accepting Iranian military participation in concert with Western forces and requires moving sooner rather than later to at least stall IS’s progress southward. But if we take standard basic training as a guideline, then the Iraqi Army forces that have begun to be trained by the coalition troops will not be ready to fight until mid July. That may be too late to stop IS before it reaches Taji and the western Baghdad suburbs. Thus the conundrum faced by the coalition is to commit group troops and accept Iranian military help now or wait and hope that IS will slow down its advance due to its own requirements, thereby allowing training provided to the Iraqi Army by foreigners like the NZDF enough time to strengthen it to the point that it can take back the fight to IS with only marginal foreign assistance.

At worst, the latter is a pipe dream. At best, it is a very big ask.