The CV-19 (COVID) pandemic has seen the imposition of a government ordered national quarantine and the promulgation of a series of measures designed to spread the burden of pain and soften the economic blow on the most strategically important and most vulnerable sectors of society. The national narrative is framed as a public health versus economic well-being argument, with the logic of infectious disease experts being that we need to accept short term pain in the form of social deprivation and loss of income in order to achieve long term societal gain once the infection has run it course. However, some business leaders argue that a prolonged shut-down of the productive apparatus will cause irreparable harm to the national economy out of proportion to the health risks posed by the pandemic, and thereby set back the country’s development by twenty years or more.

The lockdown is a classic test of the age old philosophical question behind the notion of the “tragedy of the commons:” Should we pursue the collective good by accepting self-sacrifice in the face of an invisible threat and uncertain common pay-off, or do we pursue immediate self-interest and opportunism rather than accept material and lifestyle losses amid the same uncertainties and invisible rewards? Needless to say, it is not a straight dichotomy of choice, but the poles of the dilemma are clear.

Another thing to consider is a principle that will have to be invoked if the disease spreads beyond the ability of the national health system to handle it by exceeding bed and ventilator capacity as well as the required amount of medical personnel due to CV-19 related attrition: lifeboat ethics. If the pandemic surpasses that threshold, then life and death decisions will have to be made using a triage system. Who lives and who dies will then become a public policy as well as moral-ethical issue, and it is doubtful that either government officials or medical professionals want to be placed in a position of deciding who gets pitched out of the boat. So, in a very real sense, the decisions made with regard to the tragedy of the commons have serious follow up effects on society as a whole.

One thing that has not been mentioned too much in discussions about the pandemic and the responses to it is the serious strain that it is placing on civil society. Much is said about “resilience” and being nice to each other in these times of “social distancing” (again, a misnomer given that it is a physical distancing of individuals in pursuit of a common social good). But there are enough instances of hoarding, price-gouging, profiteering–including by major supermarket chains–and selfish lifestyle behaviour to question whether the horizontal solidarity bonds that are considered to be the fabric of democratic civil society are in fact as strongly woven as was once assumed.

There is also the impact of thirty years of market economics on the social division of labour that is the structural foundation of civil society. Along with the mass entrance of women into the workforce came the need for nanny, baby-sitter and daycare networks, some of which were corporatised but many of which were not. Many of these have been disrupted by the self-isolation edict, to which can be added the shuttering of social and sports clubs, arts and reading societies, political and cultural organisations and most all other forms of voluntary social organisation. Critical services that rely on volunteers remain so rural fire parties, search and rescue teams, the coastguard and some surf lifesaving clubs are allowed to respond to callouts and maintain training standards. But by and large the major seams of civil society have been pulled apart by the lockdown order.

This is not intentional. The government wants the public to resume normal activities once the all clear is given. It simply does not know when that may be and it simply cannot spend resources on sustaining much of civil society’s infrastructure when there are more pressing concerns in play. The question is whether civil society in NZ and other liberal democracies is self-reproducing under conditions of temporary yet medium-termed isolation. The Italians hold concerts from their balconies, the Brazilians bang pots in protest against their demagogic populist leader, Argentines serenade medical and emergency workers from rooftops and windows. There is a range of solidarity gestures being expressed throughout the world but the deeper issue is whether, beneath the surface solidarity, civil society can survive under the strain of social atomisation.

I use the last term very guardedly. The reason is because during the state terror experiments to which I was exposed in Latin America, the goal of the terrorist state was to atomise the collective subject, reducing people to self-isolating, inwards-looking individuals who stripped themselves of their horizontal social bonds and collective identities in order to reduce the chances that they became victims of the terrorists in uniforms and grey suits. The operative term was “no te metas” (do not get involved), and it became a characteristic of society during those times. At its peak, this led to what the political scientist Guillermo O’Donnell labeled the “infantilisation” of society, whereby atomised and subjugated individuals lived with very real fears and nightmares in circumstances that were beyond their control. Their retreat into isolation was a defence against the evil that surrounded them. Today, the threat may not be evil but it is real and pervasive, as is the turn towards isolation.

I am not suggesting that there is any strong parallel between state terrorism in Latin America and the lockdown impositions of democratic governments in the present age. The motivations of the former were punitive, disciplinary and murderous. The motivations of the latter are protective and prophylactic.

What I am saying, however, is that the consequences for civil society may be roughly comparable. Many Latin American societies took years to reconstitute civil society networks after the dictatorial interludes, although it is clear that, at least when compared to advanced liberal democracies, the strength of democratic norms and values was relatively weak in pretty much all of them with the exception of Uruguay and Costa Rica. Yet, in places like NZ, democratic norms and values have been steadily eroded over the last thirty years, particularly in their collective, horizontal dimension.

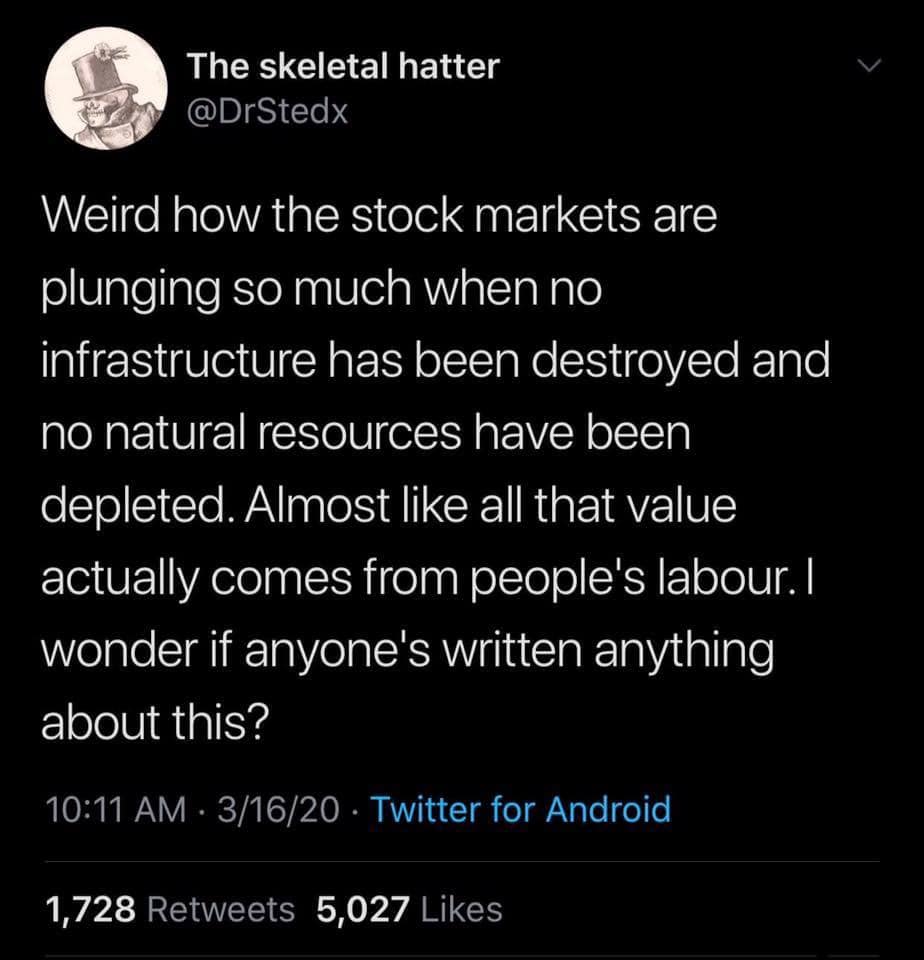

The reason is ideological: after three decades of imposed transmission, market-driven logics vulgarly lumped together as “neoliberalism” are now a dominant normative as well as structural trait in NZ society. The country has many, if not more hyper-individualistic self-interested maximisers of opportunities in the population as it does those with a commonweal solidarity orientation. Lumpenproletarians populate both the socioeconomic elite as much as they do the subaltern, marginalised classes. Greed is seen by many as a virtue, not a vice, and empathy is seen as a weakness rather than a strength.

The ideological strength of the market-oriented outlook is seen in business responses to the pandemic. In NZ many want bailouts from a government that they otherwise despise. Many are attempting to opportunistically gain from shortages and desperation, in what has become known as “disaster capitalism.” Some try to cheat workers out of their government-provided wage relief allowances, while others simply show staff the door. Arguments about keeping the economy afloat with State subsides compete with arguments about infectious disease spread even though objectively the situation at hand is first a public health problem and secondly a private financial concern.

The importance of civil society for democracy is outlined by another political scientist, Robert Putnam, in a 2000 book titled “Bowling Alone.” In it he uses the loss of civic virtue in the US (in the 1990s) as a negative example of why civil society provides the substantive underpinning of the political-institutional superstructure of liberal democracies. Putnam argues that decreases in membership in voluntary societies, community associations , fraternal organisations, etc. is directly related to lower voter turnouts, public apathy, political disenchantment and increased alienation and anomaly in society. This loss of what he calls “social capital” is also more a product of the hyper-individualisation of leisure pursuits via television, the internet (before smart phones!) and “virtual reality helmets” (gaming) rather than demographic changes such as suburbanisation, casualisation of work, extension of working hours and the general constraints on “disposable” time that would be otherwise given to civic activities as a result of all of the above.

The danger posed by the loss of social capital and civic virtue is that it removes the rich tapestry of community norms, more and practices that provide the social foundation of democratic governance. Absent a robust civil society as a sounding board and feedback mechanism that checks politician’s baser impulses, democratic governance begins to incrementally “harden” towards authoritarianism driven by technocratic solutions to efficiency- rather than equality-based objectives.

The current government appears to be aware of this and has incrementally tried to recover some of the empathy and solidarity in NZ society with its focus on well-being as a policy and social objective. But it could not have foreseen what the pandemic would require in terms of response, especially not the disruptive impact of self-isolation on the fabric of civil society.

It is here where the test of civil society takes place. Either it is self-reproducing as an ideological construct based on norms and values rooted in collective empathy and solidarity, or it will wither and die as a material construct without that ideological underpinning. When confronting this test, the question for NZ and other liberal democracies is simple: is civil society truly the core of the social order or is it a hollow shell?

Given the divided responses to this particular tragedy of the commons, it is hard for me to tell.