A while back I was talking to a friend about the reasons why I believe that the US has failed so miserably in managing the Covid-19 pandemic. Our starting point was the idiocy surround the “masks interfere with our freedom” argument. Besides the fact that with individual and collective rights come responsibilities resulting in all sort of public interest regulations that people routinely accept (seatbelts, bike helmets for children, protective gear in the workplace), or the fact that retail outlets and other private entities routinely demand dress standards (“no shoes, no shirts, no service”), the problem appears to be rooted in the dumbing down of the US public over decades coupled with the rise of alternative (often false and conspiratorial) sources of information. As some have mentioned, never before have we had so much information at our finger tips and yet never before have we been so ill-informed.

That means that it is not political polarisation per se or leadership incompetence in the Oval Office that conspired to impede effective public health crisis mitigation. To be sure, once the narrative–encouraged from the White House–became one of “freedom” and “choice” versus THE STATE, the debate about pandemic control was hopelessly lost to the nutters. Rightwing media pushing the “freedom” versus authoritarianism line made things worse. But beyond that, the deep-seated mistrust of government, scientific expertise, health authorities and collective good sense in the US is rooted in something far more pernicious than the MAGA Moron phenomenon.

That something is the the erosion and corruption of what I will broadly describe as “social institutions.” These are the civil and political society groups that, along with their distinctive cultural and ethical mores and norms, are considered to be the foundation of collective identity and, writ large, notions of nationhood. In 2000 Robert Putnam ascribed the hollowing out of American democracy to the loss of these institutions in his book Bowling Alone, where he uses the metaphor of the post-1950s decline of bowling (and bowling alleys) as evidence that US civil society, and along with it civic virtue, was/is in decline. He called this a loss of “social capital.” It is the loss of social capital that is the root cause of today’s US predicament.

I am aware of the many good critiques of Putnam’s book and so will just address and add to the notion that a decline in social institutions is a precursor to the type of political polarisation and social anomaly that exists in the US today.

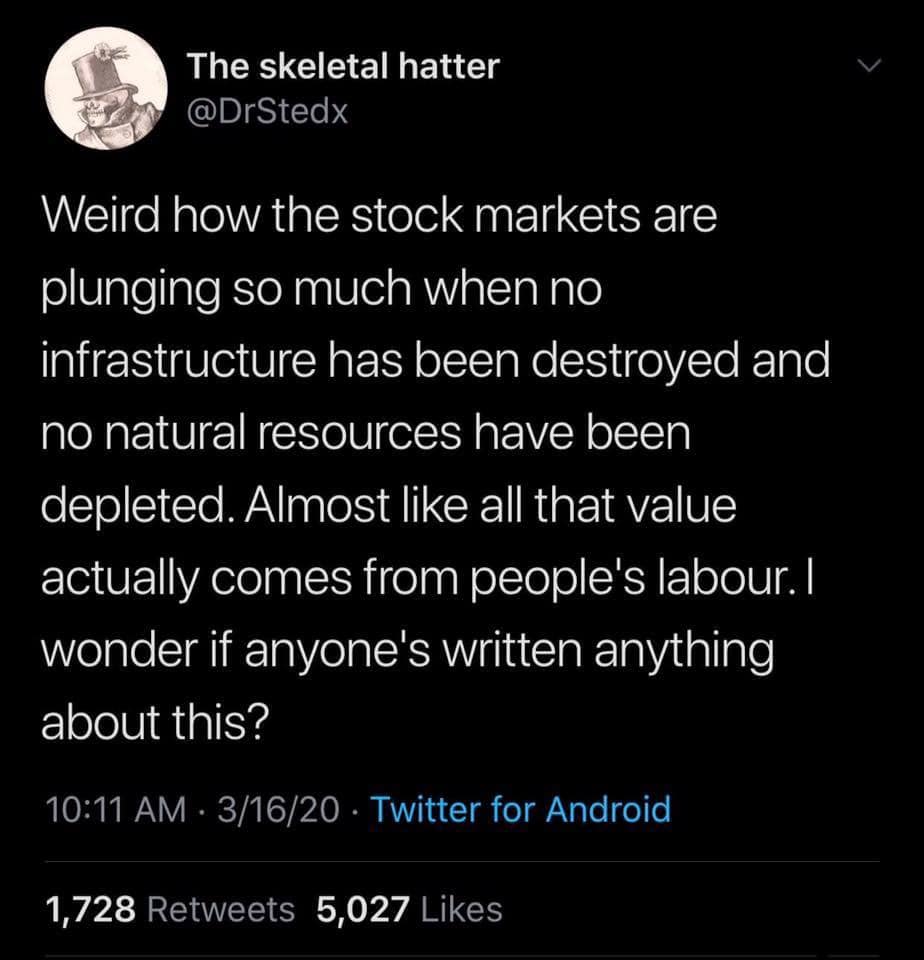

First of all, Putnam did not adequately explain the relationship between the decline of “social capital” and the evolution of US capitalism over the last half century. The move from postwar industrial logics of production to increasingly service-oriented economics amid a technology-propelled globalisation of commerce and exchange was the main driver in the entrance of women into the commodified labor force amid the destruction of the industrial era social division of labor. Unions declined, part-time work became mainstreamed, two-income families became a necessity rather than a choice, automation and out-sourcing killed off entire industries, corporate savings declined while “leveraged” borrowing and debt increased –the list of changes is long. The US is now a military-industrial, high tech, highly automated service-oriented economy, and the strong industrial class lines that emerged before and after WW2 have now been broken into a small but unified class elite governing over dozens of post-industrial class factions divided by race, region, religion and (types of) recreation.

Income inequalities have increased exponentially since 1980. The US is now a country where the top one percent of income earners own 30 percent of the country’s wealth, more than the entire middle class. The dislocating effects of the economic shifts of the last half century are both broad and deep, extending from corporate cultures, small business practices to inter-personal affective relationships.

To that can be added the alienating effects of advanced telecommunications, particularly the introduction of mass computing technologies that obliterated the barriers between personal, private, public and corporate communications, entertainment and consumption. Take the notion of leisure. What used to be collective pursuits held in public group settings, such as bowling, gradually were replaced by more individualised pursuits done in private settings, like gaming. Profits from physical attendance at sporting or entertainment events have been eclipsed by those generated by televised coverage of the events. Plus, with wages increasingly compressed (again, the reasons are many) and work demands increased, people no longer had the time or money to commit to social networking significantly outside of work-related activities.

Here is a small example. After World War Two my father worked at the General Motors Overseas Corporation (GMOC) based in New York. GMOC was the international production and trading arm of General Motors Corporation based in Detroit. For legal and tax reasons it was a separate business entity from the domestic side of the business, with its top management holding selected senior positions in the overall umbrella structure of the Detroit-based firm.

Back in those days my father was no senior manager. Instead he started as a mailroom clerk and worked his way up. He met my mother, a secretary, at GMOC. During the entire time that he was at GMOC, before he took a job in Argentina and GMOC New York was dismantled and integrated into the Detroit parent company, he played sports for GMOC teams. Baseball in the summer, basketball in the fall and winter, softball in the spring and bowling year round. He and my mom met in Central Park where the outdoor games were held and either had picnics or went out to eat after the games were finished. In colder weather they met in gyms and at the lanes to do variations of the same. When I was very young I was brought along to share those moments along with my parent’s colleagues and young families.

After we moved to Argentina my Dad continued to play softball for a GM team that was established there. It played against other automobile and oil companies (Ford, Chysler, Esso and Shell) and some local Argentine teams keen on improving their skills against US competition. Meanwhile, even before GMOC was reorganised and relocated to Detroit in 1971, the corporate athletic leagues in New York City began to decline as per Putnam’s observation. Younger employees moved to the suburbs rather than live in the buroughs, family pressures and commuting infringed on the time available to play ball, and by the end of the 1970s the entire network of NY corporate sports associations was on life support.

There have been attempts to resurrect or replace these Leagues with mixed success. The point is that their decline was driven not by changes in cultural mores alone but by the irresistible forces operating in production and in the social division of labour that grew out of them.

Even so, cultural mores have been at play in the decline of social capital in the US. The hyper-competitive drive that pushed the evolution of US capitalism has resulted in the emergence of what I think of as a “survivalist alienation” ethos coupled with a liability mentality. People increasingly see each other as competitors rather than colleagues, much less comrades. They abdicate personal responsibility in favour of “other-blaming.” An entire industry–personal injury litigation, aka ambulance chasing–has been built on these twin pillars. This leads to a form of collective narcissism that one might call “hyper-individualism:” it is all about me, me me.

This turn to the self is cloaked in a vulgarisation of social discourse evident in pop culture but extending much beyond it. Even sports have coarsened: cage fighting and scripted wrestling have moved from the fringe to the centre of profit-making athletics.

The impact is seen in what is left of social institutions. The phenomena of raging soccer moms and fighting baseball dads are so common that sports field security for pre-teens is required for insurance purposes and sideline rage has entire social media channels dedicated to it. Little kids now preen and strut, mock their opponents, and generally behave like the lumpenproletarians they see in professional sports. What this amounts to is a rot from within, where the pure soul of sport is carved out and replaced by something far darker.

Likewise, be it in bridge clubs or local volunteer fire departments, the US has seen both declining numbers and declining civility within social institutions. That is the social capital that is being lost. Horizontal solidarities have consequently been disrupted while vertical socio-economic disparities have increased. People are atomised in production and increasingly isolated in civil society. That leads to political alienation and dysfunction, making the terrain, as Gramsci said, “delicate and dangerous” and ripe for “charismatic men of destiny” to stamp their imprint on it. Trump and his GOP minions have done exactly that.

It occurs to me that the dislocating effects of capitalist production in its post-industrial phase coupled with a coarsening of popular discourse in the US lie at the root of the decline in social institutions/social capital that Putnam described, which in turn facilitated political polarisation, media stratification and a retreat into comfortable idiocy on the part of many citizens. That prevented any united approach to pandemic mitigation because the atomising and centrifugal forces at play were (and still are) multiple, overlapped, intertwined–and antagonistically reinforcing around the lightening rod that is the 45th president.

To this can be added two other American pathologies: lack of historical memory and the cultural predisposition towards the “quick fix” rather than more long-term, drawn out and measured responses. The lack of historical memory is not just about the 1918 so-called “Spanish Flu.” It is about any disease, from polio to SARS. Very little in the Trump administration, city or state responses was grounded in historical reads of previous disease eradication efforts (what references were made had mostly to do with case and death statistics, not to the progression of and specific mitigation efforts against the disease). Instead, when not a complete shambles of denial and blame-shifting such as that of the White House, what passed for containment policies were drawn from contemporary experiences around the globe. Even successful Obama-era public health campaigns were derided on partisan grounds. That might not have been problematic in places where the response initially worked, but given that Covid-19 has moved into second- and third-wave mutations, it was no panacea over the longer term.

This wilful lack of historical references is compounded by the American penchant for the “quick fix.” Rather than put on masks, practice social distancing and suffer short term economic deprivation for longer term gain, many Americans preferred to live their lives as usual, without precautions, bleating about their “rights” and “freedom” while they waited for a vaccine to be developed. Here too the lack of historical memory hurt, because many simply did not believe the experts when they said that, based on experience, a vaccine was a year or more away from being developed. As it turns out, vaccines have been developed and rolled out in less than a year, which is truly remarkable. But the disease moved deeper into society as winter came, and now 1 in very 1000 Americans (335,000) have died of it before the vaccine is broadly available. Cases are nearing 20 million and by the time the vaccine is widely available the estimates are that at least 10 million more will be infected and 400,000 American will be dead. Not surprisingly, both the prevalence of the disease and access to vaccines is marshalled along socio-economic class and ethnic lines.

In sum, the wretched excuse of the US pandemic response is the culmination of a long period of decline that is founded on the erosion of social institutions and loss of social capital caused by the evolution of the US mode of production. To be sure there are other intervening variables and factors at play in the cultural and political milieus that contributed to the disaster (because that is what this is–a human disaster in both cause and response). But in the end the problem of the US pandemic response was not one of public health failures but one of US capitalism and its social and political superstructure.

Hence the need during this holiday season for Americans to mask alone.