Years ago the Argentine sociologist Carlos Weisman wrote a book titled “Living within our Means.” It was a critique of Argentine society that focused on the paradoxical question of why, in a land of plenty, there was so much economic instability, inequality, corruption and political turmoil. His conclusion was basically that natural wealth produced indolence and greed: the vast natural resources in Argentina could be exploited inefficiently and without regard to the future, money was siphoned off of productive sectors into all sorts of nonproductive or money wasting enterprises ill-suited for the economics and demographics of the country, and the surpluses generated by the productive sectors (agriculture and mining in particular) could not only line the pockets of those lucky enough to control the means of production but could also be used to buy off subordinate group consent via State benefit distribution derived from minimal taxation on the export-oriented sectors that generated the bulk of the countries GDP.

His most important observation was that Argentines, so accustomed to an economic system that generated wealth in spite of itself, were living beyond their means. The State sector grew bloated, workers lost sight of the connection between productivity and wages, capitalists hoarded, spent and perfected the arts of tax dodging and capital flight, and politicians used patronage and public goods as a means of currying electoral favour, only to have the military step in from time to time under the pretence of putting things right but in reality only to shift benefits of political control to their civilian allies.

New Zealand is not quite as pathological, but for some time I have seen parallels with Argentina in that it appears that the country has, for at least two decades, been living beyond its means. Think of the so-called export sector.

Traditionally, “export sector” means those business that sell their goods overseas, to foreign clients. In NZ that historically meant agriculture (including cattle and sheep farming) mining, forestry and fishing. More recently, high tech value-added industries like software development have been layered into the export mix. But so too have industries like tourism and foreign language and tertiary education. Yes, tourism and educational services for foreign students are classified as “exports” in NZ even though all of the revenue generated and GDP share provided by these services are domestic in nature. Unlike traditional exports, other than some transportation companies, none of the economic activity associated with either industry is generated from abroad (say, via the sale of goods).

There is something insidious about this. Thriving in a largely unregulated environment, tourism surged. Adventure tourism, adrenaline tourism, hobbit tourism, backpacker and freedom camper tourism, glamour tourism, death tourism (trophy hunting) etc. all exploded even thought the infrastructure required to handle them was insufficient or non-existent. Likewise, dodgy fly by night language schools popped up catering to foreign students as young as high school age, and universities lowered admission standards and course requirements in order to attract unqualified foreigners who were willing to pay enrolment fees up to five times higher than domestic students. It did not matter that these foreign student often wound up as the victims of unscrupulous education “brokers,” local employers, hosts and homestay providers. That was fine because the business owners and senior managers operating these industries were rewarded handsomely for their efforts even if their contributions were not, to be clear, really advancing the productivity of NZ society. Both of these industries saw the foreigner’s dollar as their cash cow and soon became dependent on it. So long as the State got its share of tax revenues, all was hunky dorey as far as the economic-political elite was concerned.

A clear case of a non-traditional “export” that does more harm than good is the cruise line business. These floating Petri dishes used to be pretty scarce in NZ ports but now are now commonplace eyesores from the Bay of Islands to Akaroa and Milford Sound. They are seagoing pollution generators with dodgy labour and hygiene practices that disgorge thousands of clueless leisure lovers onto our shores to watch hokey “cultural” shows, go sight-seeing (including to active volcanoes) on fossil fuel vehicles and buy trinkets and baubles from money-grubbing vendors who otherwise could and should be providing services to their communities. What domestic benefit is derived from them is surprisingly narrow in scope, and yet they continue to come in increasing numbers–at least until CV-19 revealed them for what they are when it comes to public health risks.

Even traditional sectors like fisheries and dairy have come to rely more on export markets than on domestic consumption for their well-being, pushing unsustainable growth, environmental degradation, species destruction and oligopolistic market concentration. Uncoupling commodity pricing from domestic wage levels, some agricultural staples have been priced out of the range of most local consumers while a greater percentage of quotas and production are oriented towards foreign buyers. The situation has become so unbalanced in some sectors that, for example, given a drop in Asian demands due to the CV-19 pandemic, fishermen find it more economical to dump crayfish back into the ocean than sell them in the domestic market. Asian demand for cut wood has dried up, leaving huge surpluses in holding lots that are not being released into the domestic market. The price of many wage goods, consumer non-durables and staples is now set by international markets rather than by local demand, thereby narrowing the range of basic goods purchasable by the average NZ consumer.

In light of this, we might see the arrival of the Coronavirus (CV-19) as a great corrective on the national excess. The first industries to shut down are the ones that really should not have grown so large in the first place: tourism and tertiary education. These have been readily followed by service sectors associated with tourism and foreign students, including accomodation and food service provision.

Now the entire country is poised to “shelter in place.” With the government ordering mandatory closures and shut downs as it ramps up its response, primary and secondary schools have closed and a multitude of service providers have switched to at-home work or temporary closures. Soon a full scale lockdown will be imposed.

Essential industries and core state services continue to operate–transportation, food provision, emergency services, law enforcement, telecommunications, waste disposal, etc. Note that if we strip out the non-essential industries that are now shuttered or curtailed, we have a much smaller overall economic footprint yet a larger State presence within it. That is not necessarily a bad thing.

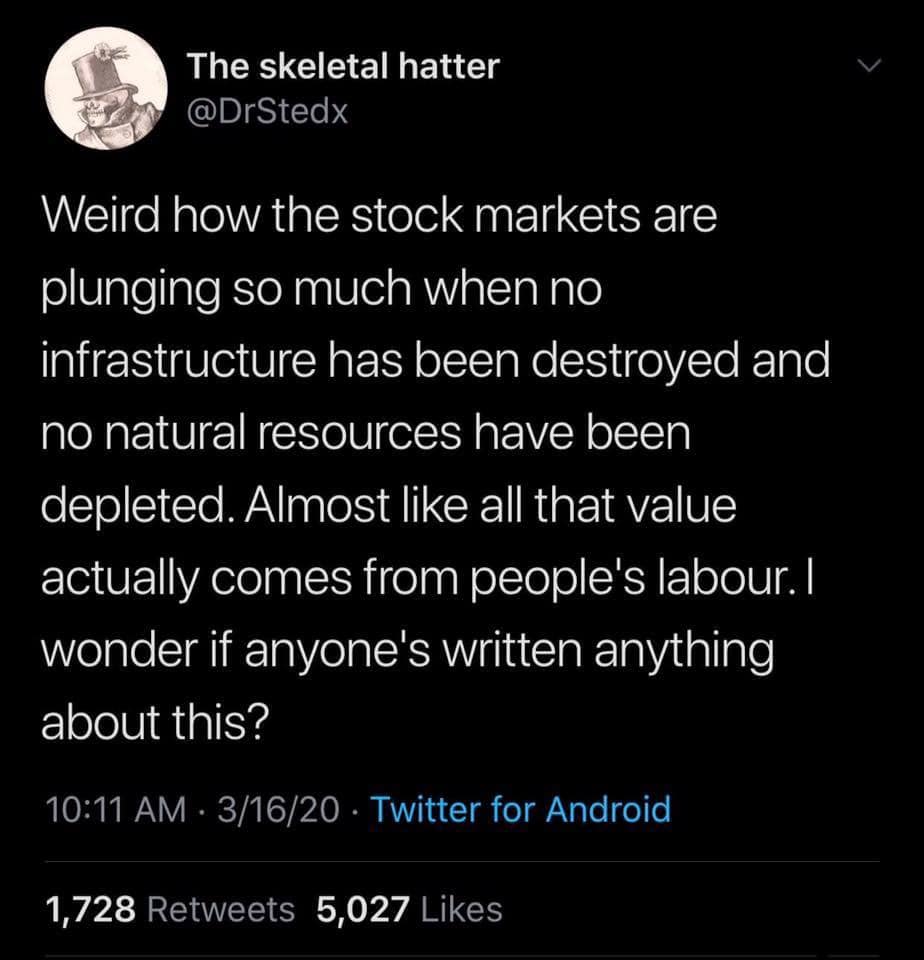

After years of market-driven logics that among other things pushed the kind of excesses described herein, the State is reassuming its role as macro-manager of the economy and direct provider of public goods and strategic production. Prudent financial management that protected surpluses “for a rainy day” allow the current government to ease the burden of pain inflicted on the working population by CV-19. It can also provide the material basis of an economic re-ordering on grand scale. One can only hope that, thanks to the pandemic, the era of down-sizing and privatisation has been proven to be a false promise when it came to national well-being and prosperity, and that it is replaced with a new economic logic that emphasises the importance of the social relations of production as much as the relations in and control of production itself.

There is one more component to this smaller, “natural” economic footprint: small businesses. The NZ economy runs on small business production and services. From metal working shops to plastics manufacturers, furniture makers and tradespeople, NZ has a middle sector in between the big agro-export corporates and State Owned Enterprises and private-public partnerships. The difference between them and the bloated tourism and tertiary education sectors is that they actually produce things of tangible value that benefit domestic society, not the degree-chasing aspirations or Instagram ambitions of foreigners.

The combination of big exporters, State sector and small businesses, one might say, is the critical component of NZ society. Not tourism, not foreign student education, not bars, restaurants, sports and other forms of mass entertainment. These can be resurrected when the pandemic has passed, but this moment of crisis demonstrates where value is created and preserved in NZ society. And it is not with hedge funds, sports teams, video game arcades, waterfront restaurants with space for tips on their service bills, ski resorts, golf courses or heli-tours.

Needless to say, this is a broad brush depiction of the economy of excess in which we live. There are bound to be fine details that prove the exception to the rule such as it has been depicted here. But the gist is clear: NZ has, as a result of the market-oriented experiment of the last 30 plus years created a entire range of parasitic/opportunist capitalism that contributes relatively little of value to the domestic economy or to the population at large. It is this sector that needs to be excised thanks to the arrival of CV-19.

Calls for self-isolation are getting more forceful as the government ramps up its pandemic threat advisories. This type of quarantine is a form of physical separation based on notions of collective solidarity (and not a form of social distancing, as pundits have called it). People retreat into their homes out a sense of collective responsibility and empathy for others, hoping to weather the worst of the pandemic in order to flatten the curve of its distribution. Here again, the burden of sacrifice is borne by small producers, public servants and waged labour, most of whom do not have access to the type of savings or surpluses that allow the corporates to ride out the storm.

It is these people that deserve government financial relief. Not the corporates or those in the bloated, non-essential and non-productive (in a value-added or material sense) sectors of the economy. Not those in parasitic financial sectors and non-traditional export industries. Not sports leagues and yachties.

In the end the CV-19 pandemic is not only a massive corrective to the world and NZ societies, demonstrating the dark and largely ignored side of the globalisation of production, consumption and exchange. It is more than an economic belt-tightening across the globe. It is a moment for pause and reflection on what living within one’s means really means in practice. For NZ, it means that the time has come to drop the growth is good mantra in certain non-critical sectors of the economy and to refocus energy and resources on those that comprise the economic triad underpinning the good society: “traditional” exporters, small businesses and the State-Owned and public/private enterprises that are the core of the national productive apparatus. This may require major adjustments in all three components, especially in the export sector (to include its very definition), but the moment has arrived thanks to the externality known as Coronavirus.

That result may be a smaller economy than what came before CV-19, but it will be more sustainable, efficient, value-generating and ultimately fairer for NZ society as a whole.