Pita Sharples has severely undermined his own and his party’s credibility with his Race Relations Day speech criticising “one person, one vote”. As a minister in a democratic government, he has taken aim at one of democracy’s fundamental symbolic virtues, in such a way as to give the impression he (and his party) are anti-democracy. After years of fighting for the voices of mana whenua to be heard in democratic politics on strong principled grounds, Sharples seems now to have accepted the extreme right’s framing of that representation as antithetical to democracy.

Pita Sharples has severely undermined his own and his party’s credibility with his Race Relations Day speech criticising “one person, one vote”. As a minister in a democratic government, he has taken aim at one of democracy’s fundamental symbolic virtues, in such a way as to give the impression he (and his party) are anti-democracy. After years of fighting for the voices of mana whenua to be heard in democratic politics on strong principled grounds, Sharples seems now to have accepted the extreme right’s framing of that representation as antithetical to democracy.

Let’s just be clear: “one person, one vote” is no sort of actual democracy, it is an illusory ideal which persists only in hearts and minds, placed there by bold principles and the stirring oratories brought by democratic leaders of old looking to appeal to something bigger than they were. Even our present democracy, which is a very great deal closer to the ideal than the original American system, is pretty far from “one person, one vote” at a functional level. For a start, we have two votes. Even if you had one, what sort of vote would it be: first-past-the-post, where you’re at the mercy of geography; or single-transferable, where you’re not sure until after it’s all over who your vote actually got counted for; or what? For another thing, you can be a person and not have a vote — people under 18 don’t, prisoners convicted of serious offences don’t (and that could soon include all prisoners). There are more, but I won’t go on — the point is that “one person, one vote” is symbolic, not literal.

But neither are Sharples’ objections literal, they are symbolic. In the non-literal sense, what “one person, one vote” means is the opportunity for equality of input into the electoral process — whether that be by one or two votes, in a big electorate or a small one. What happens after that is democracy in action. In this regard, an electoral system which pays at least some regard to the principle of “one person, one vote” is a minimal bound for a modern democracy (though there are others also). Sharples’ criticism is that this isn’t enough — that democracy should be about equality of outcome rather than input. I agree — and I think very many other people do as well. Making democracy work takes much more than votes. But when it’s framed in the way he has framed it, this sort of discussion is political poison, because it attacks the heart of our political culture. This “race-based” framing of mana whenua political representation has been expressly developed in order to make those things seem indefensible in a liberal democratic context. Sharples has swallowed the hook, and instead of continuing to defend the MÄori Seats and mana whenua representation on the existing and well-proven grounds (that it’s necessary for the establishment and maintenance of tino rangatiratanga, guaranteed by the Treaty) he has made a declaration which amounts to “yeah, they’re anti-democratic: so?” The most ridiculous aspect of it is that the existing mechanism which is so reviled complies with the principle of “one person, one vote”: electors on the MÄori roll get get the same vote as anyone else, the only difference is in how they cast it. There is equality of input to the democratic process by MÄori at the electoral level — it’s elsewhere in the process which is the problem.

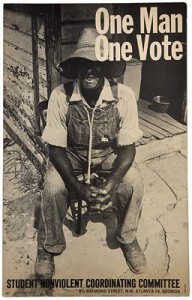

I’ve argued before that the core symbolic and philosophical stuff of modern democracy is liberalism of one brand or another. No mainstream political concern can hope to win a democratic mandate without founding a lot of its agenda in liberalism. The symbolism of “one person, one vote” is crucial to this orthodoxy. Charles Elder and Roger Cobb, in The Political Uses of Symbols presented a typology of political symbols in the American context, organised into “political community” symbols which express political values at the highest level (“America”, “The Flag”, “The Constitution”); through “regime” symbols which express the political values of the current orthodoxy (in this case, American democracy, not a specific administration — the examples given are “The Presidency”, “Congress”, and “One Person, One Vote”); and three classes of “situational” symbols which express particular policy or administrational preferences of lesser affect (“The Reagan Administration; “gun control”, etc.) The higher up Elder and Cobb’s typology you go, the greater the degree of political consensus on the values imbued in a particular symbol. Nobody in American politics gets anywhere if they stand against “America”: the task of politics in that context is to convince people that what you stand for is “America”. “One person, one vote” is pretty high up that symbolic ladder. It is an illusion, but it’s a sacred illusion.

Every party in New Zealand’s parliament at present, except one, lays claim to this broad liberal tradition in one way or another. That one party which does not is the mÄori party. That is not to say that their agenda isn’t broadly liberal in function, but that it’s largely that way for non-Western-liberal philosophic reasons. This is the mÄori party’s great electoral purpose: to normalise an indigenous political-philosophical tradition. But they can’t do so this way, by attacking the liberal orthodoxy’s sacred illusions, the bedrock values held even by those who would never dream of calling themselves liberals. The mÄori party, more than any other, must recognise the value of “one person, one vote” as part of the history of democracy working for downtrodden minorities rather than against them, and adopt this as part of its own political basis.

As libertarians have discovered, if you don’t really believe in democracy it’s best not to bother with it — then you get to maintain whatever you claim as high moral ground and leave the actual business of governing to those who lack your unshakeable principles. But that’s not what the mÄori party is about. They do believe in democracy; they do recognise the importance of engagement and compromise and consensus, and they do plenty of work toward it, and a misguided outburst like this one puts it all in jeopardy. “Race-based” is National’s catch-cry from just a few short years ago, and they will take any encouragement given them to reach out to New Zealand’s conservatives, who are already distrustful of the mÄori party. It will force Labour further down the path of attacking the mÄori party to try to recapture the centre ground, rather than encouraging cooperation and the mending of fences. Most critically, it could create a backlash against the very mechanism Sharples seeks to save, generating opposition to the MÄori seats his party needs for its survival, and which exist only by the pleasure of the PÄkehÄ majority whose sacred illusions he has slighted.

While it should have been underway already, the mÄori party must now redouble its efforts to appeal to voters outside the MÄori electorates, and prepare to live in a world without them.

L