This morning I posited a conspiracy theory that the government would use the temporary deregulation measures undertaken in response to the Canterbury earthquake to progress another tranche of wide-ranging reforms to the resource management regime and building and construction industries after the 2011 election.

Absurdly, if the Canterbury Earthquake Response and Recovery Bill is passed without very extensive amendments of the sort proposed by the Greens and voted down by both major parties (it’s going through all three stages right now), then all that and much, much more could happen this week, no election required, and without any review by the courts. The executive powers granted to the relevant Minister (that’s Gerry Brownlee) in this bill are so sweeping as to permit him to do almost literally anything as long as it has something to do with quake recovery — amend or suspend almost any piece of legislation, overturn any electoral decision — really, Dean Knight, Graeme Edgeler and Andrew Geddis (themselves no wide-eyed conspiracy nuts) are just three of the constitutional law experts who are boggling at the possibilities; Idiot/Savant is also much more than usually incandescent, and Gordon Campbell pulls few punches, either. Geddis says the law gives him “a case of the screaming collywobbles”. How’s that for a technical term. Their argument — contra government speakers such as Nick Smith — is that, because there is no real oversight to test whether actions taken are “reasonably necessary or expedient for the purpose of the Act”, the bill’s scope is not strictly limited in black-letter law to those matters, nor indeed to the region impacted by the quake, and the minister and his commission basically enjoy immunity. These are sweeping powers such as those which might be accorded an executive head of state in a command-government situation such as a major war.

Not would happen, mind. I don’t think anyone genuinely thinks Gerry Brownlee will decriminalise murder, approve mining across all schedule 4 land, enact wartime conscription or overrule the results of the forthcoming Supercity election. I don’t. But the point is (assuming Dean Knight knows what he’s talking about) that Brownlee can. Or will be able to tomorrow, until April 2012, which astute readers will note is a good half-year after the next general election must be held. There are no real checks or balances, much of the actions taken under this legislation are able to be taken in secret, and actions taken will not — at least on paper — be subject to judicial review. This means that we are relying on Gerry Brownlee to not be evil. But democracy doesn’t work on the honour system. It can’t. It doesn’t work on the basis that you give a government power in the hope that they use it legitimately; you give it power on the basis that you have the authority and ability to wrest it back from them if they misuse it, and on the assumption they will misuse it. The honour system is fine for bouquets being sold at the cemetery gates. It’s no basis upon which to run a country.

As I’ve often argued here and elsewhere, what sets liberal democracy, with all its failings, apart from authoritarian systems is the ability for the electorate to transfer power by the exercise of these sorts of checks and balances. Under orthodox authoritarian socialism for examplem — more or less the only form of socialism ever fully implemented on a nationwide scale, in the USSR and China, for instance — the transitional dictatorship is empowered with the sole authority and means to put down any such counter-revolution as might endanger the transition to genuine communism; and because of this, the dictatorship enjoys impunity. It has no reason to work in the interests of the people it purports to serve, inevitably becoming inefficient, corrupt and brutal. (Thus, the problem with socialism is authoritariansm which accompanies it, not so much the economic aspects, but that isn’t my point here).

The Canterbury Earthquake Response and Recovery Bill, of all the ridiculous things, brings into being the potential for just such a regime in New Zealand, and we can only hope it is not used to that effect. It is a colossal, hypervigilant overreach. And if any ill comes from this, Labour — and even the Greens and the mÄori party — will bear as much responsibility as National; they are all supporting it out of “unity”.

Where now are those who railed against the Electoral Finance Act, who speculated darkly that Helen Clark might not relinquish power after the election, or might suspend the operation of the free press; who shrieked about the Section 59 repeal; against ‘Nanny State’ and the illusory Stalinism of lightbulbs and shower heads, drink-drive limits and alcohol purchase ages and compulsory student union membership? Here the papers are being signed to dismantle robust constitutional democracy right under our very noses, and there’s barely a whimper.

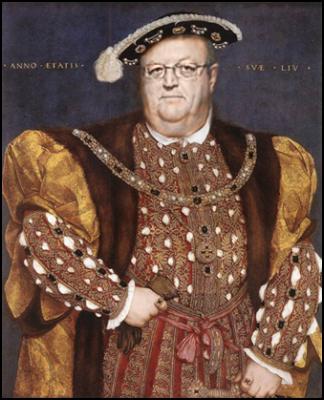

(Updated to add Lyndon Hood’s fantastic image of Brownlee VIII, link to Campbell’s article, and tidy the post up a bit.)

L