The last few decades have seen a world in increasing turmoil. Technological advances, climate deterioration, sharpening domestic and international political conflict and global pandemics are just some of the hallmarks of the contemporary world moment. In this essay I hope to outline some of the dynamics of this time by conceptually framing its recent historical underpinnings.

Think of international relations as a complex system. Because it involves living creatures (humans), rather than inanimate objects, we can think of it as an ecosystem made up of people and their institutions, norms, rules and the behaviours (confirmative or transgressive) that flow from them. The world order is comprised of various subsystems, including regional (meso) and national (micro) systems that encompass economic, political/diplomatic and socio-cultural features linked to but distinct from the global (macro) system.They key is to understand international relations and world politics as a malleable human enterprise.

International systems are dynamic, not static. Although they may enjoy long periods of relative stability or stasis, they are fluid in nature and therefore prone to change over time. In the last century stable world order cycles have become shorter and transitional cycles have become longer due to a number of factors, including technological advances in areas such as transportation and telecommunications, demographic shifts, the globalisation of production, consumption and exchange, ideological diffusion, cultural transfer and increased permeability of national borders. Status quos are more short-lived and transitional moments–moments leading to systemic realignment–are decades in length.

We are currently in the midst of such a long transitional moment.

In fact, the post-Cold War era is a period of long transition. After the fall of the USSR in 1990, the international order moved away from a tight bi-polar system where two nuclear-armed superpowers and their respective alliance systems deterred and balanced each other through credible counter-force based on second-strike capabilities in the event of strategic nuclear war. The bipolar alliance systems were “tight” in the dual sense that their diplomatic and military perspectives were closely bound to those of their respective superpowers (think NATO and the Warsaw Pact), and States in each security bloc tended to trade preferentially with each other (known as trade and security issue linkage).

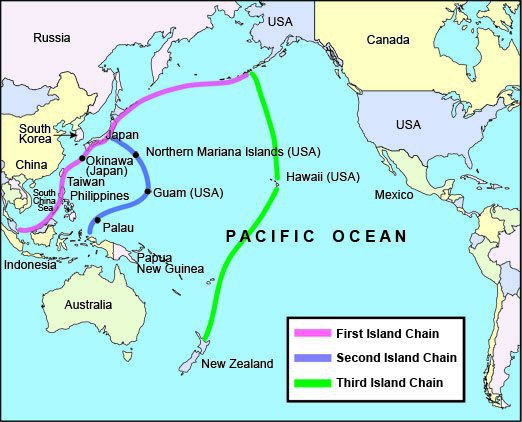

The geopolitical map of the Cold War was divided into shatter and peripheral zones, with the former being places where direct superpower confrontation was probable and therefore to be avoided (such as Central Europe and East Asia), and the latter being places where the probability of escalation was low and therefore conflicts could be “managed” at the sub-nuclear level because no existential threats to the superpowers were involved (SE Asia, Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa and the South Pacific come to mind). Here proxy wars, guerrilla conflicts and direct superpower interventions could flourish as trialing grounds for great power weaponry and ideological supremacy, but the nature of the conflicts were opportunistic or expedient, not existential for the superpowers and their major allies. Escalation was dangerous in shatter zones; escalation was limited in the periphery.

With the demise of the USSR the bipolar world was replaced by a unipolar world where the US was the sole superpower and therefore considered the “hegemon” (in international relations jargon) where its economic, military and political power was unmatched by any one country or group of countries. This is noteworthy because “hegemonic” superpowers intervene in the international system for systemic reasons. That is, they approach the international system in ways that preserve an institutional and regulatory status quo that supports and reaffirms their position of dominance. In contrast, great and middle powers intervene in the international system in order to pursue national interests rather than systemic values. Absent a hegemon to act as systems regulator, this may or may not lead to disorder.

The hegemonic premise is the conceptual foundation of the liberal international foreign policy approach adopted by US administration and many of its allies (including NZ) during the post -Cold War period and which persists to this day. For the West, the combination of market economics and liberal democracy is the preferred political-economic form because it is seen as the best way to achieve peace and prosperity for its subjects. As a result, it needs to be expanded globally and supported by a “rules-based” international institutional order crafted in its image. Although this belief was honoured most often in the breach (as any number of US-backed military coups d’état demonstrate), it constituted the ideological foundation for post-Cold War international relations because there was no global alternative to it.

US dominance as the sole superpower and global “hegemon” lasted little more than a decade. After the 9/11 attacks (which were not, in spite of their horrifying spectacle, an existential threat to the US unless it over-reacted), the US engaged in a series of military adventures under the umbrella justification of fighting the (sic) “war on terror.” In doing so it engaged in what may be called neo-imperial hubris, which in turn led to neo-imperial overreach. By invading Iraq and extending the (arguably legitimate) original irregular warfare mission against the Taliban and al-Qaeda in Afghanistan into an open-ended nation-building exercise, then invading Iraq on a pretext that it was involved in the 9/11 plot while conducting counter-terrorism operations in the Middle East, Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, Southeast Asia and even in the wider European Rim, the US expended vast amounts of blood and treasure in pursuit of the unachievable goal of redrawing the map of the Middle East in an US-centred image.

That is because although terrorists can be physically eliminated, the ideas that propel them cannot, and unless there is an ideological project that can counter the ideological beliefs of the “extremists,” then the physical wars are a short-term solution to a long-term problem. The US (and the West in general) lacked an ideological counter to Wahabism and Salafism, so the roots of Islamic extremism remain even if its human materiel has been depleted. In addition, pursuing a war of opportunity (rather than of necessity) in Iraq only generated concern and resentment in the Arab world and laid the foundations of the emergence of ISIS as an irregular Sunni fighting force, prompted Iran to pursue its nuclear deterrence option, and diverted resources from the fight in Afghanistan. That in turn allowed the latter to turn into a tar baby for the ISAF coalition fighting the Taliban and various Sunni irregular groups, which eventually produced the graveyard of Empire scenes at Kabul and Bagram airports in 2022.

More importantly for our purposes, despite its surface appearances and the claims of some scholars that a unipolar international hierarchy is the most stable systemic arrangement, a unipolar world is inherently an unstable world. As the hegemon attempts to maintain its dominance in the international order by engaging in wars of conquest, military interventions in peripheral areas or by attempting to be the world’s “policeman” in parallel with economic and diplomatic efforts across the globe, it expends its power on several dimensions. At the same time, pretenders to the throne build their power while avoiding direct confrontations with the superpower until the balance shifts in their favour and the time becomes ripe for a challenge. That is the time when the knives come out. That time could well have arrived and the moment of long transition may be coming to a head.

The move from a unipolar to a multipolar world still in the making began on 9/11 and continues to this day. There is good and bad news in this transition. The good news is that multipolar systems characterised by competition and cooperation among a small odd number (3-7) of great powers is arguably the most stable of international orders because it allows each State to form alliances on specific issues and balance or counter-balance the ambitions of others. The preferred configuration is an odd number because that avoids deadlocks and facilitates cross-cutting alliance formation on specific issues. This leads to a situation where balancing becomes a primary feature and objective of the international system as a whole. In a sense, it is the geopolitical equivalent of the invisible hand of the market: actors act in pursuit of their preferred interests and with a desire to secure preferred outcomes, but it is the aggregate of their actions that leads to balancing and realignment. Actors may wish to steer outcomes in their favour but what eventuates is seldom in line with their individual preferences. Instead, multipolar “market” clearance rests on a dynamic balance of great power national interests..

The bad news is that in the period of transition between unipolar and multipolar orders, consensus on the rules governing State behaviour and adherence to institutional edicts and mores breaks down. International norm erosion becomes widespread, uncertainty becomes generalised and conflict becomes the systems regulator. A lack of enforcement capability by international organisations and States themselves allows norm violations to proceed unchecked and perpetrators to act with impunity (as see, for example, in Syria, the South China Sea or the Ukraine). While geopolitical shatter and peripheral zones continue to exist (albeit not as they existed during the Cold War), the majority of the world becomes contested space in which State, multinational and non-state actors vie for influence using a mix of power variables (say, for instance, chequebook and debt diplomacy, direct influence operations or trade and security agreements). This includes cyber- and outer space, which are increasingly at the forefront of hostile great power contestation.

In a sense, the transitional moment marks a return to a Hobbesian “state of nature” where, absent a Leviathan (the hegemonic power), States and non-state international actors use their power to achieve self-interested goals rather than communitarian ideals.

Transitional conflicts may be economic, cultural, political, military or some combination thereof. In the present moment conflicts are increasingly hybrid in nature, with mixes of persuasive and dissuasive (using mixtures of soft, hard, smart and sharp) power operating on multiple dimensions that, due to technological advancements, do not respect national sovereignty. States and non-state actors now appeal to and influence the predilections of foreign audiences in direct ways that might be called “intermestic” or “glocalized:” what is foreign is also domestic, what is local is global. For hostile actors, the objective of hybrid warfare campaigns that use direct influence tactics is to undermine the enemy from within rather than attack it from without.

There is little governmental filter or defence against such penetrations (say, on social media) and the responses are usually reactive rather than proactive in any event. This is a major problem for liberal democracies that value freedoms of speech and association because often the aim of recent adversarial sharp power campaigns (commonly labeled as disinformation campaigns) is to corrode domestic support for democracy as a form of governance. Because of their repressive nature, authoritarian regimes do not have quite the same problem when confronted by foreign direct influence operations. In that sense, as China and Russia have understood, freedoms of speech, movement and association in liberal democracies constitute Achilles heels that can be exploited by hybrid power direct influence campaigns.

Norm erosion, increased uncertainty and the rise of hybrid conflict as the systems regulator have encouraged the emergence of more authoritarian (here defined as command-oriented rather than consultative in approaches to governance and policy-making), less Western-centric approaches to international relations. The liberal international consensus failed to deliver on its promises in most of the post-colonial world as well as in many advanced democracies, so alternatives began to appear that challenged its basic premise. Many of these have a regressive character to them, characterised by a shift to economic nationalism, anti-immigration policies, and a focus on restoring “traditional” values. After decades of promoting free trade, multilateralism and open borders, the last decade has seen a turn inwards that has encouraged nationalistic authoritarian solutions to domestic and international problems.

National populism is one manifestation of the rejection of the liberal democratic order, and the Asian Values school of thought converged with anti-colonial and anti-imperialist sentiment to reject liberal internationalism on the global plane. Instead, the emphasis is on efficiency under strong centralised leadership grounded in nationalist principles rather than on transparency, multilateralism, inclusion and representativeness. Throughout the world democracy (both as a form of governance as well as a social characteristic) is in decline and authoritarianism is on the rise, with their attendant influence on the conduct of foreign policy and international relations.

This brings up one more aspect of transitional moments leading to systemic realignment: competition between rising and declining powers.

The shift between international systems is at its core the result of competition between ascendent and descend great powers. Ascendency and decline can be the result of economic, military, social or ideological factors. States in decline will attempt to maintain their positions against the challenges of new or resurgent rivals. The competition between them can theoretically be managed peacefully if States accept their fate and trust each other to engage with mutual respect. In reality, transitional competition between rising and declining powers is often existential in nature (at least in the eye of those involved), and if multidimensional conflict turns to war it is usually the declining power that starts it. World War I can be seen in this light, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine is a contemporary case in point. Although the US is also in decline, it is undergoing a gradual rather than a rapid loss of power and status. Instead of being a new form of politics, Trump and MAGA are the product of a deep long-term malaise that is as socio-cultural as it is political. Trumpism may act as an accelerant in hastening the US decline but it is not, as of yet, immediately terminal.

Russia, on the other hand, is faced with a societal decline (low birthrates, ageing population, pervasive corruption, export commodity dependence, severely distorted income distribution and social anomaly) that is immediate and likely irreversible. It has an economy equivalent in size to that of Spain or the US state of Texas rather than those of Japan, Germany, China or the US. The invasion of Ukraine, phrased in revisionist “return-to-Empire” language, is a last ditch effort to gain both people and land in order to arrest the decline (because annexing Eastern and Southern Ukraine would provide a younger population of Russian speakers, fertile agricultural lands, a non-extractive manufacturing base and warm water trading ports for Russian goods and imports).

Given Ukraine’s and the NATO response, this is akin to the last gasp of a drowning person. No matter whether it “wins” or loses, Russia will be permanently diminished by having undertaken this war. As it turns out, rather than the US, Russia is the great power whose decline motivated the march to war and which will precipitate the emergence of a new multipolar world order.

What might this new multipolar international system look like? A decade ago there was agreement that Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) would emerge as great powers and vie with the US on the global stage. India and China clearly remain as emerging great powers. However, Brazil and South Africa have failed to achieve that status due to internal dysfunctions exacerbated by poor political leadership. Rather than restore some of its Empire, Russia is committing an act of national Hara kiri in Ukraine and has lost its chance at genuine great power status in the post-war future .

So who might emerge if not the BRICs? Germany and Japan clearly have the resources and means to join the new multipolar constellation. Beyond that, the picture is cloudy. The UK is in obvious long-term decline and France is unable to elevate beyond its regional power status. No Middle Eastern, Latin American, SE Asia, Central Asian or African country can do more than become a regional power. Nordic and Mediterranean Europe States can complement but not replace powers like Germany in a multipolar world. Australia and Indonesia may someday emerge as rightful contenders for great power status but that day is a ways off. The US will remain as great rather than a superpower, so perhaps the making of a new multipolar order will involve it, China, India and restored Axis powers finally emerging from the ashes of WW2.

On interesting prospect is that both during the transition to a new multipolar world and once it has consolidated, small and medium States may have increased flexibility nd room to manoeuvre between the great powers. This is due to balancing focus of the new constellation, which its a premium on forging alliances on specific issues. That can encourage smaller states to get more involved in negotiations between the great powers, thereby augmenting their diplomatic influence in ways not seen before. On the other hand, if the opportunity is not recognised by the great powers or seized by smaller States, then the broadening of the multipolar constellation to include satellite alliances around specific great power positions will have been lost.

Hybridity as a transitional hallmark extends beyond warfare and traditional conflict and into the world of so-called “grey area phenomena.” It now refers to the the merging of criminal and State organisations in pursuit of a common purpose that serves their mutual interests. Cyber-hacking is the clearest case in point, where state actors like the Russian GRU signals intelligence unit collude with criminal organisations in cyber theft or cyber disruption campaigns. This hand-in-glove arrangement allows them to share technologies in pursuit of particular rewards: money for the criminals and intellectual property theft, security breaches or backdoor vulnerabilities in foreign networks for the state actor. China. Israel, North Korea and Iran are considered prime suspects of ending in such hybrid activities.

Externalities have been magnified during the long transitional moment. In particular, the Covid pandemic has revealed the crisis of contemporary capitalism and the relative levels of government incompetence around the world. The need to secure national borders and curtail the movement of people and goods across entire regions demonstrated that features like commodity concentration, “just-in-time” production, debt-leveraged financing and other late capitalist features exacerbated the costs of and impeded effective response to the pandemic. In turn, the pandemic exposed government corruption and incompetence on a global scale, where the Peter Principle (a person or agency rises to its own level of incompetence) separated efficient from failed pandemic mitigation policy. Where partisan politics interfered with the application of scientific health policy, the situation was made worse. The US, UK, Russia and Brazil are examples of the latter; NZ, Uruguay, Singapore and Taiwan are generally considered to be examples of the former.

What all of this means is that in the post-pandemic future multipolarity will emerge as the new global alignment under conditions of great uncertainty that produce different rules, prompt institutional reform and which promote different international behaviours. Capitalism will have to adapt and change (such as through near-shoring and friend-shoring investment strategies and a decentralisation of commodity production, perhaps including a return to national self-sufficiency in some productive areas and an embrace of competitive rather than comparative advantage economic strategies). “Living within our means” based on sustainability will become an increasingly common policy approach for those who understand the gravity of the moment.

The most change, however, is in the field of post-pandemic governance. The frailties of liberal democracy have been glaringly exposed, including corruption, lack of transparency, sclerotic systems of representation and voice, and pervasive nepotism and patronage in the linkage between constituents and elected officials. Authoritarians have emerged as alternatives in both historically democratic as well as traditionally undemocratic political systems, with that trend set to continue for the near future. That may or not be a salve rather than a solution to the deep seated problems afflicting global society but what it does demonstrate is that not only is the multipolar future uncertain to discern, but the systemic realignment may not necessarily lead to a more peaceful, egalitarian and representative constellation than what we have seen before.

Only time will tell what our future holds.

*This essay is written as a think piece that will serve as the basis for a public lecture the author will deliver to the World Affairs Forum in Auckland on October 10, 2022.