Coming on the heels of the recently signed Solomon Islands-PRC bilateral economic and security agreement, the whirlwind tour of the Southwestern Pacific undertaken by PRC Foreign Minister Wang Yi has generated much concern in Canberra, Washington DC and Wellington as well as in other Western capitals. Wang and the PRC delegation came to the Southwestern Pacific bearing gifts in the form of offers of developmental assistance and aid, capacity building (including cyber infrastructure), trade opportunities, economic resource management, scholarships and security assistance, something that, as in the case of the Solomons-PRC bilateral agreement, caught the “traditional” Western patrons by surprise. With multiple stops in Kiribati, Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, PNG, Vanuatu and East Timor and video conferencing with other island states, Wang’s visit represents a bold outreach to the Pacific Island Forum community.

A couple of days ago I did a TV interview about the trip and its implications. Although I posted a link to the interview, I thought that I would flesh out was what unsaid in the interview both in terms of broader context as well as some of the specific issues canvassed during the junket. First, in order to understand the backdrop to recent developments, we must address some key concepts. Be forewarned: this is long.

China on the Rise and Transitional Conflict.

For the last three decades the PRC has been a nation on the ascent. Great in size, it is now a Great Power with global ambitions. It has the second largest economy in the world and the largest active duty military, including the largest navy in terms of ships afloat. It has a sophisticated space program and is a high tech world leader. It is the epicenter of consumer non-durable production and one of the largest consumers of raw materials and primary goods in the world. Its GDP growth during that time period has been phenomenal and even after the Covid-induced contraction, it has averaged well over 7 percent yearly growth in the decade since 2011.

The list of measures of its rise are many so will not be elaborated upon here. The hard fact is that the PRC is a Great Power and as such is behaving on the world stage in self-conscious recognition of that fact. In parallel, the US is a former superpower that has now descended to Great Power status. It is divided domestically and diminished when it comes to its influence abroad. Some analysts inside and outside both countries believe that the PRC will eventually supplant the US as the world’s superpower or hegemon. Whether that proves true or not, the period of transition between one international status quo (unipolar, bipolar or multipolar) is characterised by competition and often conflict between ascendent and descendent Great Powers as the contours of the new world order are thrashed out. In fact, conflict is the systems regulator during times of transition. Conflict may be diplomatic, economic or military, including war. As noted in previous posts, wars during moments of international transition are often started by descendent powers clinging or attempting a return to the former status quo. Most recently, Russia fits the pattern of a Great Power in decline starting a war to regain its former glory and, most importantly, stave off its eclipse. We shall see how that turns out.

Spheres of Influence.

More immediate to our concerns, the contest between ascendent and descendent Great Powers is seen in the evolution of their spheres of influence. Spheres of influence are territorially demarcated areas in which a State has dominant political, economic, diplomatic and military sway. That does not mean that the areas in question are as subservient as colonies (although they may include former colonies) or that this influence is not contested by local or external actors. It simply means at any given moment some States—most often Great Powers—have distinct and recognized geopolitical spheres of influence in which they have primacy of interest and operate as the dominant regional actor.

In many instances spheres of influence are the object of conquest by an ascendent power over a descendent power. Historic US dominance of the Western Hemisphere (and the Philippines) came at the direct expense of a Spanish Empire in decline. The rise of the British Empire came at the expense of the French and Portuguese Empires, and was seen in its appropriation of spheres of influence that used to be those of its diminished competitors. The British and Dutch spheres of influence in East Asia and Southeast Asia were supplanted by the Japanese by force, who in turn was forced in defeat to relinquish regional dominance to the US. Now the PRC has made its entrance into the West Pacific region as a direct peer competitor to the US.

Peripheral, Shatter and Contested Zones.

Not all spheres of influence have equal value, depending on the perspective of individual States. In geopolitical terms the world is divided into peripheral zones, shatter zones and zones of contestation. Peripheral zones are areas of the world where Great Power interests are either not in play or are not contested. Examples would be the South Pacific for most of its modern history, North Africa before the discovery of oil, the Andean region before mineral and nitrate extraction became feasible or Sub-Saharan Africa until recently. In the modern era spheres of influence involving peripheral zones tend to involve colonial legacies without signifiant economic value.

Shatter zones are those areas where Great Power interests meet head to head, and where spheres of influence clash. They involve territory that has high economic, cultural or military value. Central Europe is the classic shatter zone because it has always been an arena for Great Power conflict. The Middle East has emerged as a potential shatter zone, as has East Asia. The basic idea is that these areas are zones in which the threat of direct Great Power conflict (rather than via proxies or surrogates) is real and imminent, if not ongoing. Given the threat of escalation into nuclear war, conflict in shatter zones has the potential to become global in nature. That is a main reason why the Ruso-Ukrainian War has many military strategists worried, because the war is not just about Russia and Ukraine or NATO versus Russian spheres of influence.

In between peripheral and shatter zones lie zones of contestation. Contested zones are areas in which States vie for supremacy in terms of wielding influence, but short of direct conflict. They are often former peripheral zones that, because of the discovery of material riches or technological advancements that enhance their geopolitical value, become objects of dispute between previously disinterested parties. Contested zones can eventually become part of a Great Power’s sphere of influence but they can also become shatter zones when Great Power interests are multiple and mutually disputed to the point of war.

Strategic Balancing.

The interplay of States in and between their spheres of influence or as subjects of Great Power influence-mongering is at the core of what is known as strategic balancing. Strategic balancing is not just about relative military power and its distribution, but involves the full measure of a State’s capabilities, including hard, soft, smart and sharp powers, as it is brought to bear on its international relations.

That is the crux of what is playing out in the South Pacific today. The South Pacific is a former peripheral zone that has long been within Western spheres of influence, be they French, Dutch, British and German in the past and French, US and (as allies and junior partners) Australia and New Zealand today. Japan tried to wrest the West Pacific from Western grasp and ultimately failed. Now the PRC is making its move to do the same, replacing the Western-oriented sphere of influence status quo with a PRC-centric alternative.

The reason for the move is that the Western Pacific, and particularly the Southwestern Pacific has become a contested zone given technological advances and increased geopolitical competition for primary good resource extraction in previously unexploited territories. With small populations dispersed throughout an area ten times the size of the continental US covering major sea lines of communication, trade and exchange and with valuable fisheries and deep water mineral extraction possibilities increasingly accessible, the territory covered by the Pacific Island Forum countries has become a valuable prize for the PRC in its pursuit of regional supremacy. But in order to achieve this objective it must first displace the West as the major extra-regional patron of the Pacific Island community. That is a matter of strategic balancing as a prelude to achieving strategic supremacy.

Three Island Chains and Two Level Games.

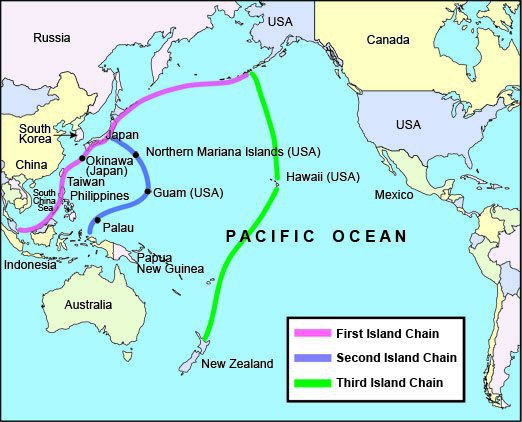

The core of the PRC strategy rests in a geopolitical conceptualization known as the “three island chains” This is a power projection perspective based on the PRC eventually gaining control of three imaginary chains of islands off of its East Coast. The first island chain, often referred to those included in the PRC’s “Nine Dash Line” mapping of the region, is bounded by Japan, Northwestern Philippines, Northern Borneo, Malaysia and Vietnam and includes all the waters within it. These are considered to be the PRC’s “inner sea” and its last line of maritime defense. This is a territory that the PRC is now claiming with its island-building projects in the South China Sea and increasingly assertive maritime presence in the East China Sea and the straits connecting them south of Taiwan.

The second island chain extends from Japan to west of Guam and north of New Guinea and Sulawesi in Indonesia, including all of the Philippines, Malaysian and Indonesian Borneo and the island of Palau. The third island chain, more aspirational than achievable at the moment, extends from the Aleutian Islands through Hawaii to New Zealand. It includes all of the Southwestern Pacific island states. It is this territory that is being geopolitically prepared by the PRC as a future sphere of influence, and which turns it into a contested zone.

(Source: Yoel Sano, Fitch Solutions)

The PRC approach to the Southwestern Pacific can be seen as a Two Level game. On one level the PRC is attempting to negotiate bilateral economic and security agreements with individual island States that include developmental aid and support, scholarship and cultural exchange programs, resource management and security assistance, including cyber security, police training and emergency security reinforcement in the event of unrest as well as “rest and re-supply” and ”show the flag” port visits by PLAN vessels. The Solomon Island has signed such a deal, and Foreign Minister Wang has made similar proposals to the Samoan and Tongan governments (the PRC already has this type of agreement in place with Fiji). The PRC has signed a number of specific agreements with Kiribati that lay the groundwork for a more comprehensive pact of this type in the future. With visits to Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and East Timor still to come, the approach has been replicated at every stop on Minister Wang’s itinerary. Each proposal is tailored to individual island State needs and idiosyncrasies, but the general blueprint is oriented towards tying development, trade and security into one comprehensive package.

None of this comes as a surprise. For over two decades the PRC has been using its soft power to cultivate friends and influence policy in Pacific Island states. Whether it is called checkbook or debt diplomacy (depending on whether developmental aid and assistance is gifted or purchased), the PRC has had considerable success in swaying island elite views on issues of foreign policy and international affairs. This has helped prepare the political and diplomatic terrain in Pacific Island capitals for the overtures that have been made most recently. That is the thrust of level one of this strategic game.

That opens the second level play. With a number of bilateral economic and security agreements serving as pillars or pilings, the PRC intends to propose a multinational regional agreement modeled on them. The first attempt at this failed a few days ago, when Pacific Island Forum leaders rejected it. They objected to a lack of detailed attention to specific concerns like climate change mitigation but did not exclude the possibility of a region-wide compact sometime in the future. That is exactly what the PRC wanted, because now that it has the feedback to its initial, purposefully vague offer, it can re-draft a regional pact tailored to the specific shared concerns that animate Pacific Island Forum discussions. Even if its rebuffed on second, third or fourth attempts, the PRC is clearly employing a “rinse, revise and repeat” approach to the second level aspect of the strategic game.

An analogy the captures the PRC approach is that of an off-shore oil rig. The bilateral agreements serve as the pilings or legs of the rig, and once a critical mass of these have been constructed, then an overarching regional platform can be erected on top of them, cementing the component parts into a comprehensive whole. In other words, a sphere of influence.

Western Reaction: Knee-Jerk or Nuanced?

The reaction amongst the traditional patrons has been expectedly negative. Washington and Canberra sent off high level emissaries to Honiara once the Solomon Islands-PRC deal was leaked before signature, in a futile attempt to derail it. The newly elected Australian Labor government has sent its foreign minister, sworn into office under urgency, twice to the Pacific in two weeks (Fiji, Tonga and Samoa) in the wake of Minister Wang’s visits. The US is considering a State visit for Fijian Prime Minister (and former dictator) Frank Baimimarama. The New Zealand government has warned that a PRC military presence in the region could be seriously destabilising and signed on to a joint US-NZ statement at the end of Prime Minister Ardern’s trade and diplomatic junket to the US re-emphasising (and deepening) the two countries’ security ties in the Pacific pursuant to the Wellington and Washington Agreements of a decade ago.

The problem with these approaches is two-fold, one general and one specific. If countries like New Zealand and its partners proclaim their respect for national sovereignty and independence, then why are they so perturbed when a country like the Solomon Islands signs agreements with non-traditional patrons like the PRC? Besides the US history of intervening in other countries militarily and otherwise, and some darker history along those lines involving Australian and New Zealand actions in the South Pacific, when does championing of sovereignty and independence in foreign affairs become more than lip service? Since the PRC has no history of imperialist adventurism in the South Pacific and worked hard to cultivate friends in the region with exceptional displays of material largesse, is it not a bit neo-colonial paternalistic of Australia, NZ and the US to warn Pacific Island states against engagement with it? Can Pacific Island states not find out themselves what is in store for them should they decide to play the Two Level Game?

More specifically, NZ, Australia and the US have different security perspectives regarding the South Pacific. The US has a traditional security focus that emphasises great power competition over spheres of influence, including the Western Pacific Rim. It has openly said that the PRC is a threat to the liberal, rules-based international order (again, the irony abounds) and a growing military threat to the region (or at least US military supremacy in it). As a US mini-me or Deputy Sheriff in the Southern Hemisphere, Australia shares the US’s traditional security perspective and emphasis when it comes to threat assessments, so its strategic outlook dove-tails nicely with its larger 5 Eyes partner.

New Zealand, however, has a non-traditional security perspective on the Pacific that emphasises the threats posed by climate change, environmental degradation, resource depletion, poor governance, criminal enterprise, poverty and involuntary migration. As a small island state, NZ sees itself in a solidarity position with and as a champion of its Pacific Island neighbours when it comes to representing their views in international fora. Yet it is now being pulled by its Anglophone partners into a more traditional security perspective when it comes to the PRC in the Pacific, something that in turn will likely impact on its relations with the Pacific Island community, to say nothing of its delicate relationship with the PRC.

In any event, the Southwestern Pacific is a microcosmic reflection of an international system in transition. The issue is whether the inevitable conflicts that arise as rising and falling Great Powers jockey for position and regional spheres of influence will be resolved via coercive or peaceful means, and how one or the other means of resolution will impact on their allies, partners and strategic objects of attention such as the Pacific Island community.

In the words of the late Donald Rumsfeld, those are the unknown unknowns.