In the coming years, core tenets of socialist and indigenist faith will be tested. Labour, with its recently-adopted ‘blue collars, red necks’ strategy, has struck out along a path which requires a large slice of its core constituency — MÄori — to search their political souls and choose between the renewed Marxist orthodoxy which privileges class above all else; and the progressive social movements developed over the past three or four decades which have produced a society tolerant enough to permit their unprecedented cultural renaissance.

The strategy indicated by Phil Goff’s speech appears to be substantially based on the simple calculus, most forthrightly argued by Chris Trotter, that ‘social liberals’ are fewer in number than ‘social conservatives’ among the proletariat, and therefore an appeal to ‘social conservatism’ will deliver more votes than the equivalent appeal to ‘social liberalism’. This is couched as a return to the old values of the democratic socialist movement — class struggle, and anything else is a distraction. But because the new political strategy is founded upon an attack on MÄori, it requires that working class solidarity wins out over indigenous solidarity and the desire for tino rangatiratanga in a head-to-head battle. MÄori must choose to identify as proletarians first and tangata whenua second. Similarly, the mÄori party’s alignment with National and subsequent intransigence on issues such as the Emissions Trading Scheme asks MÄori to privilege their indigeneity over material concerns.

An article of faith of both socialist and indigenist movements is that their referent of political identity trumps others: that all proletarians are proletarians first, and that all indigenous people are indigenous people above all else. In the coming years, unless Labour loses its bottle and recants, we will see a rare comparison as to which is genuinely the stronger. Much of the debate which has raged over this issue, and I concede some of my own contributions in this, has been people stating what they hope will occur as if it surely will. For this reason the test itself is a valuable thing, because it provides an actual observable data point upon which the argument can turn.

A spontaneous interlude: I write this on the train into Wellington, in a carriage full of squirming, shouting, eight and nine year-olds on a school trip to the city. In a (rare) moment of relative calm, a few bars of song carried from the next carriage, and the tune was taken up enthusiastically by the — mostly PÄkehÄ — kids in my carriage.

TÅ«tira mai ngÄ iwi (aue!)

TÄtou, tÄtou e.

(In English:

Line up together, people

All of us, all of us.)

Read into this what you wish; one of life’s little rorschach tests.**

Clearly, I don’t believe MÄori will abandon the hard-won fruits of their renaissance for a socialist pragma which lumps them and their needs in with everyone else of a certain social class, which in the long term would erase the distinction between tangata whenua and tangata Tiriti. This distinction will fade with time, but that time is not yet come. For this reason I believe the strategy is folly at a practical level. Add to which, the appeal to more conservative social values was always going to be strong among MÄori and Pasifika voters, so the left and right hands (as it were) of the socialist conservative resurgence seem unaware of what the other is doing: with the left hand, it beckons them closer, and with the right it pushes them away.

My main objection to the ‘blue collars, red necks’ strategy is not practical — although that would be a sufficient cause for opposing it. The main reason is because of principle, and this question turns on an assessment of the left in politics. Trotter and other old-school socialists (and presumably Pagani and Goff and the current leadership of the Labour party) believe that the left has been hijacked over the past generation by non-materialist concerns and has lost its way as a consequence. I believe that the wider social concern with non-material matters has saved socialism from its own dogma.

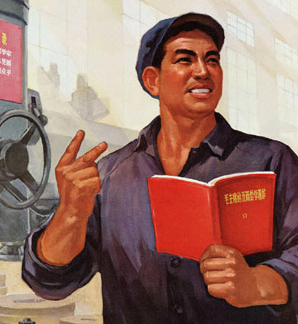

Largely discredited as an economic system and its legacy irretrievably tarnished by the catastrophic failure of practically every implementation, socialist-aligned parties on the left have been forced to diversify from a strict focus on what’s in the pockets of the proletariat to what’s in their heads — what they care about and who they are, their identity beyond being ‘the proletariat’. In doing so these movements have embraced liberalism, social equality movements, and environmentalism, and the resulting blend, termed ‘progressivism’ has become part of the political orthodoxy, such that the political right must now pay at least some mind to these considerations if it is to remain viable. This broadening, and the progressive movement’s redefinition of what is right by its general and gradual rejection of racism, sexism, sexual and religious discrimination, among others, has been hugely beneficial to society. For reasons of principle, it should not be discarded out of cynical political expedience.

Furthermore, maintenance of the social liberal programme has strategic, pragmatic value. It has enabled left political movements to broaden their support base and engage with groups often marginalised from politics, breaking the previously zero-sum rules. The modern Labour party has built its political church upon this rock of progressive inclusion, broadening its support base by forming strategic alliances with RÄtana from the time of the First Labour Government and less formally with the KÄ«ngitanga and other MÄori groups, to which the party owes a great deal of its political success. The progressive programme has broadened to include other groups historically marginalised by the conservative establishment. For Labour to shun its progressive history and return to some idealised socialist pragma of old by burning a century of goodwill in order to make cheap electoral gains by emulating their political opponents is the same transgression many on the economic left have repeatedly levelled against the mÄori party, and with some justification: selling out one’s principles for the sake of political expedience is a betrayal, and betrayals do not go unpunished. In this case, the betrayal is against the young, who will rapidly overtake the old socialist guard as the party’s future; and MÄori, who will rapidly overtake the old PÄkehÄ majority in this country’s future. The socialists might applaud, but Labour represents more than just the socialists, and it must continue to do so if it is to remain relevant.

So, for my analysis, the ‘blue collars, red necks’ strategy fails at the tactical level, because it asks MÄori to choose their economic identity over their cultural identity; it fails at the level of principle, because it represents a resort to regressive politics, a movement away from what is ‘right’ to what is expedient; and it fails at the level of strategy, because by turning its back on progressivism the party publicly abandons its constituents, and particularly those who represent the future of NZ’s politics, who have grown up with the Labour party as a progressive movement. It is triply flawed, and the only silver lining from the whole sorry affair is that (again, if Goff and Pagani hold their nerve) we will see the dogmatic adherence to class tested and, hopefully once and for all, bested.

L

* Of course, Goff claims it is no such thing. But Trotter sees that it is and is thrilled, and John Pagani’s endorsement of Trotter’s analysis reveals rather more about the strategic direction than a politician’s public assurance.

** I see this as an expression of how normalised MÄori-ness is among young people, and as much as can be said from the actions of nine-year-olds, an indicator of NZ’s political future.