The recent debates engaged here and elsewhere on the “proper” course to be taken by NZ Left/progressive politics has given me pause to think about the larger issue of Left/progressive praxis in a country such as this. I am on record as defending the class line-first approach, whereas Lew has quite eloquently expressed the primacy of identity politics (and, it should be noted, I am not as hostile to Lew’s line of thought as some of his other critics). But I do not think that the debate covered the entirety of the subject of Left/progressive praxis, and in fact may have detracted from it. Â Thus what follows is a sketch of my view of how Left/progressive praxis needs to be pursued in Aotearoa.

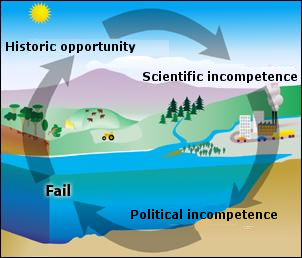

First, let’s set the stage. NZ is dominated by market-driven ideologies. In its social, cultural, political and economic expression, capitalism is the primary and undisputed organising principle. Counter-ideological resistance can be found in all of these domains, but the supremacy of capitalism as a social construct is clear. Even so, when compared with the 1990s, this supremacy is not as unshakable. The global financial crisis, corporate greed, predatory lending, financial market manipulation and fraud, increasing income disparities, assorted mendacious acts of venality and corruption have all contributed to a decline in the ideological legitimacy of market-driven logics, including those espoused by its political representatives. That provides a window of opportunity for Left/progressives, even if their traditional sources of strength in the union movement are no longer capable of exercising decisive leadership of a counter-hegemonic sort. Hence the need for a different type of praxis.

The Left/progressive cause needs to be organized into two branches: a political branch and a social movement branch. In turn, each branch needs to be divided into militant and moderate wings. The political branch would encompass Left/progressive political parties such as the Greens and the Alliance as well as fringe parties willing to cooperate in a common venture such as the Communists, Socialist Workers and the like. Because Labour is no longer a genuine Left Party, its inclusion is problematic, but it is possible that its leftist cadres could be invited to participate. The idea is to form a genuine Left/progressive political coalition that serves as a political pressure group on the mainstream parties while offering real counter-hegemonic alternatives to voters in selected districts. One can envision a Left coalition banner running slates in targeted districts with strong subaltern/subordinate group demographics. The idea is to present a Left/progressive alternative to the status quo that, at a minimum, pressures Labour out of its complacency and conformity with the pro-market status quo. At a maximum it will siphon disaffected voters away from Labour and into a genuine Left/progressive political alternative. This may be hard to do, but it is not impossible if properly conceived and executed.

In parallel, the social movement branch should encompass the now somewhat disparate assortment of environmental, union, animal welfare, indigenous rights, GBLT rights and other advocacy groups under the banner of common cause and reciprocal solidarity. The unifying pledge would be that of mutual support and advocacy. It goes without saying that the political and social movement branches will have areas of overlap in the guise of individuals with feet in each camp, but their strategic goals will be different, as will be their tactics. But each would support the other: the social movement branch would endorse and actively Left/progressive candidates and policy platforms; the Left/progressive political branch would support the social movement causes. This mutual commitment would be the basis for formal ties between and within each branch.Â

That brings up the moderate-militant wings. Each branch needs to have  both moderate and militant cadres if they are to be effective in pursuing a common agenda. The moderate wings are those that appear “reasonable” to bourgeois society, and who engage their politics within the institutional confines of the bourgeois state. The militant wings, on the other hand, are committed to direct action that transgresses established institutional boundaries and mores. Since this involves transgressing against criminal as civil law (even if non-violent civil disobedience such as the Plowshares action against the Echelon listening post in Blenheim), the use of small group/cell tactics rooted in autonomous decentralized acts and operational secrecy are paramount for survival and success.  The need for militancy is simple: it is a hedge against co-optation. Political and social militants keep their moderate brethren honest, which in turn allows the moderate wings to exploit the political space opened by militant direct action to pursue an incremental gains agenda in both spheres.

For this type of praxis to work, the key issues are those of organization and contingent compromise. Endongeonously, all interested parties in each branch will have to be capable of organizational unity, which means that principle/agent issues need to resolved in pursuit of coherent collective action, presumably in ways that forestall the emergence of the iron law of oligarchy that permits vanguardist tendencies to predominate. There are enough grassroots leaders and dedicated organisers already operating in the NZ milieu. The question is whether they can put aside their personal positions and parochial concerns in the interest of broader gains. That means that exogenously, these actors will need to find common ground for a unified platform that allows for reciprocal solidarity without the all-to-common ideological and tactical hair-splitting that is the bane of Left/progressive politics. The compromise between the political and social movement branches is contingent on their mutual support, but is designed to prevent co-optation of one by the other (such as what has traditionally tended to occur). If that can be achieved, then strategic unity between the political and social movement branches is possible, with strategic unity and tactical autonomy being the operational mantra for both moderate and militant wings.

On the face of things, all of this may sound quite simplistic and naive. After all it is only a sketch, and far be it for me, a non-citizen pontificating from my perch in authoritarian Asia, to tell Kiwi Left/progressives how to conduct their affairs. It may, in fact, be impossible to achieve given the disparate interests and personalities that would come into play, to say nothing of the resistance to such a project by the political status quo, Labour in particular. But the failures of Left/progressive praxis in NZ can be attributed just as much to its ideological and organizational disunity as it can be to the ideological supremacy and better organization of the Right. Moreover, Labour is in a position where it can no longer ignore groups that it has traditionally taken for granted, to include more militant union cadres who are fed up with being treated as corporate lapdogs and political eunuchs. Thus the time is ripe for a re-evaluation of Left/progressive strategy and action, particularly since the NACTIONAL agenda is now being fully exposed in all of its profit-driven, privatization-obsessed glory. Perhaps then, it is a time for a series of Left/Progressive summits in which all interested parties can attempt to forge a common strategy of action. It may take time to hash out such a platform, but the political rewards of such an effort could be significant. After all, la union hace la fuerza: with unity comes strength.