The “A View from Afar” podcast with Selwyn Manning and I resumed after a months hiatus. We discussed the PRC-Taiwan tensions in the wake of Nancy Pelosi’s visit and what pathways, good and bad, may emerge from the escalation of hostilities between the mainland and island. You can find it here.

Considering Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan.

I have said this in other forums, but here is the deal:

PRC military exercises after Pelosi’s visit are akin to silverback male gorillas who run around thrashing branches and beating their chests when annoyed, disturbed or seeking to show dominance. They are certainly dangerous and not to be ignored, but their aggression is about signaling/posturing, not imminent attack. In other words, the behaviour is a demonstration of physical capabilities and general disposition rather than real immediate intent. If and when the PRC assault on Taiwan comes, it will not be telegraphed.

As for why Pelosi, third in the US chain of command, decided to go in spite of PRC threats and bluster. Along with a number of other factors, it was a show of bipartisan, legislative-executive branch resolve in support of Taiwan to allies and the PRC in a midterm election year. SecDef Austin was at her side, so Biden’s earlier claims that the military “did not think that her trip was a good idea” did not result in an institutional rupture over the issue. The show of unity was designed to allay allied concerns and adversary hopes that the US political elite is too divided to act decisively in a foreign crisis while removing a basis for conservative security hawk accusations in an election year that the Biden administration and Democrats are soft on China.

The PRC can threaten/exercise/engage indirect means of retaliation but cannot seriously escalate at this point. It’s launching of intermediate range ballistic missiles over Taiwan and into Japan’s EEZ as part of the response to Pelosi’s visit certainly deserves concerned attention by security elites, as it signals a readiness by the PRC to broaden the conflict into a regional war involving more than the US and Taiwan. But the PRC is too economically invested in Taiwan (especially in microchips and semi-conductors) to risk economic slow downs caused by disruptions of Taiwanese production in the event of war (which likely will be a protracted affair as Taiwan reverts to the “hedgehog” defence strategy common among island nations and facilitated by Formosa’s terrain), and it is not a full peer competitor with the US when it comes to the East Asian regional military balance, especially if US security allies join the conflict on Taiwan’s side.

The PRC must therefore bide its time and wait until its sea-air-land forces are capable of not only invading and occupying Taiwan, but be able to do so in the face of US-led military response across all kinetic and hybrid warfare domains. Pelosi’s visit was a not to subtle reminder of that fact.

So the visit, while provocative and an act of brinkmanship given the CCP is about to hold its 20th National Party Congress in which President Xi Jinping is expected to be re-elected unopposed to another term in office, was at its most basic level simply conveying a message that the US will not be bullied by the PRC on what was a symbolic visit to a disputed territory ruled by an independent democratic government.

For the moment the PRC must content itself with mock charges and thrashing the bush in the form of large-scale military exercises and some non-escalatory retaliation against the US and Taiwan, but it is unlikely to go beyond that at the moment. It remains to be seen if this sits well with nationalists and security hardliners in the CCP who may see what they perceive to be the relatively soft response as a loss of face and evidence of Xi’s lack of will to strike a blow for the Motherland when he has the chance and which could have also served as a good patriotic diversion from domestic woes caused by Covid and the ripple effect economic slowdown associated with it.

In that light, the Party Congress should give us a better idea if the factional undercurrents operating within the CCP will now spill out into the open over the Pelosi’s visit. If so, perhaps there was even more to the calculus behind her trip than what I have outlined above.

Countering coercive politics

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s two week foreign mission to Europe and Australia was by all accounts a success. She met with business and government leaders, signed and co-signed several commercial and diplomatic agreements including a EU-NZ trade pact, conferred with NATO officials as an invited participant of this year’s NATO’s Leader’s Summit, gave several keynote speeches on foreign policy and international affairs, and in general flew the Aotearoa flag with grace and a considerable dose of celebrity. As she wraps up her visit to Australia, it is worth noting that she gave different takes on foreign policy to different audiences. These may appear incongruous at first glance but in fact display a fair degree of strategic and diplomatic finesse.

In Europe she emphasized the commonality of shared values among liberal democracies across a range of subjects: approaches to trade, security, human rights, representative governance, the rule of law within and across borders, transparency and rejection of corruption, and the common threat posed to all of these values by authoritarian great powers that are trying to usurp the international order via persistent challenges and encroachments on international norms and institutions.

Towards the end of her trip while in Australia, she shifted tack and emphasized NZ’s “independent” foreign policy while dropping the value-based view of a global geostrategic contest marshalled along ideological lines.

Instead, she publicly decoupled the Ruso-Ukrainian war from broader geostrategic competition between democratic and authoritarian-led powers, treating Russian behavior as idiosyncratic rather than as a result of regime type. That framing of the conflict avoids messy arguments about domestic political legitimacy and its impact on great power rivalries. In doing so Ardern reaffirmed the independence of NZ’s foreign policy approach from those of larger Western allies while reducing the possibility of retaliation by the PRC on trade and other diplomatic fronts. The PRC is well aware of the reality of NZ’s recent strategic shift towards the West, but a public position that pointedly refuses to lump together PRC behavior with Russian aggression based on the authoritarian nature of their respective regimes gives NZ some time and diplomatic space in which to maneuver as it charts a course in the international transitional moment that it is currently navigating. That is a prudent position to take and hence a good diplomatic move assuming that the PRC reads the statement as NZ intends it to be read.

The strategy behind this approach–one that recognizes the larger ideological divide at play in international affairs but treats State actions as unique to individual national history and circumstances–might be called a “confronting coercive politics” approach. Allow me to explain.

Politics ultimately is about the acquisition, accumulation, administration, distribution, maintenance and loss of power. Power is the ability to make others bend to one’s will. It can be persuasive or coercive in nature, i.e., it can induce others to act in certain ways or it can compell them to act under (threat of) duress .

Power is relative and variable across several dimensions, including economic, political, military, personal, class, social (including gender and reputational/”influencer” in this day and age), cultural, intellectual and physical. Power is wielded directly or indirectly as a mixed bag of “hard” and “soft” attributes, a dichotomy that is well mentioned in the international relations and foreign policy literatures. Hybrid combinations of soft and hard power have led to “smart” and “sharp” power subsets depending on the emphasis given to one or the other basic trait.

The harder the exercise of power, the more coercive it is. Conversely, the more persuasive the way in which power is welded, the “softer” it is. Moreover, soft power can give way to hard power if the former is unsuccessful in accomplishing desired objectives, and soft power can be used as a follow up to the exercise of hard power. For example, “dollar diplomacy,” whereby large states fund development projects in small states on generous terms, is a form of soft power that can turn into hard power leverage once it becomes debt diplomacy in the form repayment conditions for those projects.

The exercise of State power has been institutionalized, codified and regulated over the years in a variety of contexts, including international relations and foreign policy. That is designed to strip inter-state relations of more overtly coercive approaches in favor of more consensus or compromise-oriented forms of engagement. However, in recent years the shift from a unipolar to a multipolar world-in-the-making has led to international norm erosion and a diminishing of international rule and law enforcement. That has produced a “back to the future” scenario where the international context has regressed to a modern version of the anarchic state of nature that Hobbes warned about in Leviathan. Emerging or restored great powers, particularly but not exclusively the PRC and Russia, have rejected international norms and laws in favor of a “might makes right” approach to international differences. Geopolitical coercion is at the heart of their international perspectives, which challenges the basic rules, norms and institutions of the liberal international order.

The turn towards more coercive forms of international politics is mirrored in the domestic politics of many States, including those led by democratic regimes. It is this–the emergence of coercive politics as a core feature of domestic and international governance–that is the focus of Ardern’s bifurcated foreign policy pronouncements in recent days. Her government understands that “liberal” governance is more than free and fair elections and respect for human rights. It is based on tolerance, compromise and mutual contingent consent between individuals, factions, parties and States.

Being unable to control the domestic regimes that govern States, Ardern’s bifurcated approach to NZ foreign policy (I would not call it a doctrine or anywhere close to one), is focused on countering coercive politics in international affairs. The general value principles of liberalism are upheld, but individual relations with other states, particularly important trade and security partners, are treated with a mix of value-based and pragmatic considerations, with pragmatism prevailing when strategic interests are at stake.

This approach allows NZ to broadly critique a trade partner’s human rights record while increasing or maintaining its trade with that partner in specific commodities under the argument that engagement with NZ’s values is better than isolation from them.

In other words, adherence in principle to liberal international values cloaks realistic assessments of where Aotearoa’s material interests are woven into the global institutional fabric. That may be cynical, hypocritical or short-sighted in its read of how the global order is evolving, but as a short-term diplomatic stance, it splits the difference between adherence to principle and amoral commitment to self-interested practice.

A Note of Caution.

The repeal of Roe vs Wade by the US Supreme Court is part of a broader “New Conservative” agenda financed by reactionary billionaires like Peter Thiel, Elon Mush, the Kochs and Murdochs (and others), organised by agitators like Steve Bannon and Rodger Stone and legally weaponised by Conservative (often Catholic) judges who are Federalist Society members. The agenda, as Clarence Thomas openly (but partially) stated, is to roll back the rights of women, ethnic and sexual minorities as part of an attempt to re-impose a heteronormative patriarchal Judeo-Christian social order in the US.

Worse, the influence of these forces radiates outwards from the US into places like NZ, where the rhetoric, tactics and funding of rightwing groups increasingly mirrors that of their US counterparts. Although NZ is not as institutionally fragile as the US, such foreign influences are corrosive of basic NZ social values because of their illiberal and inegalitarian beliefs. In fact, they are deliberately seditious in nature and subversive in intent. Thus, if we worry about the impact of PRC influence operations in Aotearoa, then we need to worry equally about these.

In fact, of the two types of foreign interference, the New Conservative threat is more immediate and prone to inciting anti-State and sectarian violence. Having now been established in NZ under the mantle of anti-vax/mask/mandate/”free speech” resistance, it is the 5th Column that needs the most scrutiny by our security authorities.

Media Link: “A View from Afar” on NATO and BRICS Leader’s summits.

Selwyn Manning and I discussed the upcoming NATO Leader’s summit (to which NZ Prime Minister Ardern is invited), the rival BRICS Leader’s summit and what they could mean for the Ruso-Ukrainian Wa and beyond.

Media Link: AVFA on Latin America.

In the latest episode of AVFA Selwyn Manning and I discuss the evolution of Latin American politics and macroeconomic policy since the 1970s as well as US-Latin American relations during that time period. We use recent elections and the 2022 Summit of the Americas as anchor points.

The PRC’s Two-Level Game.

Coming on the heels of the recently signed Solomon Islands-PRC bilateral economic and security agreement, the whirlwind tour of the Southwestern Pacific undertaken by PRC Foreign Minister Wang Yi has generated much concern in Canberra, Washington DC and Wellington as well as in other Western capitals. Wang and the PRC delegation came to the Southwestern Pacific bearing gifts in the form of offers of developmental assistance and aid, capacity building (including cyber infrastructure), trade opportunities, economic resource management, scholarships and security assistance, something that, as in the case of the Solomons-PRC bilateral agreement, caught the “traditional” Western patrons by surprise. With multiple stops in Kiribati, Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, PNG, Vanuatu and East Timor and video conferencing with other island states, Wang’s visit represents a bold outreach to the Pacific Island Forum community.

A couple of days ago I did a TV interview about the trip and its implications. Although I posted a link to the interview, I thought that I would flesh out was what unsaid in the interview both in terms of broader context as well as some of the specific issues canvassed during the junket. First, in order to understand the backdrop to recent developments, we must address some key concepts. Be forewarned: this is long.

China on the Rise and Transitional Conflict.

For the last three decades the PRC has been a nation on the ascent. Great in size, it is now a Great Power with global ambitions. It has the second largest economy in the world and the largest active duty military, including the largest navy in terms of ships afloat. It has a sophisticated space program and is a high tech world leader. It is the epicenter of consumer non-durable production and one of the largest consumers of raw materials and primary goods in the world. Its GDP growth during that time period has been phenomenal and even after the Covid-induced contraction, it has averaged well over 7 percent yearly growth in the decade since 2011.

The list of measures of its rise are many so will not be elaborated upon here. The hard fact is that the PRC is a Great Power and as such is behaving on the world stage in self-conscious recognition of that fact. In parallel, the US is a former superpower that has now descended to Great Power status. It is divided domestically and diminished when it comes to its influence abroad. Some analysts inside and outside both countries believe that the PRC will eventually supplant the US as the world’s superpower or hegemon. Whether that proves true or not, the period of transition between one international status quo (unipolar, bipolar or multipolar) is characterised by competition and often conflict between ascendent and descendent Great Powers as the contours of the new world order are thrashed out. In fact, conflict is the systems regulator during times of transition. Conflict may be diplomatic, economic or military, including war. As noted in previous posts, wars during moments of international transition are often started by descendent powers clinging or attempting a return to the former status quo. Most recently, Russia fits the pattern of a Great Power in decline starting a war to regain its former glory and, most importantly, stave off its eclipse. We shall see how that turns out.

Spheres of Influence.

More immediate to our concerns, the contest between ascendent and descendent Great Powers is seen in the evolution of their spheres of influence. Spheres of influence are territorially demarcated areas in which a State has dominant political, economic, diplomatic and military sway. That does not mean that the areas in question are as subservient as colonies (although they may include former colonies) or that this influence is not contested by local or external actors. It simply means at any given moment some States—most often Great Powers—have distinct and recognized geopolitical spheres of influence in which they have primacy of interest and operate as the dominant regional actor.

In many instances spheres of influence are the object of conquest by an ascendent power over a descendent power. Historic US dominance of the Western Hemisphere (and the Philippines) came at the direct expense of a Spanish Empire in decline. The rise of the British Empire came at the expense of the French and Portuguese Empires, and was seen in its appropriation of spheres of influence that used to be those of its diminished competitors. The British and Dutch spheres of influence in East Asia and Southeast Asia were supplanted by the Japanese by force, who in turn was forced in defeat to relinquish regional dominance to the US. Now the PRC has made its entrance into the West Pacific region as a direct peer competitor to the US.

Peripheral, Shatter and Contested Zones.

Not all spheres of influence have equal value, depending on the perspective of individual States. In geopolitical terms the world is divided into peripheral zones, shatter zones and zones of contestation. Peripheral zones are areas of the world where Great Power interests are either not in play or are not contested. Examples would be the South Pacific for most of its modern history, North Africa before the discovery of oil, the Andean region before mineral and nitrate extraction became feasible or Sub-Saharan Africa until recently. In the modern era spheres of influence involving peripheral zones tend to involve colonial legacies without signifiant economic value.

Shatter zones are those areas where Great Power interests meet head to head, and where spheres of influence clash. They involve territory that has high economic, cultural or military value. Central Europe is the classic shatter zone because it has always been an arena for Great Power conflict. The Middle East has emerged as a potential shatter zone, as has East Asia. The basic idea is that these areas are zones in which the threat of direct Great Power conflict (rather than via proxies or surrogates) is real and imminent, if not ongoing. Given the threat of escalation into nuclear war, conflict in shatter zones has the potential to become global in nature. That is a main reason why the Ruso-Ukrainian War has many military strategists worried, because the war is not just about Russia and Ukraine or NATO versus Russian spheres of influence.

In between peripheral and shatter zones lie zones of contestation. Contested zones are areas in which States vie for supremacy in terms of wielding influence, but short of direct conflict. They are often former peripheral zones that, because of the discovery of material riches or technological advancements that enhance their geopolitical value, become objects of dispute between previously disinterested parties. Contested zones can eventually become part of a Great Power’s sphere of influence but they can also become shatter zones when Great Power interests are multiple and mutually disputed to the point of war.

Strategic Balancing.

The interplay of States in and between their spheres of influence or as subjects of Great Power influence-mongering is at the core of what is known as strategic balancing. Strategic balancing is not just about relative military power and its distribution, but involves the full measure of a State’s capabilities, including hard, soft, smart and sharp powers, as it is brought to bear on its international relations.

That is the crux of what is playing out in the South Pacific today. The South Pacific is a former peripheral zone that has long been within Western spheres of influence, be they French, Dutch, British and German in the past and French, US and (as allies and junior partners) Australia and New Zealand today. Japan tried to wrest the West Pacific from Western grasp and ultimately failed. Now the PRC is making its move to do the same, replacing the Western-oriented sphere of influence status quo with a PRC-centric alternative.

The reason for the move is that the Western Pacific, and particularly the Southwestern Pacific has become a contested zone given technological advances and increased geopolitical competition for primary good resource extraction in previously unexploited territories. With small populations dispersed throughout an area ten times the size of the continental US covering major sea lines of communication, trade and exchange and with valuable fisheries and deep water mineral extraction possibilities increasingly accessible, the territory covered by the Pacific Island Forum countries has become a valuable prize for the PRC in its pursuit of regional supremacy. But in order to achieve this objective it must first displace the West as the major extra-regional patron of the Pacific Island community. That is a matter of strategic balancing as a prelude to achieving strategic supremacy.

Three Island Chains and Two Level Games.

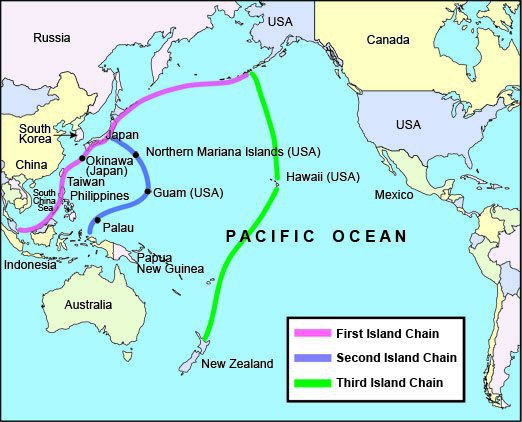

The core of the PRC strategy rests in a geopolitical conceptualization known as the “three island chains” This is a power projection perspective based on the PRC eventually gaining control of three imaginary chains of islands off of its East Coast. The first island chain, often referred to those included in the PRC’s “Nine Dash Line” mapping of the region, is bounded by Japan, Northwestern Philippines, Northern Borneo, Malaysia and Vietnam and includes all the waters within it. These are considered to be the PRC’s “inner sea” and its last line of maritime defense. This is a territory that the PRC is now claiming with its island-building projects in the South China Sea and increasingly assertive maritime presence in the East China Sea and the straits connecting them south of Taiwan.

The second island chain extends from Japan to west of Guam and north of New Guinea and Sulawesi in Indonesia, including all of the Philippines, Malaysian and Indonesian Borneo and the island of Palau. The third island chain, more aspirational than achievable at the moment, extends from the Aleutian Islands through Hawaii to New Zealand. It includes all of the Southwestern Pacific island states. It is this territory that is being geopolitically prepared by the PRC as a future sphere of influence, and which turns it into a contested zone.

(Source: Yoel Sano, Fitch Solutions)

The PRC approach to the Southwestern Pacific can be seen as a Two Level game. On one level the PRC is attempting to negotiate bilateral economic and security agreements with individual island States that include developmental aid and support, scholarship and cultural exchange programs, resource management and security assistance, including cyber security, police training and emergency security reinforcement in the event of unrest as well as “rest and re-supply” and ”show the flag” port visits by PLAN vessels. The Solomon Island has signed such a deal, and Foreign Minister Wang has made similar proposals to the Samoan and Tongan governments (the PRC already has this type of agreement in place with Fiji). The PRC has signed a number of specific agreements with Kiribati that lay the groundwork for a more comprehensive pact of this type in the future. With visits to Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and East Timor still to come, the approach has been replicated at every stop on Minister Wang’s itinerary. Each proposal is tailored to individual island State needs and idiosyncrasies, but the general blueprint is oriented towards tying development, trade and security into one comprehensive package.

None of this comes as a surprise. For over two decades the PRC has been using its soft power to cultivate friends and influence policy in Pacific Island states. Whether it is called checkbook or debt diplomacy (depending on whether developmental aid and assistance is gifted or purchased), the PRC has had considerable success in swaying island elite views on issues of foreign policy and international affairs. This has helped prepare the political and diplomatic terrain in Pacific Island capitals for the overtures that have been made most recently. That is the thrust of level one of this strategic game.

That opens the second level play. With a number of bilateral economic and security agreements serving as pillars or pilings, the PRC intends to propose a multinational regional agreement modeled on them. The first attempt at this failed a few days ago, when Pacific Island Forum leaders rejected it. They objected to a lack of detailed attention to specific concerns like climate change mitigation but did not exclude the possibility of a region-wide compact sometime in the future. That is exactly what the PRC wanted, because now that it has the feedback to its initial, purposefully vague offer, it can re-draft a regional pact tailored to the specific shared concerns that animate Pacific Island Forum discussions. Even if its rebuffed on second, third or fourth attempts, the PRC is clearly employing a “rinse, revise and repeat” approach to the second level aspect of the strategic game.

An analogy the captures the PRC approach is that of an off-shore oil rig. The bilateral agreements serve as the pilings or legs of the rig, and once a critical mass of these have been constructed, then an overarching regional platform can be erected on top of them, cementing the component parts into a comprehensive whole. In other words, a sphere of influence.

Western Reaction: Knee-Jerk or Nuanced?

The reaction amongst the traditional patrons has been expectedly negative. Washington and Canberra sent off high level emissaries to Honiara once the Solomon Islands-PRC deal was leaked before signature, in a futile attempt to derail it. The newly elected Australian Labor government has sent its foreign minister, sworn into office under urgency, twice to the Pacific in two weeks (Fiji, Tonga and Samoa) in the wake of Minister Wang’s visits. The US is considering a State visit for Fijian Prime Minister (and former dictator) Frank Baimimarama. The New Zealand government has warned that a PRC military presence in the region could be seriously destabilising and signed on to a joint US-NZ statement at the end of Prime Minister Ardern’s trade and diplomatic junket to the US re-emphasising (and deepening) the two countries’ security ties in the Pacific pursuant to the Wellington and Washington Agreements of a decade ago.

The problem with these approaches is two-fold, one general and one specific. If countries like New Zealand and its partners proclaim their respect for national sovereignty and independence, then why are they so perturbed when a country like the Solomon Islands signs agreements with non-traditional patrons like the PRC? Besides the US history of intervening in other countries militarily and otherwise, and some darker history along those lines involving Australian and New Zealand actions in the South Pacific, when does championing of sovereignty and independence in foreign affairs become more than lip service? Since the PRC has no history of imperialist adventurism in the South Pacific and worked hard to cultivate friends in the region with exceptional displays of material largesse, is it not a bit neo-colonial paternalistic of Australia, NZ and the US to warn Pacific Island states against engagement with it? Can Pacific Island states not find out themselves what is in store for them should they decide to play the Two Level Game?

More specifically, NZ, Australia and the US have different security perspectives regarding the South Pacific. The US has a traditional security focus that emphasises great power competition over spheres of influence, including the Western Pacific Rim. It has openly said that the PRC is a threat to the liberal, rules-based international order (again, the irony abounds) and a growing military threat to the region (or at least US military supremacy in it). As a US mini-me or Deputy Sheriff in the Southern Hemisphere, Australia shares the US’s traditional security perspective and emphasis when it comes to threat assessments, so its strategic outlook dove-tails nicely with its larger 5 Eyes partner.

New Zealand, however, has a non-traditional security perspective on the Pacific that emphasises the threats posed by climate change, environmental degradation, resource depletion, poor governance, criminal enterprise, poverty and involuntary migration. As a small island state, NZ sees itself in a solidarity position with and as a champion of its Pacific Island neighbours when it comes to representing their views in international fora. Yet it is now being pulled by its Anglophone partners into a more traditional security perspective when it comes to the PRC in the Pacific, something that in turn will likely impact on its relations with the Pacific Island community, to say nothing of its delicate relationship with the PRC.

In any event, the Southwestern Pacific is a microcosmic reflection of an international system in transition. The issue is whether the inevitable conflicts that arise as rising and falling Great Powers jockey for position and regional spheres of influence will be resolved via coercive or peaceful means, and how one or the other means of resolution will impact on their allies, partners and strategic objects of attention such as the Pacific Island community.

In the words of the late Donald Rumsfeld, those are the unknown unknowns.

Something on NZ military diplomacy.

A few weeks ago it emerged that NZ Minister of Defence Peeni Henare had asked cabinet for approval to donate surplus NZDF Light Armoured Vehicles (LAVs) to Ukraine as part of the multilateral efforts to support the Ukrainian defence of its homeland against the Russian invasion that is now into its sixth week. A key to Ukrainian success has been the logistical resupply provided by NATO members, NATO partners (who are not NATO members) such as Australia, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand (which has sent signals/technical intelligence officers, non-lethal military and humanitarian aid and money for weapons purchases to the UK and NATO Headquarters in Brussels for forward deployment). This includes lethal as well as non-lethal military supplies and humanitarian aid for those disposed and dislocated by the war (nearly 6 million Ukrainians have left the country, in the largest refuge flow in Europe since WW2).

Cabinet rejected the request, which presumably had the approval of the NZDF command before it was sent to the Minister’s desk. There has been speculation as to why the request was rejected and true to form, National, ACT and security conservatives criticised the move as more evidence of Labour’s weakness on security and intelligence matters. Conversely, some thought that the current level and mix of aid provided is sufficient. At the time I opined that perhaps Labour was keeping its powder dry for a future reconsideration or as a means of setting itself up as a possible interlocutor in a post-conflict negotiation scenario. Others were, again, less charitable when it comes to either the military or diplomatic logics at play.

Whatever the opinion about the cabinet decision to not send LAVs to Ukraine at this moment, we should think of any offer to contribute to the Ukrainian defence as a form of military diplomacy. As a NATO partner NZ was duty-bound to contribute something, even if as a token gesture of solidarity. Its material contributions amount to around NZ$30million, a figure that is dwarfed by the monetary contributions of the other three NATO partners, which total over NZ$100 million each. Japan and South Korea have not contributed lethal aid, focusing on non-lethal military supplies akin to those sent by the NZDF and humanitarian aid similar to that provided by NZ, but on much larger scale. In addition to its material contributions, NZ has 64 civilian and military personnel deployed in Europe as part of its Ukrainian support effort; Japan and South Korea have none (as far as is known). Australia has sent 20 Bushmaster armoured personnel carriers and military aid worth A$116 million, plus A$65 million in humanitarian aid. The number of Australian personnel sent has not been disclosed.

In this context, it is worth re-examining the question of whether surplus NZDF LAVs should be considered for donation to Ukraine. First, a summary of what they are.

The NZDF LAVs are made in Canada by General Dynamics Land Systems. The NZDF version are LAV IIIs (third generation) that were purchased to replace the old MII3 armoured personnel vehicles. Unlike the MII3s, the LAVs are 8-wheeled rather than tracked, making them unsuitable for sandy, swampy or boggy terrain but ideal for high speed (up to 100KPH) deployment on hard dirt tracks or paved roads. It carries 6-8 troops and a crew of three. It has a turret chain gun and secondary weapons systems, but needs to be up armoured in most combat situations that do not involve high speed incursions behind heavy armour (such as mounted or dismounted infantry rifleman patrols) A contract was let for the purchase of 105 units in 2001 by the 5th Labour Government fronted by its Defense Minister Mark Burton, and the bulk of the purchase were delivered by the end of 2004. Criticism rained in from all sides (including from me) that the LAVs were unsuited for the Pacific Region where they would most likely be deployed, and that the two battalion motorised infantry force envisioned by the Army (that would use all 105 LAVs) was unrealistic at best. Subsequent audits questioned the rational and extent of the purchase, but no action was taken to reverse it.

The NZDF LAVs saw action in Afghanistan as SAS support vehicles and later as infantry patrol vehicles in Bamiyan Province. A total of 8 were deployed, with one being destroyed by an IED. Two were deployed to the Napier police shootings in 2009, two were deployed to a siege in Kawerau in 2016 and several were deployed to Christchurch as post-earthquake security patrol vehicles in 2011. That is the extent of their operational life. The majority of the fleet are stationed/stored at Camp Waiouru, Camp Trentham and Camp Burnham. That brings us to their current status.

NZ Army has +/- 103 LAVs in inventory (besides the destroyed vehicle two are used for parts). It reportedly can crew +/- 40 LAVs max ( a total that includes vehicle operators and specialised mechanics). It has sold 22 to Chile with 8 more on sale. NZ bought the LAVs for +/-NZ$6.22 million/unit and it sold to the Chilean Navy for +/- NZ$902,270/unit. It may keep a further 3 for parts, leaving 70 in inventory. That leaves +/- 30 to spare if my figures are correct. NZDF says it needs all remaining +/-70 LAVs, which is aspirational, not practical, especially since the Army contracted to purchase 43 Australian-made Bushmaster APCs in 2020 that are designed to supplement, then replace the LAVs as they reach retirement age.

That makes the NZDF insistence on retaining 70 LAVs somewhat puzzling. Does it expect to eventually sell off all the long-mothballed and antiquated vehicles (LAVs are now into the fourth and fifth generation configurations) at anything more than pennies for dollars? Given strategic export controls, to whom might the LAVs be sold? Of those who would be acceptable clients (i.e. non-authoritarian human rights-abusing regimes) who would buy used LAVIIIs when newer versions are available that offer better value for money?

With that in mind, practicality would advise the MoD/NZDF to donate them to Ukraine even if, in the interest of diplomatic opacity, the LAVs are sent to a NATO member that can withstand Russian pressure to refuse the donation on behalf of the Ukrainians (say, Poland, Rumania or even Canada, which already has a large LAV fleet). From there the LAVs can be prepared for re-patriation to Ukraine. There can be other creative options explored with like-minded states that could involve equipment swaps or discounted bulk purchases and sales that facilitate the transit of the NZ LAVs to Ukrainian military stores in exchange for supplying NZDF future motorised/armoured requirements. The probabilities may not be infinite but what is practicable may be broader than what seems immediately possible.

Rest assured that the Ukrainians can use the LAVs even if they are +20 years old, need up-armouring and need to be leak-proofed to do serious water crossings (does the Chilean Navy and its Marines know this?). But the main reason for donating them is that the diplomatic benefit of the gift out-weighs its (still significant) military value. That is because NZ will be seen to be fully committed to putting its small but respected weight behind multilateral efforts to reaffirm the norm-based International order rather than just pay lip service to it. To be clear, even if making incremental gains in the Dombas region using scorched earth tactics, the military tide has turned against the Russians. Foreign weapons supplies are a big part of that, so the moment to join extant efforts seems favourable to NZ’s diplomatic image. The saying that diplomacy is cowardice masquerading as righteous principle might apply here but the immediate point is that by stepping up its contribution of “defensive” weapons to Ukraine (as all donated weapons systems are characterised), NZ will reap diplomatic benefits immediately and down the road.

As for the Russians. What can they do about it? Their means of retaliation against NZ are few and far between even if cyber warfare tactics are used against NZ targets. NZ has already levied sanctions against Russian citizens and companies in accordance with other Western democracies, so adding LAVs into the punitive mix is not going to significantly tilt the Russian response into something that NZ cannot withstand.

Given all of this, Cabinet may want to re-consider the NZDF desire to contribute to its NATO partner’s request above what has been offered so far. Unless there are hidden factors at play, gifting surplus LAVs to the defense of Ukrainian independence would be a reasonable way to do so. The practical questions are how to get them there (since RNZAF airlift capability realistically cannot) and how to get them in combat-ready condition in short order so those who can carry them to the war zone can use them immediately. Rather then let them rust in NZ waiting to be called into improbable service or waiting for a sale that is likely to never happen, the possibility of donating LAVs to the Ukrainian cause is worth more thought.

A word on post-neoliberalism.

I recently read a critique of the market-oriented economic theory known as “neoliberalism” and decided to add some of my thoughts about it in a series of short messages on a social media platform dedicated to providing an outlet for short messaging. I have decided to expand upon those messages and provide a slightly more fleshed out appraisal here.

“Neoliberalism” has gone from being a monetarist theory first mentioned in academic circles about the primacy of finance capital in the pyramid of global capitalism to a school of economic thought based on that theory, to a type of economic policy (via the Washington consensus) promoted by international financial institutions to national governments, to a broad public policy framework grounded in privatisation, low taxation and reduction of public services, to a social philosophy based on reified individualism and decontextualised notions of freedom of choice. Instilled in two generations over the last 35-40 years, it has redefined notions of citizenship, collective and individual rights and responsibilities (and the relationship between them) in liberal democracies, either long-standing or those that emerged from authoritarian rule in the period 1980-2000.

That was Milton Friedman’s ultimate goal: to replace societies of rent-seekers under public sector macro-managing welfare states with a society of self-interested maximizers of opportunities in an environment marked by a greatly reduced state presence and unfettered competition in all social (economic, cultural, political) markets. It may not have been full Ayn Rand in ideological genesis but the social philosophy behind neoliberalism owes a considerable debt to it.

What emerged instead was societies increasingly marked by survivalist alienation rooted in feral capitalism tied to authoritarian-minded (or simply authoritarian) neo-populist politics that pay lip service to but do not provide for the common good–and which do not adhere to the original neoliberal concept in theory or in practice. Survivalist alienation is (however inadvertently) encouraged and compounded by a number of pre- and post-modern identifications and beliefs, including racism, xenophobia, homophobia and social media enabled conspiracy theories regarding the nature of governance and the proper (“traditional” versus non-traditional) social order. This produces what might be called social atomisation, a pathology whereby individuals retreat from horizontal solidarity networks and organisations (like unions and volunteer service and community agencies) in order to improve their material, political and/or cultural lot at the expense of the collective interest. As two sides of neoliberal society, survivalist alienation and social atomisation go hand-in-hand because one is the product of the other.

That is the reality that right-wingers refuse to acknowledge and which the Left must address if it wants to serve the public good. The social malaise that infects NZ and many other formally cohesive democratic societies is more ideological than anything else. It therefore must be treated as such (as the root cause) rather than as a product of the symptoms that it displays (such as gun violence and other anti-social behaviours tied to pathologies of income inequality such as child poverty and homelessness).

As is now clear to most, neoliberalism is dead in any of the permutations mentioned above. And yet NZ is one of the few remaining democratic countries where it is still given any credence. Whether it be out of wilful blindness or cynical opportunism, business elites and their political marionettes continue to blather about the efficiencies of the market even after the Covid pandemic has cruelly exposed the deficiencies and inequalities of global capitalism constructed on such things as “just in time production” and “debt leveraged financing” (when it comes to business practices) and “race to the bottom” when it comes wages (from a labour market perspective).

I shall end this brief by starting at the beginning by way of an anecdote. As I was trying to explain “trickle down” economic theory to an undergraduate class in political economy, a student shouted from the back seats of the lecture hall “from where I sit, it sure sounds more like the “piss on us” theory.

I could not argue with that view then and I can’t argue with it now. Except today things are much worse because the purine taint is not limited to an economic theory that has run its course, but is pervasive in the fabric of post-neoliberal societies. Time for a deep clean.

PS: For those with the inclination, here is something I wrote two decades ago on roughly the same theme but with a different angle. Unfortunately it is paywalled but the first page is open and will allow readers a sense of where I was going with it.

Media Link: AVFA on small state approaches to multilateral conflict resolution in transitional times.

In this week’s “A View from Afar” podcast Selwyn Manning and I used NZ’s contribution of money to purchase weapons for Ukraine as a stepping stone into a discussion of small sate roles in coalition-building, multilateral approaches to conflict resolution and who and who is not aiding the effort to stem the Russian invasion. We then switch to a discussion of the recently announced PRC-Solomon Islands security agreement and the opposition to it from Australia, NZ and the US. As we note, when it comes to respect for sovereignty and national independence in foreign policy, in the cases of Ukraine and the Solomons, what is good for the goose is good for the gander.

We got side-tracked a bit with a disagreement between us about the logic of nuclear deterrence as it might or might not apply to the Ruso-Ukrainian conflict, something that was mirrored in the real time on-line discussion. That was good because it expanded the scope of the storyline for the day, but it also made for a longer episode. Feel free to give your opinions about it.