Recent NACTFirst government assaults on female pay equity, public sector employment, labour regulations and other worker’s rights (to say nothing of trying to roll back Maori Treaty rights and enshrine the primacy of property right in NZ law), got me to thinking about how we measure value and worth in society. I tend to think of society being made of contributors and freeloaders. Contributors add value to their communities, be they large or small. They can be paid or unpaid, employed or volunteers, able-bodied or disabled. To me, these people are of high value and therefore of high worth. Freeloaders, on the other hand, are those who ride on the backs of others’ contributions. They can be criminals or hedge fund managers, financial advisors and consultants, rightwing bloggers and conspiracy theorists, gossip columnists or politicians. They do not create value in or for society. They appropriate worth when they can by appraising and selling themselves for more than their real value.

To be clear, this measure is not about surplus value in production and by whom it is appropriated. It is about the relationship between real value and actual worth, which may or may not be related.

Three illustrations of the spurious relationship of value and worth come to mind. There is an old saying in Latin America that a great bargain is to buy a person for their real value and then sell them for what they say they are worth. On another front, someone I know runs a financial advisory service where he caters to what he initially called “high value people.” When it was pointed out to him that he was conflating material worth with human value, he changed his firm’s logo but we have not had a good relationship since (he caters to clients with disposable investment assets of USD 10 million or more, including professional athletes). In a similar but opposite vein, my late mother, an organic intellectual if there ever was one, used to say that our wage scales are completely upside down. We should pay rubbish collectors and sewer cleaners the highest salaries and pay professional athletes and entertainers the minimum wage. Her reasoning was that athletes and entertainers provide some value to society but will receive many more benefits, material and otherwise, from the public adulation that they engender, and they will receive these benefits long after their active careers are done. Their material worth far exceeds their social value.

Conversely, those who do what in India is considered Untouchable work are essential to the good functioning of modern society and in fact critical to maintaining public health and well-being. Because of the nature of their work and the negative exposures involved in it, their careers are short and often brutish. And yet in modern society the reverse is true when it comes to their value and worth. They are paid far less (as a measure of worth) than their actual value to society. Why is that? Even if we factor in things like education, entrepreneurship and other intervening variables and admit for the existence of objectively fair measures of value and worth (and by this I do not mean the stupid comparisons of nurses and teachers versus cops and firefighter’s pay or any other gendered work comparisons), it seems that oftentimes the relationship between actual societal value and perceived worth is perversely skewed in inversely proportional ways.

That brings me back to the secondary teacher’s strike this past week. Although I left academia over a decade ago before the academic Taylorists turned universities into scholastic sweatshops whose focus is on revenue generation rather than intellectual advancement, and who believe that Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (now sometimes replaced by “Economics and Management” as the back end of the “STEM” mantra) should be the sole focus of university research and teaching (eliminating the Arts and Social Sciences), I maintain contacts with a number of academics who have managed to keep their jobs and still pursue the life of the mind while teaching within the limits of current Taylorist curriculum paradigms and business models.

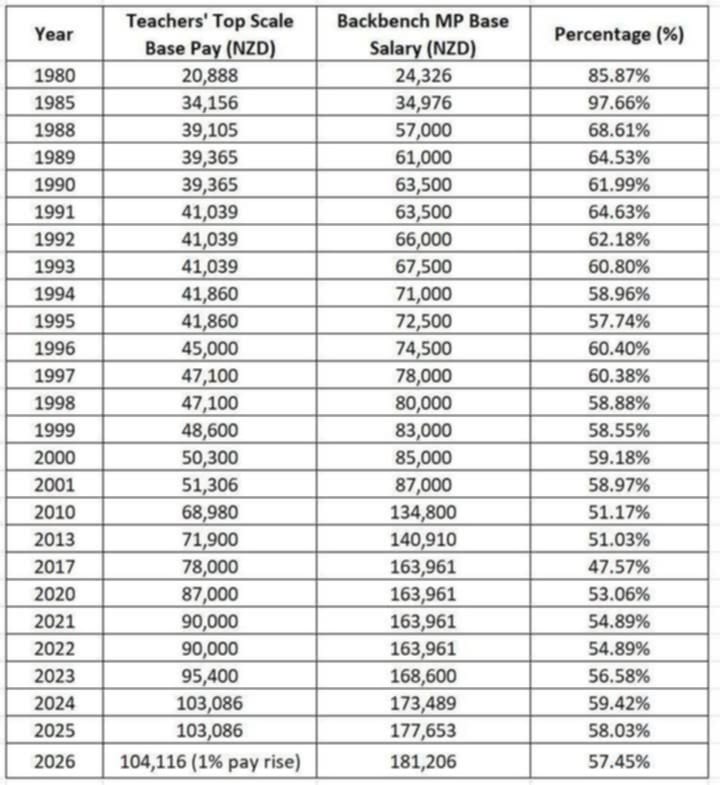

One of these contacts has just been made redundant by the NZ university to which they are affiliated (which is in the process of dismantling its social science programs while still recruiting students for admission in to them), so is considering turning to secondary school teaching as a new career path. They are also thinking about working in a policy analyst role, including in a parliamentary or political party setting. As part of the research and preparation process for that transition, and in light of the current stand-off between the government and secondary teacher’s union about cost-of-living (COLA) wage increases, they reached out to fellow colleagues who do research on related subjects in order to get a comparative idea of wages in those career fields. Although there are a number of interesting facts that came from the materials that my contact received that are worth discussing at another time, this one was shared with me. It involves the comparative base remuneration of backbench MPs and the upper end of teacher’s pay scales.

The data begs some questions. Who brings more value to NZ society, MPs or teachers? How is their value measured? What is worth more to NZ society, politicians or teachers? How is their (comparative) worth measured? Comparatively speaking, in terms of their contributions to NZ society, who is valued more and who is worth more? More broadly, is there a relationship between value and worth in NZ?

As for the specifics of the chart. Why is is the worth of backbench MPs (as measured in wages) significantly higher than that of the most experienced and well paid teachers? Since MPs also receive non-wage benefits such as accomodation and travel allowances and are often “comped” by lobbyists and other interlocutors in the form of meals and other incidentals, why is the wage gap between them and the most experienced teachers so significant? As for work equivalence, it can be argued that both MPs and teachers work long hours beyond their assigned time in class or in the parliament debating chamber, and both sacrifice family life and other leisure pursuits in order to do so. Both have formal work hours and yet engage in much informal work (say, coaching sports teams or participating in civic groups). Both MPs and teachers have invested much time and resources into their own educations and qualifications as well as through practical experience. So why the difference in worth if their value to society is similar if not equal? Or is their value not equal and hence their worth simply reflects the difference?

That last question is key. Does NZ society value MPs more than teachers and thus pay them more as a measure of their worth? Admitting for a degree of autonomy in setting institutional wage standards, are the average parliamentarians worth that much more than the most experienced teachers? Is their comparative worth–and that of teachers–based on any measure of value?

Perhaps there is a market-based answer to the question such as “politicians are rare gems that are hard to find while teachers are a dime a dozen because they are like pebbles on a beach, etc.” But even if this were true, perhaps scarcity of a resource is not a true measure of value. Memecoins such as $TRUMP may be worth much (+USD8.36/coin with a market cap of over USD 1.6 billion) but do they have any intrinsic or tangible value?

I will leave it for readers to ponder these questions and the more general question about the relationship of social value and material worth. However, one thing should be clear. Only when that relationship is defined and put into practice can we begin to speak of working towards a fair and equitable democratic capitalist society.