Background

Background

The Pirate Bay is a BitTorrent tracker – one of the world’s largest, most popular and best-known. Four of its co-founders were yesterday convicted of “assisting in making copyright content available”, sentenced to 12 months’ jail each and required to pay 30 million Kronor (about NZ$6.3m) between them. The offence was not the same as actually distributing the copyright material – the torrent files hosted on TPB are not themselves subject to copyright, but they enable a user to easily access material which is. For a quick backgrounder, see The Guardian’s FAQ, and for exhaustive coverage, see Threat Level’s archive.

I’m very interested indeed in the roles which intellectual property mechanisms play in the world. This verdict has complex and possibly profound political, social, technological and economic implications. I won’t argue its legal merits, but, despite their claims, I don’t think this case or verdict is in the content owners’ best long-term interests, because it perpetuates a business model which has been proven unfit for its purpose.

Social and political implications

Social and political implications

The social and political implications of this verdict seem likely to result in a sort of Streisand effect where by winning a battle, copyright owners may galvanise opposition to their business model and enforcement practices. This verdict was never going to be the end; as defendant Peter Sunde said it was to decide nothing other than which side would file an appeal. [Video in two parts here and here. The first five minutes or so is in Swedish; the rest is in English.] So as much bad-will as there is against the content owners, there’s plenty more time for it to build.

Online media consumption (sanctioned and otherwise) is largely the domain of the two generations born since the baby boom – quite distinct from those in control of the legal, business and political systems which produce that media and constrain its usage, who are middle-aged and older. There exists a significant disconnect between these generations, and the Pirate Bay verdict seems like it could crystallise that disconnect into an outright generational divide along political and philosophical lines. Those in their thirties and forties have been heavily involved in shaping the internet into the phenomenon it is, nurturing fledgling technologies (including filesharing) to meet their own needs and building cultures and identities around different types of participation. It’s theirs; they created it. The generation now in their teens and twenties have known nothing else, and they are the driving force behind its constant recreation, and are if anything even more strongly engaged. The content industry is currently trying the ‘stick’ approach – trying to dictate terms to two generations who’re used to having things their way and are more than capable of making it so. As those generations displace their pre-internet elders, and as the developing world begins to participate more strongly in traditionally-Western information communities, content owners will find themselves less able to dictate terms, not more so. Those in charge of intellectual property realise this and have been busy over the past few decades establishing and extending copyright, patent and trademark systems, conditional trade treaties, anti-circumvention legislation, privacy infringements under the guise of cyber-terrorism prevention, and other such measures under the auspices of TRIPS, the DMCA, the PATRIOT Act, IPRED and plenty of lawsuits, including this one – all in order to retain their existing, inferior business models rather than be forced to compete on the open market of ideas in order to develop better ones.

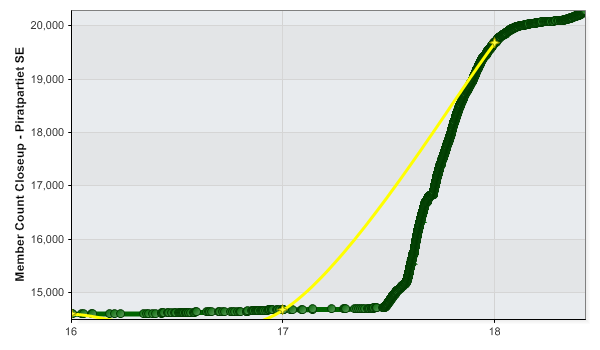

There are political implications for all of this, as well Рthe Pirate Party of Sweden, formed to reform copyright law, abolish the patent system and strengthen privacy rights, claims to have gained 3,000 new members in the seven hours following the verdict, giving it a larger membership than four out of seven current parties in the Swedish parliament (and if their online membership graph can be believed, it looks like they were up above 5,000 new members within 12 hours). Candidate Christian Engstr̦m said:

There are political implications for all of this, as well Рthe Pirate Party of Sweden, formed to reform copyright law, abolish the patent system and strengthen privacy rights, claims to have gained 3,000 new members in the seven hours following the verdict, giving it a larger membership than four out of seven current parties in the Swedish parliament (and if their online membership graph can be believed, it looks like they were up above 5,000 new members within 12 hours). Candidate Christian Engstr̦m said:

“The ruling is our ticket to the European Parliament,†concluded Engström, who expects a populist backlash against the ruling to help his party’s chances of gaining a seat in the EU’s primary legislative body. [source]

Now, single-issue parties have a particularly hard row to hoe (even TPB’s Peter Sunde doesn’t vote for the Pirate Party), and in terms of realpolitik few countries can afford to deviate from the intellectual property line established by TRIPS. Nevertheless there are big philosophical issues at stake here. Politicians ignore those two generations at their peril.

Technological and economic implications

Technological and economic implications are linked because technology dictates the means by which content may be distributed, and without distribution there is no revenue. The Streisand effect mentioned above will likely manifest initially in the market for media as a short-term (and possibly short-lived) , but its long-term implications are much broader. Many of the content owners’ arguments against groups like TPB rest on the flawed premise that demand for content is static and copyright infringement is zero-sum (that is: every copy downloaded represents one less copy bought). The fall in revenue, they claim, is because of copyright infringement, so reducing copyright infringement will necessarily cause revenue to pick up again. There are two problems here: first, the genie is already out of the bottle, and two generations are now accustomed to consuming media on their own terms. They will not be forced to consume media in only the ways which content owners want them to, and whoever applies the stick in an attempt to make them do so will suffer as a consequence, because the content industries depend upon their consumers for survival, not the other way around. Second, and this is critical: by engaging in an aggressive game of whack-a-mole to safeguard a broken business model, the content industry has hastened the destruction of that business model by ensuring that only the fittest filesharing systems survive. Cory Doctorow makes both points better than I:

If The Pirate Bay shuts down, it’s certain that something else will spring up in its wake, of course — just as The Pirate Bay appeared in the wake of the closure of other, more “moderate” services.

With each successive takedown, the entertainment industry forces these services into architectures that are harder to police and harder to shut down. And with each takedown, the industry creates martyrs who inspire their users into an ideological opposition to the entertainment industry, turning them into people who actively dislike these companies and wish them ill (as opposed to opportunists who supplemented their legal acquisition of copyrighted materials with infringing downloads).

It’s a race to turn a relatively benign symbiote (the original Napster, which offered to pay for its downloads if it could get a license) into vicious, antibiotic resistant bacteria that’s dedicated to their destruction.

Content owners, by enforcing the discipline required to survive in a hostile environment, are granting clandestine distribution systems an enormous advantage: those systems evolve and improve while their own system stagnates. There are a few exceptions: Radiohead and Trent Reznor are at the forefront.

Of much more grave seriousness, however, is the chilling effect this verdict could have on the internet – search engines, ISPs and end users. Roger Wallis, Emeritus Professor of Media at Sweden’s Royal Institute of Technology (and an expert witness for the defence) warned:

This will cause a flood of court cases. Against all the ISPs. Because if these guys assisted in copyright infringements, then the ISPs also did. This will have huge consequences. The entire development of broadband may be stalled.

His point is that TPB’s technology meant their servers never hosted copyright files – those were hosted on its users’ home computers, and TPB simply provides a search engine to find content and a service which tells one user’s computer where to find files hosted on another user’s computer. If that makes one criminally liable, then those who are doing the actual distribution (te end users) and a whole lot of other people and organisations whose computers provide similar assistance including search engines and ISPs, are also criminally liable – and could even be more culpable than TPB were, since those computers actually host and distribute the copyright files themselves. Due to the highly robust, distributed, fault-tolerant nature of modern content-distribution systems made fit by nearly a decade’s worth of fine-tuning, there is simply no way to beat filesharing without targeting end-users and ISPs on a case-by-case basis. Any reluctance to roll out or use broadband internet services will have catastrophic flow-on economic effects, and given that media consumption is a major driver of broadband, content owners are in a catch-22 situation: either they aggressively prosecute ISPs and end-users or they fail to beat filesharing. In the former case, they get to keep their business model, at the cost of making criminals of their consumer base and ensuring that yet more complex, robust and powerful distribution mechanisms are developed – and possibly at the cost of the internet as we know it. In the latter case, they have to develop systems which are fit enough to survive on their own. The longer they delay, the harder it will be.

An upcoming post will look at the battle for hearts and minds which will fundamentally determine the winner in this contest.

L