In the latest episode of AVFA Selwyn Manning and I discuss the evolution of Latin American politics and macroeconomic policy since the 1970s as well as US-Latin American relations during that time period. We use recent elections and the 2022 Summit of the Americas as anchor points.

The PRC’s Two-Level Game.

Coming on the heels of the recently signed Solomon Islands-PRC bilateral economic and security agreement, the whirlwind tour of the Southwestern Pacific undertaken by PRC Foreign Minister Wang Yi has generated much concern in Canberra, Washington DC and Wellington as well as in other Western capitals. Wang and the PRC delegation came to the Southwestern Pacific bearing gifts in the form of offers of developmental assistance and aid, capacity building (including cyber infrastructure), trade opportunities, economic resource management, scholarships and security assistance, something that, as in the case of the Solomons-PRC bilateral agreement, caught the “traditional” Western patrons by surprise. With multiple stops in Kiribati, Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, PNG, Vanuatu and East Timor and video conferencing with other island states, Wang’s visit represents a bold outreach to the Pacific Island Forum community.

A couple of days ago I did a TV interview about the trip and its implications. Although I posted a link to the interview, I thought that I would flesh out was what unsaid in the interview both in terms of broader context as well as some of the specific issues canvassed during the junket. First, in order to understand the backdrop to recent developments, we must address some key concepts. Be forewarned: this is long.

China on the Rise and Transitional Conflict.

For the last three decades the PRC has been a nation on the ascent. Great in size, it is now a Great Power with global ambitions. It has the second largest economy in the world and the largest active duty military, including the largest navy in terms of ships afloat. It has a sophisticated space program and is a high tech world leader. It is the epicenter of consumer non-durable production and one of the largest consumers of raw materials and primary goods in the world. Its GDP growth during that time period has been phenomenal and even after the Covid-induced contraction, it has averaged well over 7 percent yearly growth in the decade since 2011.

The list of measures of its rise are many so will not be elaborated upon here. The hard fact is that the PRC is a Great Power and as such is behaving on the world stage in self-conscious recognition of that fact. In parallel, the US is a former superpower that has now descended to Great Power status. It is divided domestically and diminished when it comes to its influence abroad. Some analysts inside and outside both countries believe that the PRC will eventually supplant the US as the world’s superpower or hegemon. Whether that proves true or not, the period of transition between one international status quo (unipolar, bipolar or multipolar) is characterised by competition and often conflict between ascendent and descendent Great Powers as the contours of the new world order are thrashed out. In fact, conflict is the systems regulator during times of transition. Conflict may be diplomatic, economic or military, including war. As noted in previous posts, wars during moments of international transition are often started by descendent powers clinging or attempting a return to the former status quo. Most recently, Russia fits the pattern of a Great Power in decline starting a war to regain its former glory and, most importantly, stave off its eclipse. We shall see how that turns out.

Spheres of Influence.

More immediate to our concerns, the contest between ascendent and descendent Great Powers is seen in the evolution of their spheres of influence. Spheres of influence are territorially demarcated areas in which a State has dominant political, economic, diplomatic and military sway. That does not mean that the areas in question are as subservient as colonies (although they may include former colonies) or that this influence is not contested by local or external actors. It simply means at any given moment some States—most often Great Powers—have distinct and recognized geopolitical spheres of influence in which they have primacy of interest and operate as the dominant regional actor.

In many instances spheres of influence are the object of conquest by an ascendent power over a descendent power. Historic US dominance of the Western Hemisphere (and the Philippines) came at the direct expense of a Spanish Empire in decline. The rise of the British Empire came at the expense of the French and Portuguese Empires, and was seen in its appropriation of spheres of influence that used to be those of its diminished competitors. The British and Dutch spheres of influence in East Asia and Southeast Asia were supplanted by the Japanese by force, who in turn was forced in defeat to relinquish regional dominance to the US. Now the PRC has made its entrance into the West Pacific region as a direct peer competitor to the US.

Peripheral, Shatter and Contested Zones.

Not all spheres of influence have equal value, depending on the perspective of individual States. In geopolitical terms the world is divided into peripheral zones, shatter zones and zones of contestation. Peripheral zones are areas of the world where Great Power interests are either not in play or are not contested. Examples would be the South Pacific for most of its modern history, North Africa before the discovery of oil, the Andean region before mineral and nitrate extraction became feasible or Sub-Saharan Africa until recently. In the modern era spheres of influence involving peripheral zones tend to involve colonial legacies without signifiant economic value.

Shatter zones are those areas where Great Power interests meet head to head, and where spheres of influence clash. They involve territory that has high economic, cultural or military value. Central Europe is the classic shatter zone because it has always been an arena for Great Power conflict. The Middle East has emerged as a potential shatter zone, as has East Asia. The basic idea is that these areas are zones in which the threat of direct Great Power conflict (rather than via proxies or surrogates) is real and imminent, if not ongoing. Given the threat of escalation into nuclear war, conflict in shatter zones has the potential to become global in nature. That is a main reason why the Ruso-Ukrainian War has many military strategists worried, because the war is not just about Russia and Ukraine or NATO versus Russian spheres of influence.

In between peripheral and shatter zones lie zones of contestation. Contested zones are areas in which States vie for supremacy in terms of wielding influence, but short of direct conflict. They are often former peripheral zones that, because of the discovery of material riches or technological advancements that enhance their geopolitical value, become objects of dispute between previously disinterested parties. Contested zones can eventually become part of a Great Power’s sphere of influence but they can also become shatter zones when Great Power interests are multiple and mutually disputed to the point of war.

Strategic Balancing.

The interplay of States in and between their spheres of influence or as subjects of Great Power influence-mongering is at the core of what is known as strategic balancing. Strategic balancing is not just about relative military power and its distribution, but involves the full measure of a State’s capabilities, including hard, soft, smart and sharp powers, as it is brought to bear on its international relations.

That is the crux of what is playing out in the South Pacific today. The South Pacific is a former peripheral zone that has long been within Western spheres of influence, be they French, Dutch, British and German in the past and French, US and (as allies and junior partners) Australia and New Zealand today. Japan tried to wrest the West Pacific from Western grasp and ultimately failed. Now the PRC is making its move to do the same, replacing the Western-oriented sphere of influence status quo with a PRC-centric alternative.

The reason for the move is that the Western Pacific, and particularly the Southwestern Pacific has become a contested zone given technological advances and increased geopolitical competition for primary good resource extraction in previously unexploited territories. With small populations dispersed throughout an area ten times the size of the continental US covering major sea lines of communication, trade and exchange and with valuable fisheries and deep water mineral extraction possibilities increasingly accessible, the territory covered by the Pacific Island Forum countries has become a valuable prize for the PRC in its pursuit of regional supremacy. But in order to achieve this objective it must first displace the West as the major extra-regional patron of the Pacific Island community. That is a matter of strategic balancing as a prelude to achieving strategic supremacy.

Three Island Chains and Two Level Games.

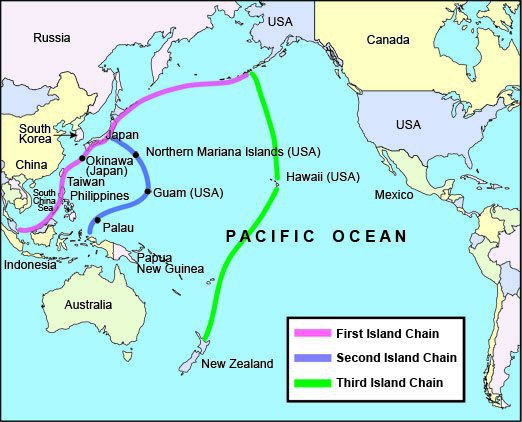

The core of the PRC strategy rests in a geopolitical conceptualization known as the “three island chains” This is a power projection perspective based on the PRC eventually gaining control of three imaginary chains of islands off of its East Coast. The first island chain, often referred to those included in the PRC’s “Nine Dash Line” mapping of the region, is bounded by Japan, Northwestern Philippines, Northern Borneo, Malaysia and Vietnam and includes all the waters within it. These are considered to be the PRC’s “inner sea” and its last line of maritime defense. This is a territory that the PRC is now claiming with its island-building projects in the South China Sea and increasingly assertive maritime presence in the East China Sea and the straits connecting them south of Taiwan.

The second island chain extends from Japan to west of Guam and north of New Guinea and Sulawesi in Indonesia, including all of the Philippines, Malaysian and Indonesian Borneo and the island of Palau. The third island chain, more aspirational than achievable at the moment, extends from the Aleutian Islands through Hawaii to New Zealand. It includes all of the Southwestern Pacific island states. It is this territory that is being geopolitically prepared by the PRC as a future sphere of influence, and which turns it into a contested zone.

(Source: Yoel Sano, Fitch Solutions)

The PRC approach to the Southwestern Pacific can be seen as a Two Level game. On one level the PRC is attempting to negotiate bilateral economic and security agreements with individual island States that include developmental aid and support, scholarship and cultural exchange programs, resource management and security assistance, including cyber security, police training and emergency security reinforcement in the event of unrest as well as “rest and re-supply” and ”show the flag” port visits by PLAN vessels. The Solomon Island has signed such a deal, and Foreign Minister Wang has made similar proposals to the Samoan and Tongan governments (the PRC already has this type of agreement in place with Fiji). The PRC has signed a number of specific agreements with Kiribati that lay the groundwork for a more comprehensive pact of this type in the future. With visits to Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and East Timor still to come, the approach has been replicated at every stop on Minister Wang’s itinerary. Each proposal is tailored to individual island State needs and idiosyncrasies, but the general blueprint is oriented towards tying development, trade and security into one comprehensive package.

None of this comes as a surprise. For over two decades the PRC has been using its soft power to cultivate friends and influence policy in Pacific Island states. Whether it is called checkbook or debt diplomacy (depending on whether developmental aid and assistance is gifted or purchased), the PRC has had considerable success in swaying island elite views on issues of foreign policy and international affairs. This has helped prepare the political and diplomatic terrain in Pacific Island capitals for the overtures that have been made most recently. That is the thrust of level one of this strategic game.

That opens the second level play. With a number of bilateral economic and security agreements serving as pillars or pilings, the PRC intends to propose a multinational regional agreement modeled on them. The first attempt at this failed a few days ago, when Pacific Island Forum leaders rejected it. They objected to a lack of detailed attention to specific concerns like climate change mitigation but did not exclude the possibility of a region-wide compact sometime in the future. That is exactly what the PRC wanted, because now that it has the feedback to its initial, purposefully vague offer, it can re-draft a regional pact tailored to the specific shared concerns that animate Pacific Island Forum discussions. Even if its rebuffed on second, third or fourth attempts, the PRC is clearly employing a “rinse, revise and repeat” approach to the second level aspect of the strategic game.

An analogy the captures the PRC approach is that of an off-shore oil rig. The bilateral agreements serve as the pilings or legs of the rig, and once a critical mass of these have been constructed, then an overarching regional platform can be erected on top of them, cementing the component parts into a comprehensive whole. In other words, a sphere of influence.

Western Reaction: Knee-Jerk or Nuanced?

The reaction amongst the traditional patrons has been expectedly negative. Washington and Canberra sent off high level emissaries to Honiara once the Solomon Islands-PRC deal was leaked before signature, in a futile attempt to derail it. The newly elected Australian Labor government has sent its foreign minister, sworn into office under urgency, twice to the Pacific in two weeks (Fiji, Tonga and Samoa) in the wake of Minister Wang’s visits. The US is considering a State visit for Fijian Prime Minister (and former dictator) Frank Baimimarama. The New Zealand government has warned that a PRC military presence in the region could be seriously destabilising and signed on to a joint US-NZ statement at the end of Prime Minister Ardern’s trade and diplomatic junket to the US re-emphasising (and deepening) the two countries’ security ties in the Pacific pursuant to the Wellington and Washington Agreements of a decade ago.

The problem with these approaches is two-fold, one general and one specific. If countries like New Zealand and its partners proclaim their respect for national sovereignty and independence, then why are they so perturbed when a country like the Solomon Islands signs agreements with non-traditional patrons like the PRC? Besides the US history of intervening in other countries militarily and otherwise, and some darker history along those lines involving Australian and New Zealand actions in the South Pacific, when does championing of sovereignty and independence in foreign affairs become more than lip service? Since the PRC has no history of imperialist adventurism in the South Pacific and worked hard to cultivate friends in the region with exceptional displays of material largesse, is it not a bit neo-colonial paternalistic of Australia, NZ and the US to warn Pacific Island states against engagement with it? Can Pacific Island states not find out themselves what is in store for them should they decide to play the Two Level Game?

More specifically, NZ, Australia and the US have different security perspectives regarding the South Pacific. The US has a traditional security focus that emphasises great power competition over spheres of influence, including the Western Pacific Rim. It has openly said that the PRC is a threat to the liberal, rules-based international order (again, the irony abounds) and a growing military threat to the region (or at least US military supremacy in it). As a US mini-me or Deputy Sheriff in the Southern Hemisphere, Australia shares the US’s traditional security perspective and emphasis when it comes to threat assessments, so its strategic outlook dove-tails nicely with its larger 5 Eyes partner.

New Zealand, however, has a non-traditional security perspective on the Pacific that emphasises the threats posed by climate change, environmental degradation, resource depletion, poor governance, criminal enterprise, poverty and involuntary migration. As a small island state, NZ sees itself in a solidarity position with and as a champion of its Pacific Island neighbours when it comes to representing their views in international fora. Yet it is now being pulled by its Anglophone partners into a more traditional security perspective when it comes to the PRC in the Pacific, something that in turn will likely impact on its relations with the Pacific Island community, to say nothing of its delicate relationship with the PRC.

In any event, the Southwestern Pacific is a microcosmic reflection of an international system in transition. The issue is whether the inevitable conflicts that arise as rising and falling Great Powers jockey for position and regional spheres of influence will be resolved via coercive or peaceful means, and how one or the other means of resolution will impact on their allies, partners and strategic objects of attention such as the Pacific Island community.

In the words of the late Donald Rumsfeld, those are the unknown unknowns.

Media Link: “A View from Afar” podcast returns.

After a brief hiatus, the “A View from Afar” podcast is back on air with Selwyn Manning leading the Q&A with me. This week is a grab bag of topics: Russian V-Day celebrations, Asian and European elections, and the impact of the PRC-Solomon Islands on the regional strategic balance. Plus a bunch more. Check it out.

Media Link: AVFA on small state approaches to multilateral conflict resolution in transitional times.

In this week’s “A View from Afar” podcast Selwyn Manning and I used NZ’s contribution of money to purchase weapons for Ukraine as a stepping stone into a discussion of small sate roles in coalition-building, multilateral approaches to conflict resolution and who and who is not aiding the effort to stem the Russian invasion. We then switch to a discussion of the recently announced PRC-Solomon Islands security agreement and the opposition to it from Australia, NZ and the US. As we note, when it comes to respect for sovereignty and national independence in foreign policy, in the cases of Ukraine and the Solomons, what is good for the goose is good for the gander.

We got side-tracked a bit with a disagreement between us about the logic of nuclear deterrence as it might or might not apply to the Ruso-Ukrainian conflict, something that was mirrored in the real time on-line discussion. That was good because it expanded the scope of the storyline for the day, but it also made for a longer episode. Feel free to give your opinions about it.

Redrawing the lines.

Early this year I was asked by a media outlet to appear and offer predictions on what will happen in world affairs in 2022. That was a nice gesture but I wound up not doing the show. However, as readers may remember from previous commentary about the time and effort put into (most often unpaid) media preparation, I engaged in some focused reading on international relations and comparative foreign policy before I decided to pull the plug on the interview. Rather than let that research go to waste I figured that I would briefly outline my thoughts about that may happen this year. They are not so much predictions as they are informal futures forecasting over the near term horizon.

The year is going to see an intensification of the competition over the nature of the framework governing International relations. If not dead, the liberal institutional order that dominated global affairs for the better part of the post-Cold War period is under severe stress. New and resurgent great powers like the PRC and Russia are asserting their anti-liberal preferences and authoritarian middle powers such as Turkey, North Korea, Saudi Arabia and Iran are defying long-held conventions and norms in order to assert their interests on the regional and world stages. The liberal democratic world, in whose image the liberal international order was ostensibly made, is in decline and disarray. In this the US leads by example, polarized and fractured at home and a weakened, retreating, shrinking presence on the world stage. It is not alone, as European democracies all have versions of this malaise, but it is a shining example of what happens when a superpower over-extends itself abroad while treating domestic politics as a centrifugal zero sum game.

While democracies have weakened from within, modern authoritarians have adapted to the advanced telecommunications and social media age and modified their style of rule (such as holding legitimating elections that are neither fair or free and re-writing constitutions that perpetuate their political control) while keeping the repressive essence of it. They challenge or manipulate the rule of law and muscle their way into consolidating power and influence at home and abroad. In a number of countries democratically elected leaders have turned increasingly authoritarian. Viktor Orban In Hungary, Recep Erdogan in Turkey, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, and Narendra Modi in India (whose Hindutva vision of India as an ethno-State poses serious risks for ethnic and religious minorities), all evidence the pathology of authoritarianism “from within.”

Abroad, authoritarians are on the move. China continues its aggressive maritime expansion in the East and South China Seas and into the Pacific while pushing its land borders outwards, including annexing territory in the Kingdom of Bhutan and clashing with Indian troops for territorial control on the Indian side of their Himalayan border. Along with military interventions in Syria, Libya and recently Kazakstan, Russia has annexed parts of Georgia and the Donbas region in eastern Ukraine, taken control of Crimea, and is now massing troops on the Ukrainian border while it demands concessions from NATO with regard to what the Russians consider to be unacceptable military activity in the post-Soviet buffer zone on its Western flank. The short term objective of the latest move is to promote fractures within NATO over its collective response, including the separation of US security interests from those of its continental partners. The long term intention is to “Findlandize” countries like Ukraine, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania so that they remain neutral, or at least neutralized, in the event of major conflict between Russia and Western Europe. As Churchill is quoted as saying, but now applied to Vladimir Putin, “he may not want war. He just wants the fruits of war.”

>>Aside about Russia’s threat to the Ukraine: The Russians are now in full threat mode but not in immediate invasion mode. To do that they need to position water and fuel tankers up front among the armoured columns that will be needed to overcome Ukrainian defences, and the 150,000 Russian troops massed on the eastern Ukrainian border are not sufficient to occupy the entire country for any length of time given Ukrainian resistance capabilities, including fighting a protracted guerrilla war on home soil (at least outside Russian ethnic dominant areas in eastern Ukraine). The Russians know that they are being watched, and satellite imagery shows no forward positioning of the logistical assets needs to seize and hold Ukrainian territory for any length of time. Paratroops and light infantry cannot do that, and while the Russians can rapidly deploy support for the heavier forces that can seize and hold hostile territory, this Russian threat appears to be directed, at best, at a limited incursion into Russian-friendly (read ethnic) parts of eastern Ukraine. That gives the Ukrainians and their international supporters room for negotiation and military response, both of which may be essential to deter Russian ambitions vis a vis the fundamental structure and logic of European security.<<

Rather than detail all the ways in which authoritarians are ascendent and democrats descendent in world affairs, let us look at the systemic dynamics at play. What is occurring is a shift in the global balance of power. That balance is more than the rise and decline of great powers and the constellations aggregated around them. It is more than about uni-, bi-, and multipolarity. It refers to the institutional frameworks, norms, practices and laws that govern the contest of States and other international actors. That arrangement—the liberal international order–is what is now under siege. The redrawing of lines now underway is not one of maps but of mores.

The liberal international order was essentially a post-colonial creation made by and for Western imperialist states after the war- and Depression-marked interregnum of the early 20th century. It did not take full hold until the collapse of the Soviet Union, as Cold War logics led to a tight bipolar international system in which the supposed advantages of free trade and liberal democracy were subordinated to the military deterrence imperatives of the times. This led to misadventures and aberrations like the domino theory and support for rightwing dictators on the part of Western Powers and the crushing of domestic political uprisings by the Soviets in Eastern Europe, none of which were remotely “liberal” in origin or intent.

After the Cold War liberal internationalists rose to positions of prominence in many national capitals and international organizations. Bound together by elite schooling and shared perspectives gained thereof, these foreign policy-makers saw in the combination of democracy and markets the best possible political-economic combine. They consequently framed much of their decision-making around promoting the twin pillars of liberal internationalism in the form of political democratization at the national level and trade opening on a global scale via the erection of a latticework of bi- and multilateral “free” trade agreements (complete with reductions in tariffs and taxes on goods and services but mostly focused on investor guarantee clauses) around the world.

The belief in liberal internationalism was such that it was widely assumed that inviting the PRC, Russia and other authoritarian regimes into the community of nations via trade linkages would lead to their eventual democratization once domestic polities began to experience the material advantages of free market capitalism on their soil. This was the same erroneous assumption made by Western modernization theorists in the 1950s, who saw the rising middle classes as “carriers” of democratic values even in countries with no historical or cultural experience with that political regime type or the egalitarian principles underbidding it. Apparently unwilling to read the literature on why modernization theory did not work in practice, in the 1990s neo-modernization theorists re-invented the wheel under the guise of the Washington Consensus and other such pro-market institutional arrangements regulating international commerce.

Like the military-bureaucratic authoritarians of the 1960s and 1970s who embraced and benefited from the application of modernization theory to their local circumstances (including sub-sets such as the Chicago School of macroeconomics that posited that finance capital should be the leader of national investment decisions in an economic environment being restructured via the privatization of public assets), in the 1990s the PRC and Russia welcomed Western investment and expansion of trade without engaging in the parallel path of liberalizing, then democratizing their internal politics. In fact, the opposite has occurred: as both countries became more capitalistic they became increasingly authoritarian even if they differ in their specifics (Russia is a oligopolistic kleptocracy whereas the PRC is a one party authoritarian, state capitalist system). Similarly, Turkey has enjoyed the fruits of capitalism while dismantling the post-Kemalist legacy of democratic secularism, and the Sunni Arab petroleum oligarchies have modernized out of pre-capitalist fossil fuel extraction enclaves into diversified service hubs without significantly liberalizing their forms of rule. A number of countries such as Brazil, South Africa and the Philippines have backslid at a political level when compared to the 1990s while deepening their ties to international capital. Likewise, after a period of optimism bracketed by events like the the move to majority rule in South Africa and the “Arab Spring,” both Saharan and Sub-Saharan Africa have in large measure reverted to the rule of strongmen and despots.

As it turns out, as the critics of modernisation theory noted long ago, capitalism has no elective affinity for democracy as a political form (based on historical experience one might argue to the contrary) and democracy is no guarantee that capitalism will moderate its profit orientation in the interest of the common good.

Countries like the PRC, Russia, Turkey and the Arab oligarchies engage in the suppression and even murder of dissidents at home and abroad, flouting international conventions when doing so. But that is a consequence, not a cause of the erosion of the liberal international order. The problem lies in that whatever the lip service paid to it, from a post-colonial perspective liberal internationalism was an elite concept with little trickle down practical effect. With global income inequalities increasing within and between States and the many flaws of the contemporary international trade regime exposed by the structural dislocations caused by Covid, the (neo-)Ricardian notions of comparative and competitive advantage have declined in popularity, replaced by more protectionist or self-sufficient economic doctrines.

Couple this with disenchantment with democracy as an equitable deliverer of social opportunity, justice and freedom in both advanced and newer democratic states, and what has emerged throughout the liberal democratic world is variants of national-populism that stress economic nationalism, ethnocentric homogeneity and traditional cultural values as the main organizing principles of society. The Trumpian slogan “America First” encapsulates the perspective well, but support for Brexit in the UK and the rising popularity of rightwing nationalist parties throughout Europe, some parts of Latin America and even Japan and South Korea indicates that all is not well in the liberal world (Australia and New Zealand remain as exceptions to the general rule).

That is where the redrawing comes in. Led by Russia and the PRC, an authoritarian coalition is slowly coalescing around the belief that the liberal international order is a post-colonial relic that was never intended to benefit the developing world but instead to lock in place an international institutional edifice that benefitted the former colonial/imperialist powers at the expense of the people that they directly subjugated up until 30-40 years ago. What the PRC and Russia propose is a redrawing of the framework in which international relations and foreign affairs is conducted, leading to one that is more bound by realist principles rooted in power and interest rather than hypocritically idealist notions about the perfectibility of humankind. It is the raw understanding of the anarchic nature of the international system that gives the alternative perspective credence in the eyes of the global South.

Phrased differently, there is truth to the claims that the liberal international order was a post-colonial invention that disproportionally benefitted Western powers. Because the PRC and USSR were major supporters of national liberation and revolutionary movements throughout the so-called “Third World” ranging from the Middle East, Sub-Saharan Africa, Central and SE Asia to Central and South America, they have the anti-Western credentials to promote a plausible alternative cloaked not in the mantle of purported multilateral ideals but grounded in self-interested transactions mediated by power relationships. China’s Belt and Road initiative is one example in the economic sphere, and Russian military support for authoritarians in Syria, Iran, Cuba and Venezuela shows that even in times of change it remains steadfast in its pragmatic commitment to its international partners.

With this in mind I believe that 2022 will be a year where the transition from the liberal international order to something else will begin to pick up speed and as a result lead to various types of conflict between the old and new guards. What with hybrid or grey area conflict, disinformation campaigns, electoral meddling and cyberwarfare all now part of the psychological operations mix along with conventional air, land, sea and space-based kinetic military operations involving multi-domain command, control, communications, computing, intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance and robotics (C4ISR2) systems, the ways in which conflict can be engaged covertly or overtly have multiplied. That technological fact means that it is easier for international actors, or at least some of them, to act as disruptors of the global status quo by using conflict as a systemic re-alignment vehicle.

Absent a hegemonic power or Leviathan, a power vacuum has opened in which the world is open to the machinations of (dare I say it?) “charismatic men of destiny.” Putin, Xi Jingpin and other authoritarians see themselves as such men. Conflict will be the tool with which they attempt to impose their will on international society.

For them, the time is now. With the US divided, weakened and isolated after the Trump presidency and unable to recover quickly because of Covid, supply chain blockages, partisan gridlock and military exhaustion, with Europe also rendered by unprecedented divisions and most of the rest of the world adopting“wait and see” or hedging strategies, the strategic moment is opportune for Russia, China and lesser authoritarian powers to make decisive moves to alter the international status quo and present the liberal democratic world with a fait accompli that is more amenable to their geopolitical interests.

If what I propose is correct, the emerging world system dominated by authoritarian States led by the PRC and Russia will be less regulated (in the sense that power politics will replace norms, rules and laws as the basic framework governing inter-state relations), more fragmented (in that the thrust of foreign policies will be come more bilateral or unilateral rather than multilateral in nature), more coercive and dissuasive in its diplomatic exchanges and increasingly driven by basic calculations about power asymmetries (think “might makes right” and “possession is two thirds of the law”). International organisations and multilateral institutions will continue to exist as covers for State collusion on specific issues or as lip service purveyors of diplomatic platitudes, but in practice will be increasingly neutralised as deliberative, arbitrating-mediating and/or conflict-resolution bodies. Even if not a full descent into international anarchy, there will be a return to a Hobbesian state of nature.

2022 could well be the year that this begins to happen.

Update: For an audio short take on what 20022 may bring, please feel free to listen to the first episode of season three of “A View from Afar,” a podcast that offers a South Pacific perspective on geopolitical and strategic affairs co-hosted by Selwyn Manning and me.

A democratic peace or a feminist peace?

Many years ago when I was in mid academic career, two theoretical strands emerged in the field of international relations and comparative foreign policy. One was the basis for a school of thought that came to be known as feminist international relations theory, which to crudely oversimplify one sub-strand, posited that women have different and less conflictual approaches to politics and therefore, among other things, a world that had more female leaders would likely be a more peaceful one. The second came out of the the democratization literature and, again crudely oversimplified, posited that democracies were less prone to engage in war and therefore a world with more democracies would be a more peaceful one. Although neither strand specifically addressed the possibility, one can infer that if these notions are true a world of women-led democracies would be a Garden of Eden when compared to its present state.

The two strands have existed in parallel since the early 1990s and continue to be much debated, refined, debunked, reformulated and extended. Arguments over the merits of each continue to this day even though I personally have not contributed to them like I once did (and to be honest I only contributed in an insignificant way to what is known as the democratic peace thesis debate and not the feminist IR debate, which is a minefield for male scholars).

Recently a good friend whose views I hold in high regard sent me an article titled ” The Gender Gap Is Taking Us to Unexpected Places” by Thomas B. Edsall of the New York Times (January 12, 2022). Mr. Edsall is an astute reader of politics and his column is well worth following. His article covers a lot of ground and is worth reading in its entirety but what struck me was this discussion of women’s impact on politics. I have quoted the relevant passage.

“Take the argument made in the 2018 paper “The Suffragist Peace” by Joslyn N. Barnhart of the University of California-Santa Barbara, Allan Dafoe at the Center for the Governance of AI, Elizabeth N. Saunders of Georgetown and Robert F. Trager of U.C.L.A.:

Preferences for conflict and cooperation are systematically different for men and women. At each stage of the escalatory ladder, women prefer more peaceful options. They are less apt to approve of the use of force and the striking of hard bargains internationally, and more apt to approve of substantial concessions to preserve peace. They impose higher audience costs because they are more approving of leaders who simply remain out of conflicts, but they are also more willing to see their leaders back down than engage in wars.

The increasing incorporation of women into “political decision-making over the last century,” Barnhart and her co-authors write, raises “the question of whether these changes have had effects on the conflict behavior of nations.”

Their answer: “We find that the evidence is consistent with the view that the increasing enfranchisement of women, not merely the rise of democracy itself, is the cause of the democratic peace.” Put another way, “the divergent preferences of the sexes translate into a pacifying effect when women’s influence on national politics grows” and “suffrage plays a direct and important role in generating more peaceful interstate relations by altering the political calculus of democratic leaders.”

That is a pretty strong claim with important implications for the recruitment of women into political management roles. My friend and I corresponded about the article and I thought that it would provide some food for thought for KP readers if I copied and reprinted some of my commentary to her. It is by no means a scholarly treatise or deeply grounded in the literatures pertinent to the subject, but it addresses the issue of whether women’s participation in politics leads to more peaceful/less conflictual political outcomes. Here is what I had to say (in quotes).

“Interesting thesis (that the enfranchisement of women, not democracy per se, contributes to the democratic peace thesis). Of course there has long been a view that if we only had more women in politics there would be less conflict. Tell that to Maggie Thatcher!

In the late 1980s I supervised student research that analyzed the impact of women in revolutionary movements on post-revolutionary social policy agendas. The cases studied were Cuba, Nicaragua, Colombia and El Salvador (two successful revolutions, two peace process-incorporated revolutionary movements so as to allow for proper comparative analysis using a most-similar/most different paired case study design). The results found that the more women participated in combat roles during the revolutionary wars, the more likely that they would be included in post-revolutionary policy decision-making, especially in traditionally female policy areas like family planning, health, education etc. Abortion rights were tied to that as well.

In places where women served as camp followers, concubines, cooks and in other non-combat roles tied to the revolutionary armies, they were excluded from post-revolutionary social policy making, even in traditionally female policy areas. The conclusion my student drew was that men respected women who fought alongside them and took the risks inherent in doing so. In my own experience and study, I have also found that under fire women were/are no more or less cowardly than men, by and large, especially when they received the same guerrilla training, so I accept this view. My student’s research also showed that the reverse was true: men did not respect as equals women who fulfilled “traditional” non-combat roles.

This translated into very different attitudes towards incorporating women into the leadership cadres once the revolution was over (be they as part of a victorious coalition or when incorporated into post-settlement political parties and governments). That was especially the case for women who showed combat leadership skills under fire, in many cases due to the fact that so many male field-level guerrilla leaders were killed that women were forced step into the breach (sometimes from non-combat roles) in order to sustain the fight.

So basically, if women behaved “like men” in combat, they were accorded respect and inclusion in post-revolutionary policy making, at least in traditionally female policy areas. Or as I used to joke, can you imagine the reaction of these Sandinista sisters coming home from a hard day arguing with their male revolutionary leaders about neonatal and early childhood health care, abortion rights and domestic violence mitigation, only to have their oaf male partners shout out from the sofa that she/they should get him another cerveza? Let’s just say that there would be no “yes, dear” in their responses.

That was an interesting but incomplete conclusion. I am among other things a student of the path-dependency institutionalist school of comparative politics. That is, current institutions are the product of previous choices about those institutions, which in turn set the boundaries for future choices about those institutions. Once a choice is made about the purpose and shape of an agency or institution, it leads down a path of subsequent “bounded” choices–that is, choices made within the framework or confines established by the original choice. I often use Frost’s poem “The Road Not Taken” or the phrase “a path less chosen” to illustrate the concept. You come to a fork on the trail, and your (hiking) destiny is determined by which route you take. There might be a hungry grizzly on one, and a pristine mountain lake bordering on a serene meadow on the other, but you do not know that at the time you make your decision OR, you know what is ahead and steer accordingly with purposeful intent.

Political institutions are by and large created by and for men. They are masculine in that sense–they arise from the minds of men about how politics should be codified and operationalised. The original choices on institutional configuration and mores were made by and for men, as have most of what followed regardless of regime type. The comment in Edsell’s article about academia being a male domain (up until recently) that channels male competitive urges about status etc. into scholarship is true for political institutions as well (and business, needless to say). Now here is where things get tricky.

For women to do well in these male domains, they must initially “outboy the boys.” Early feminists confronted this in spades, and when they did play hard just like the boys, they were called dykes and worse regardless of their true sexuality. But the problem is deeper than misogynist weirdness and reactions. As the study of revolutionary women showed, they had to adopt male roles and behave as if or just like they were men in order to advance in the organization and achieve ultimate policy goals that were female in orientation. They had to play along in order to not only get along but to move the policy needle in a “feminine” or female-focused direction. But that meant being less feminine in order to prosper. No softness, no weakness (emotional or physical), no “girly” concerns (say, like lipstick or nice clothes) were permissible because that relegated them, IN THE EYES OF MEN, as too fragile and irrational to be respected as peers.

Extending the concept from revolutionary movements to democracies, what that means is that women entering into politics have to conform to the masculine attributes of the institutions that they have entered. Sure, they can change cosmetic things like male-only cigar lounges or dining rooms, but the entire vibe/aura/mana of these institutions is male-centric in everything that they do. Add to that institutional inertia–that is, the tendency of institutions to favor carrying forward past practices and mores (often in the name of “tradition” or “custom and usage”)–and what we get is women who are politically socialized by the institutions that they join to behave in masculine ways, at least when within the institution and carrying out the roles assigned to them by the institution. That makes changing the institution more important than changing the people within it, but that is also why institutions are loath to change (think of resistance to changing the US from a presidential two-party system to a parliamentary MMP-style system). Perhaps the NZ Green Party are onto something with their gender-balanced party caucus selections, but they remain inserted in a larger parliamentary “nested game” with origins and continuities grounded in masculinist behaviour and perceptions.

More broadly, just like we are a product of our upbringings moderated by the passage of time and experience, so too women in politics are institutionally socialized to respond and behave in certain ways. And those ways are masculine, not feminine. If the bounded rationalities of the institutional nested games in which women “play” are male-centric/dominant, then it is unsurprising that women who succeed in them do so because they adopt those rationalities as their own (even if their better angels incline them to more “feminine” approaches to institutional problem-solving). That includes the propensity for conflict and war.

Of course this is not a hard and fast universal rule. Jacinda Ardern is not Helen Clark. But then think of Hillary Clinton as well as Margaret Thatcher. Or Michelle Bachelet. Or Helen Clark if NZ was deliberately attacked in some fashion. I do not think that she would opt for compromise and concession rather than conflict, and I sure as heck do not think that Hillary would turn the other cheek when it comes to Putin invading the Ukraine. But what turned these young idealists into the battle axes they are now? I would suggest that it is their political socialization within masculine institutions.

So, as I mentioned, the franchise of women=less conflict thesis is intriguing but needs more work. Male and female traits and values may be the independent variables and propensity towards or against conflict may be the dependent variable, but the intervening variable is institutions, and more specifically, the bounded rationalities of the nested games that they impose on men and women because of the path-dependent nature of their histories as human agencies. Once we get that figured out and change the masculine nature of pretty much 90 percent of human institutions, then perhaps we will have a chance at a more peaceful world. But with lots of snark.”

Reader’s views are welcome.

Indigenous socialism with a Chilean face.

Happy New Year everyone.

I am, by personal and professional inclination, loathe to speculate on uncertain future events. On the other hand, I have an abiding interest in distant political processes even though I cannot claim particular analytic expertise when considering them. Thus, when watching the recent Chilean presidential election from afar, I found myself wanting to offer a view while being unable to realistically give a prediction or even outline what the future course of affairs will be beyond the inauguration of Chile’s new president in March. An exchange with a long term reader (Edward Main) during the holiday break led me to look closer into the matter. With that in mind, I hope that readers will take the following as an interested bystander’s observations rather than an expert reflection of the ongoing turn of events.

Five days before Christmas and 51 years after Salvador Allende was elected as the first socialist president in Chilean history, Gabriel Boric re-made history as the youngest candidate (35) to win that office. A former student activist and Congressman from Punta Arenas in Tierra del Fuego, he first rose to prominence during the 2011 student demonstrations against increases in tuition fees at the University of Chile, then again during the 2019 anti-austerity demonstrations precipitated by a 30 percent rise in public transportation prices in Santiago. In 2021 Boric rode a wave of votes (the most since mandatory voting laws were dropped in 2012) to win 56 percent of the national ballot (although less than 60 percent of eligible voters cast ballots, leaving a large pool of disaffected or apathetic voters in the political mix). He campaigned on an overtly socialist, specifically anti-neoliberal agenda, promising to tax the super rich, expand social services and environmental conservation programs, promote pension reform and universal health care and make the fight against income inequality his main priority in a country with the worst income gaps in South America.

Boric’s victory is remarkable given the tone of the campaign. His opponent, Jose Antonio Kast, embraced Trumpian-style rhetoric and openly said that he would be the “Bolsonaro of Chile” (Jair Bolsonaro is the national-populist president of Brazil who emulates Trump, now hospitalized because of complications from a knife attack in 2018). He railed against Boric as someone who would turn Chile into Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, or even Peronist Argentina. Kast is the son of a card-carrying Nazi who fled to Chile after WW2 and built a sausage-making business that served as a launching pad for his children’s economic and political ambitions during the Pinochet dictatorship (the Kast family dynasty is prominent in Chilean rightwing circles). Jose Antonio Kast openly praised the strongman and his neoliberal economic policies during his presidential campaign while downplaying the thousands of murdered, tortured and exiled victims of Pinochet’s regime. He won a plurality of votes in the presidential primaries but lost decisively in the second round run-off between the two largest vote-getters.

Surprisingly given their vitriol during the campaign, both Kast and the outgoing president, rightwing Sebastian Pinera (son of a Pinochet Labour Minister who happened to be a friend of my father) extended their congratulations and offers of support to the newly elected Boric, who will be inaugurated in March. This makes the transition period especially important, as it may offer a window of opportunity for Boric to negotiate inter-partisan consensus on key policy issues.

Boric’s election follows that of several other Leftist presidential candidates in Latin America in the last two years, including those in Bolivia (a successor to the illegally ousted Evo Morales), Peru (an indigenous school teacher and teacher’s union leader) and Honduras (the wife of a former president ousted by a coup tacitly backed by the Obama administration). Centre-Left presidents govern in Belize, Costa Rica, Guyana, Mexico, Panama, and Suriname. A former leftwing mayor of Bogota is the front runner in this year’s Colombian presidential elections (now in Right-center hands) and former president Lula da Silva is leading the polls against Bolsonaro for the October canvass in Brazil. These freely elected Leftists are bookended on one end by authoritarian counterparts in Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela and on the other by right-leaning elected governments in Brazil, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala Paraguay and Uruguay. Argentina, which has a Peronist government, straddles the divide between Left and Right owing to the odd (and very kleptocratic) populist coalition that makes up the governing Party.

One might say that the region is relatively balanced ideologically speaking, but with an emerging tilt to the moderate Left as a result of the exposure by the pandemic of inherent flaws in the market driven economic model that dominated the region over the last thirty years. It remains to be seen if this political tilt will eventuate in the type of socio-economic reforms upon which the successful Leftists candidates campaigned on. What is pretty clear is that it will not be a repeat of the so-called “Pink Tide” that swept the likes of Hugo Chavez and Evo Morales into power in the early 2000s, both in terms of the extent of their policy ambitions and the style in which they rule. This most recent wave still retains many characteristics of the much lauded (by the Left) indigenous socialism of twenty years ago, but it is now tempered by the policy failures and electoral defeats that followed its heyday. It is indigenous not only because of its origins in populations that descended from pre-colonial civilizations (although there is still plenty of indigena in Latin American socialism), but because it originates in domestic and regional ideological thought and practice. Within this dual sense of the phrase, it is moderation and pragmatism that appears to differentiate the original 2000s versions from what is emerging today.

Western observers believe that the regional move Left may give China an opportunity to make strategic inroads in the hemisphere. That view betrays ignorance of the Latin American Left, which is not driven by any Communist orthodoxy or geopolitical alignment with China (or even blind hatred of the US), but instead is a very heterogenous mix of indigenous, environmental, trade union, student and social movement activism that among other things is progressive on gender and sexuality rights and climate change. This is not a Leninist/Maoist Left operating on vanguardist principles of “democratic centralism,” but instead a fluid amalgam of modern (industrial) and post-modern (post-industrial) causes. What that means is, since China is soon to overtake the US as the primary extractor of raw materials and primary goods from Latin America and has a checkered environmental record as part of its presence as well as a record of authoritarian management practices in Chinese controlled firms, it is by no means certain that it will be able to leverage emergent elected Latin American Left governments in its favor.

In fact, given what has been seen in its relationship with the three authoritarian leftist states, many of the elected Leftist governments may prove reticent to deepen ties with the Asia giant precisely because of concerns about a loss of economic independence (fearing debt diplomacy, among other things). The Belt and Road initiative may seem an attractive proposition at first glance, but it can also serve to choke national sovereignty on the economic as well as diplomatic fronts. Boric and his supporters are very much aware of this given problems that have risen from Chinese investment in the Chilean mining and forestry sectors (such as disputes over water and indigenous land rights).

This is worth mention as a relevant aside. Chile’s economy remains primary good export oriented. The bulk of its GDP is derived from mining, forestry, fishing and agriculture, including value added products such as wine. Recently, lithium deposit exploitation has exploded across the so-called “lithium triangle” comprised of northwest Argentina, southwestern Bolivia and northeaster Chile, with Chinese investors jockeying for position with Western interests in the development of salt flat mining in which lithium is extracted for commercial purposes in an increasingly e-based global economy. Such mining is environmentally damaging and machine intensive, so the benefits accrued go to those who can afford to invest in it rather than to workers associated with it. Chinese firms compete on the bottom line, not on social responsibility.

The political economic consequences of this dependence on primary good exports fuelled by foreign investment follows a larger pattern whereby Chilean economic elites resist public investment in anything other than service industries connected to primary good supply chains and ancillary businesses (input and output logistics, highways, port infrastructure and the legal and commercial apparatuses attendant to them). This has made for a significant urban-rural divide when it comes to economic opportunity, something that is not alleviated by the proliferation of universities and private education institutions during the last 30 years. In fact, the Chilean economic model discourages investment in value-added technological innovation that would undermine the primacy of the primary good export sector as the dominant economic, social and political constellation. Instead, Right governments have used low export tax policy as a means of promoting “trickle down” opportunity to those inserted into the main productive sectors while Left leaning governments have used tax revenues on exports as a means of alleviating social inequalities and dysfunction while expanding the service sector middle class. As the 2019 demonstrations made clear, neither has worked. Boric’s presidency has that as its fundamental conundrum.

That brings up the internal political dynamics at play in Chile. For Boric to succeed he will have to deliver on very high public expectations. For that to happen he needs to navigate a three-cornered political obstacle course.

In one corner is his own political support base, which is comprised of numerous factions with different priorities, albeit all on the “Left” side of the policy agenda. This include members of the Constitutional Convention charged with drawing up a replacement for the Pinochet-era constitution still in force (something that was agreed to by the outgoing government in the wake of the 2019 protests). The Convention must design a new constitution with procedural as well as substantive features. That is, it must demarcate governance processes as well as grant enshrined rights. The balance between the two is tricky, because a minimalist approach that focuses on processes and procedures (such as elections, office terms and separation of powers) does not address what constitutes a “right” in a democracy and who should have rights bestowed upon them, whereas an encompassing approach that attempts to cover the universe of social endeavour risks granting so many rights to so many people and agencies that it overwhelms regulatory processes and becomes meaningless is real terms (the latter happened with the 1988 Brazilian constitutional reform, which covers a plethora of topics that have been cumbersome to enforce or implement in practice).

Not all of the delegates share the gradualist, incremental, moderately pragmatic approach to policy agenda-setting that Boric espouses, and because they are independently elected, it signals that the future of Chile resides in a very much redesigned approach to governance. It is even possible that delegates consider moving from a presidential to a parliamentary democracy given that Chile already has a very splintered party system that requires the building multiparty coalitions to form majorities in any event. Whatever is put on the table, Boric will have to urge delegates to exercise caution when it comes to sensitive issues like taxation, military funding and autonomy, land reform (including indigenous land rights, which have been the source of violent clashes in recent years) etc., less it provoke a destabilizing backlash from conservative sectors. In light of that and the strength of his election victory, it will be interesting to see how Boric approaches the Constitutional Convention, how his Cabinet shapes up in terms of personnel and policy orientation, and how his support bloc in Congress responds to his early initiatives.

The latter matters because Boric inherits a deeply fragmented Congress that has a slim Opposition majority but which in fact has seen all centrist parties lose ground to more extreme parties on both the Right and Left. Even so and depending on the issue, cross-cutting alliances within Congress currently transcend the usual Left-Right divide, so it is possible that he will be able to use his incrementalist moderate approach to advance a Left-nationalist project that keeps most parties aligned or at least does not step on too many Party toes. On the other hand, the fact Boric won 56 percent of a vote in which only 56 percent of eligible voters went to the polls means that his policy proposals could easily be rejected on partisan grounds given the lack of unified majorities on either side of the ideological divide.

In another corner are the political Opposition, dominated by Pinochetista legacies but increasingly interspersed with neo-MAGA and alt-Right perspectives (what I shall call Chilean nationalist conservatism). The Right has a significant presence in the Constitutional Convention so may be able to act as a brake on radical reforms and in doing so create space for Boric and his supporters in the convention to push more moderate alterations to the magna carta (each constitutional change requires a 2/3 vote in order to pass. This will force compromise and moderation by the drafters if anything is to be achieved).

The fact that Pinera and Kast, scions of the Pinochetista wing (they do not like that name and disavow ties to the dictatorship other than support for its “Chicago School” economic policies), readily conceded and offered support to Boric may indicate that the neoliberal wing of Chilean conservatism understands that many rightwing voters may have abstained from voting or voted for Boric on economic nationalist grounds as a result of Pinera’s adherence to market-oriented policies that clearly were not alleviating poverty or providing effective pandemic relief even as the upper ten percent of society continued to capture an increasing percentage of national wealth. This could mean that the Chilean Right is less disloyal to the democratic process as it was in the run up to Allende’s election and therefore more committed—or at least some of it is—to trying to reach compromises with Boric on pressing policy issues. In that sense their presence in the Constitutional Convention may prove to be a moderating influence.

Conversely, in the wake of the defeat the Chilean Right might fragment between Pinochetista and newer factions, which will mean that conciliation with government initiatives will be difficult until the internal power struggle within the Right is resolved, and then only if it is resolved in a way that marginalizes Trump and Bolsonaro-inspired extremists within conservative ranks. After all, what sells in the US or Brazil does not necessarily sell in Chile. The most important arena in which this internal dispute will have to be resolved is Congress, where extreme Right parties have taken seats from traditional conservative vehicles. On the face of it that spells trouble for Boric, but the narrow Right majority in Congress and Pinochetista disdain for their extreme counterparts may grant him some room for manoeuvre.

In a very real sense, Boric’s political fate will be determined in the first instance by the coalition politics within his own support base as well as within the Right Opposition.

The final obstacle is getting the Chilean military on-board with the new government’s project. Of the three factors in this political triumvirate, the armed forces are both a constant and a wild card. They are a constant in that their deeply conservative disposition and institutional legacies are unshakable and guaranteed. This means that Boric’s government must tread delicately when it comes to civil-military affairs, both in terms of national security policy-making but also with regard to the prerogatives awarded the armed forces under the Pinochet constitution. Along with the Catholic Church and landed agricultural interests, the Chilean armed forces are one of the three pillars of traditional Chilean conservatism. This ideological outlook extends to the national paramilitary police, the Carabineros, who are charged with domestic security and repression (the two overlap but are not the same).

Democratic reforms (such as allowing female combat pilots) have been introduced into the military, especially during the tenure of former president Michelle Bachelet as Defense Minister, but the overall tone of civil-military relations over the years since democracy was restored (1990) has been aloof, when not tense. Revelations that Pinochet and other senior offices had received kickbacks from weapons dealers produced a paratrooper mutiny in 1993, and when Pinochet returned from voluntary exile in the UK in 2000 he was greeted with full military honors in a nationally televised airport ceremony. This rekindled old animosities between Right and Left that saw the military high command issue veiled warnings about leaving sleeping dogs lie. Until now, that warning has been heeded.

The role of the military as political guarantor and veto agent is enshrined in the Pinochet constitution. So is its receipt of a percentage of pre-tax copper exports. These powers and privileges have been pared down but not eliminated entirely over the years and will be a major focus of attention of the Constitutional Convention. With 7,800 kilometers of land bordering on three states that it has had wars with and 6,435 kilometers of ocean frontage extending out to Easter Island (and all the waters within that strategic triangle), the Chilean military is Army-dominant even if the other two service branches are robust given GDP and population size (in fact, the Chilean military is one of the most modernized in Latin America thanks to its direct access to copper revenues). What this means is that the Chilean armed forces exhibit a state of readiness and geopolitical mindset that is distinct from that of most of its neighbors and which gives it unusual domestic political influence.

The Chilean armed forces High Command continues to operate according to Prussian-style organizational principles that, if instilling professionalism and discipline within the ranks, also leads to highly concentrated and centralized decision-making authority in the services Flag-rank leadership. Moreover, although the Prussian legacy has diluted in recent years (with the Army retaining significant Prussian vestiges, to include parade march goose-stepping, while the Air Force and Navy have adored UK and US organizational models), the Chilean Navy is widely seen as a bastion for the most conservative elements in uniform, with the Air Force encompassing the more “liberal” wing of the officer corps and the Army and Carabineros leaning towards the Navy’s ideological position. The effect is to make democratic civil-military relations largely hinge on the geopolitical perspectives and attitudes of service branch leaders towards the elected government of the day.

Successfully navigating these three obstacle points will be the key to Boric’s success. The groundwork for that is being laid now, in the period between his election and inauguration. Should he be able to reach agreement with supporters and opposition on matters like the scope of constitutional reform and short-term versus medium-term fiscal and other policy priorities in the midst of a public health crisis, then his chances of leaving a legacy of positive change are high. Should he not be able to do so, then his attempt to impart a dose of pragmatism and moderation on Chilean indigenous socialism could well end in disarray.

We can only hope that for Boric and for Chile, the country advances por la razon y no por la fuerza.

The incremental shift.

In the build up to the Xmas holidays I was interviewed by two mainstream media outlets about the recently released (December 2021) Defence Assessment Report and last week’s 5 Eyes Communique that included New Zealand as a signatory. The common theme in the two documents was the threat, at least as seen through the eyes of NZ’s security community, that the PRC increasingly poses to international and regional peace and stability. But as always happens, what I tried to explain in hour-long conversations with reporters and producers inevitably was whittled down into truncated pronouncements that skirted over some nuances in my thought about the subject. In the interest of clarification, here is a fuller account of what is now being described as a “shift” in NZ’s stance on the PRC.

Indeed, there has been a shift in NZ diplomatic and security approaches when it comes to the PRC, at least when compared to that which operated when he Labour-led coalition took office in 2017. But rather than sudden, the shift has been signalled incrementally, only hardening (if that is the right term) in the last eighteen months. In July 2020, the the wake of the ill-fated Hong Kong uprising, NZ suspended its extradition treaty with Hong Kong, citing the PRC passage of the Security Law for Hong Kong and its negative impact on judicial independence and the “one country, two systems” principle agreed to in the 1997 Joint UK-PRC Declaration on returning Hong Kong to Chinese control. At the same time NZ changed its sensitive export control regime so that military and “dual use” exports to HK are now treated the same as if they were destined for the mainland.

In November 2020 NZ co-signed a declaration with its 5 Eyes partners condemning further limits on political voice and rights in HK with the postponment of Legislative elections, arrests of opposition leaders and further extension of provisions of the mainland Security Law to HK. The partners also joined in condemnation of the treatment of Uyghurs in Yinjiang province. In April 2021 Foreign Minister Nanaia Mahuta gave her “Dragon and Taniwha” speech where she tried to use Maori allegories to describe the bilateral relationship and called for NZ to diversify its trade away from overly concentrated partnerships, using the pandemic supply chain problems as an illustration as to why.

She also said that NZ was uncomfortable with using the 5 Eyes intelligence partnership as a public diplomacy tool. I agree completely with that view, as there are plenty of other diplomatic forums and channels through which to express displeasure or criticism. The speech did not go over well in part because NZ business elites reacted viscerally to a large tattooed Maori woman spinning indigenous yarns to a mainly Chinese and Chinese-friendly audience (and other foreign interlocutors further afield). From a “traditional” (meaning: white male colonial) perspective the speech was a bit odd because it was long on fable and imagery and short on “hard” facts, but if one dug deeper there were plenty of realpolitik nuggets within the fairy dust, with the proper context to the speech being that that Labour has an agenda to introduce Maori governance principles, custom and culture into non-traditional policy areas such as foreign policy. So for me it was the balancing act bookended by the trade diversification and 5 Eyes lines that stood out in that korero.

Less than a month later Prime Minister Ardern spoke to a meeting of the China Business Summit in Auckland and noted that “It will not have escaped the attention of anyone here that as China’s role in the world grows and changes, the differences between our systems – and the interests and values that shape those systems – are becoming harder to reconcile.” That hardly sounds like appeasement or submission to the PRC’s will. Even so, Mahuta and Ardern were loudly condemned by rightwingers in NZ, Australia, the UK and US, with some going so far as to say that New Zealand had become “New Xiland” and that it would be kicked out the 5 Eyes for being soft on the Chinese. As I said at the time, there was more than a whiff of misogyny in those critiques.

In May 2021 the Labour-led government joined opposition parties in unanimously condemning the PRC for its abuse of Uyghur human rights. The motion can be found here.

In July 2021 NZ Minister of Intelligence and Security Andrew Little publicly blamed China-based, state-backed cyber-aggressors for a large scale hacking attack on Microsoft software vulnerabilities in NZ targets. He pointed to intolerable behaviour of such actors and the fact that their operations were confirmed by multiple Western intelligence agencies. He returned to the theme in a November 2021 speech given at Victoria University, where he reiterated his concerns about foreign interference and hacking activities without mentioning the PRC by name as part of a broad review of his remit. Rhetorical diplomatic niceties aside, it was quite clear who he was referring to when he spoke of state-backed cyber criminals (Russia is the other main culprit, but certainly not the only one). You can find the speech here.

In early December 2021 the Ministry of Defense released its Defense Assessment Report for the first time in six years. In it China is repeatedly mentioned as the major threat to regional and global stability (along with climate change). Again, the issue of incompatible values was noted as part of a surprisingly blunt characterisation of NZ’s threat environment. I should point out that security officials are usually more hawkish than their diplomatic counterparts, and it was the Secretary of Defense, not the Minister who made the strongest statements about China (the Secretary is the senior civil servant in the MoD; the Minister, Peeni Henare, spoke of promoting Maori governance principles based on consensus and respect into the NZDF (“people, infrastructure, Pacifika”), something that may be harder to do than say because of the strictly hierarchical nature of military organisation. At the presser where the Secretary and Minister spoke about the Report, the uniformed brass spoke of “capability building” based on a wish list in the Report. Let’s just say that the wish list is focused on platforms that counter external, mostly maritime, physical threats coming from extra regional actors and factors rather than on matters of internal governance.

Then came the joint 5 Eyes statement last week, once again reaffirming opposition to the erosion of Hong Kong’s autonomy and its gradual absorption into the Chinese State. Throughout this period NZ has raised the issue of the Uyghurs with the PRC in bilateral and multilateral forums, albeit in a quietly diplomatic way.

I am not sure what exactly led to NZ’s shift on the PRC but, rather than a sudden move, there has been a cooling, if not hardening trend during the last eighteen months when it comes to the bilateral relationship. The decision to move away from the PRC’s “embrace” is clear, but I have a feeling that something unpleasant may have occurred in the relationship (spying? influence operations? diplomatic or personal blackmail?) that forced NZ to tighten its ties to Western trade and security networks. The recently announced UK-NZ bilateral FTA is one step in that direction. AUKUS is another (because if its spill-over effect on NZ defense strategy and operations).

What that all means is that the PRC will likely retaliate sometime soon and NZ will have to buckle up for some material hardship during the transition to a more balanced and diversified trade portfolio. In other words, it seems likely that the PRC will respond by shifting its approach and engage diplomatic and economic sanctions of varying degrees of severity on NZ, if nothing else to demonstrate the costs of defying it and as a warning to those similarly inclined. That may not be overly burdensome on the diplomatic and security fronts given NZ’s partnerships in those fields, but for NZ actors deeply vested/invested in China (and that means those involved in producing about 30 percent of NZ’s GDP), there is a phrase that best describes their positions: “at risk.” They should plan accordingly.

Along with the New Year, there is the real possibility that, whether it arrives incrementally or suddenly, foreign policy darkness lies on the horizon.

The unshackled straitjacket.

In the 1980s the political scientist Jon Elster wrote a book titled Ulysses and the Sirens where he uses the Homeric epic The Odyssey to illustrate the essence of democracy. In book 12 of The Odyssey, the enchantress Circe warns Ulysses of the dangers posed by the mythical Sirens, purportedly half women and half bird but in reality monsters, whose songs were irresistible to men and who endeavored to lure wayfarers to their deaths on the rocky cliff faces of the Siren’s island. Circe advised that only Ulysses should listen to their “honeyed song,” and that his men should plug their ears with beeswax while he be lashed to the mast of his ship after his men plugged their ears, and that even though he cried and begged them to untie him once he came to hear the Siren’s alluring tones, that he only be freed once his ship was far our of reach of the Siren’s voices. So it was, as Ulysses heeded her advice, made safe passage in spite of the temptress’s calls, and he and his crew proceeded on their decade-long voyage home from the Trojan Wars to Ithaca. As it turns out, it did not end well for all, which is a story for another day. (Thanks to Larry Rocke for correcting my initial mistaken read about their fate).