Much ether and pulp have been expended analysing the Daesh phenomenon and its consequences. The range and acuity of interpretations is broad yet often shallow or incomplete. Since it is a rainy weekend on Auckland’s west coast, I figured that I would alternate playing with the toddler with compiling a brief on the multiple interlocked layers that is the war of Daesh.

I refer to the irregular warfare actor otherwise known as ISIS, ISIL or IS as Deash because the latter is a derogatory term in Arabic and denies the group its claim to legitimacy as a state or caliphate. Plus, Isis is a common Arabic female name so it is insulting to Arab women to use it.

Much like the famed Russian dolls, the conflicts involving Daesh can be seen as a series of embedded pieces or better yet, as a multilevel chess game, with each piece or level interactive with and superimposed on the other. Working from the core outwards, this is what the conflict involving Daesh is about:

First, it is a conflict about the heart and soul of Sunni Islam. Daesh is a Wahabist/Salafist movement that sees Sunni Arab petroligarchies, military nationalist regimes such as those of Saddam Hussein, Bashar al-Asaad and Muammar al-Qaddafi, nominally secular regimes like those in Algeria, Egypt, Turkey and Tunisia, and moderate monarchies such as those of Jordan and Morocco as all being degenerate and sold out to Western interests, thereby betraying their faith. The overthrow of these regimes and the prevention of anything moderate (read: non-theocratic) emerging as their political replacement are core objectives for Daesh.

Secondly, Daesh is at the front of a Sunni-Shiia conflict. In significant measure funded by the Arab petroligarchies who opportunistically yet myopically see it as a proxy in the geopolitical competition for regional dominance with Iran and its proxies (such as Hizbollah) and allies (like the Syrian and post-Saddam Iraqi regimes), Daesh has as its second main objective eliminating the Shiia apostates as much as possible. To that can be added removing all ethnic and religious minorities for the Middle East, starting with the Levant. Because Daesh is racist as well as fundamentalist in orientation, it wishes to purge non-Arabs from its domain even if it will use them as cannon fodder in Syria and Iraq and as decentralised autonomous terrorist cells in Europe and elsewhere.

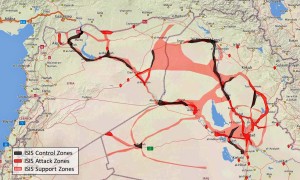

Thirdly, Daesh is engaged in a territorial war of conquest in Iraq and Syria, where it seeks to geographically situate its caliphate. This has allowed it to gain control over important oil processing facilities in Iraq and Syria and use the proceeds from the black-market sale of oil (including to the Assad regime!) to help fund its recruitment and weapons procurement efforts.

Fourth, Daesh is the source of inspiration, encouragement and sometimes training of decentralised, independent and autonomous urban guerrilla cells in Europe and elsewhere that use terrorism as the tactic of choice. The strategy is a variant of Che Guevara’s “foco” theory of guerrilla warfare whereby cadres receive common training in a secure safe haven then return to their home countries in order to exploit their knowledge of the local terrain (cultural, socio-economic, political as well as physical) in order to better carry out terrorist attacks with high symbolic and psychological impact. In this variant Daesh uses social media to great effective to provide ideological guidance and practical instruction to would-be domestic jihadis, thereby obviating the need for all of them to gain combat experience in the Middle East.

Like Lenin and Guevara, Daesh understands that its terrorism will attract the mentally unbalanced and criminally minded seeking a cause to join. Along with disaffected, alienated and angry Muslim youth, these are the new Muslim lumpenproletarians that constitute the recruitment pool for the guerrilla wars it seeks to wage in the Western world. In places like Belgium, France and arguably even Australia, that recruitment pool runs deep.

Fifth, through these activities Daesh hopes to precipitate a clash of civilizations between Muslims and non-Muslims on a global scale. Â It sees the current time much as fundamentalist Christians do, as an apocalyptic “end of days” moment. Its strategy is to fight a two-front war to that end, using the territorial war in the Middle East as a base for conventional and unconventional military operations while engaging in irregular war in Europe and elsewhere. The key of their military strategy is to lure Western powers into a broad fight on Muslim lands while getting them to overreact to terrorist attacks on their home soil by scapegoating the Muslim diaspora resident within them.

Daesh may be barbaric but its political and military leadership (made up mostly of Sunni Baathists from Iraq) is not stupid. It has not attacked Israel, knowing full well what the response will be from the Jewish state. In its eyes the confrontation with the Zionists must wait until the pieces of the end game are in place.

A critical component of Daesh’s strategy is the so-called “sucker ploy,” and it is being successful in implementing it. Basically, the sucker ploy is a tactic by which a weaker military actor commits highly symbolic atrocities in order to provoke over-reactions from militarily stronger actors that deepen the alienation from the stronger actor of core prospective constituencies of the weaker actor. That is exactly what has happened in places like the US, where opposition to the acceptance of Syrian refugees has become widespread in conservative political circles. It also is seen in the bans on refugees imposed by the Hungarian and Polish governments, and the clamour to halt refugee flows from conservative-nationalist sectors throughout Europe. We even see it in NZ on rightwing blogs and talkback radio, where the calls are to keep the Syrian refugees out even though no Syrian has ever done politically-motivated harm to a Kiwi (the projected intake is 750).

Sowing disproportionate fear, paranoia and the blind thirst for revenge amongst targeted populations is the bread and butter of the sucker ploy and by all indicators Daesh has done very well in doing so.

There is more to the picture but I shall leave things here and resume my asymmetric campaign versus the toddler.

One final thought. For the anti-Daesh coalition the fight must assume the form of a conventional war of territorial re-conquest in Syria and Iraq, run in parallel with a shadow urban counter-insurgency campaign in the West that is fought irregularly but which is treated judicially as a criminal matter, much like an anti Mafia campaign would be. Eliminating the territorial hold of Daesh in Syria and Iraq will remove their safe haven and training grounds as well as kill many of their fighters and leaders. That will help slow refugee flows and the recruitment of Westerners to the cause and facilitate the domestic counter-insurgency campaigns of Daesh-targeted states. The latter include better human intelligence gathering and intelligence sharing by and among erstwhile allies and adversaries in order to better counter dispersed terrorist plots.

Of course, the long-term solution to Daesh, al-Qaeda and other Islamicist groups is political reform in the Arab world and socio-economic reform in the Western world that respectively treat the root causes of  alienation and resentment within them.  So what is outlined in the previous paragraph is just a short-term solution.

In order for even that to happen, there has to be a tactical alliance between all actors with strategic stakes in the game: Russia, major Western powers, the Sunni Arab states and Turkey, the Syrian and Iraqi regimes, the Kurds, Iran and a host of irregular warfare actors including Hizbollah, the Free Syrian Army and assorted Islamicist groups not beholden to Daesh. It will be a hard coalition to cobble together, but the common threat posed by Daesh could just well force them to temporarily put aside their differences in favour of a workable compromise and military division of labour between them.

Of course, should that all occur and Daesh be defeated, then the old fashioned geopolitical chess game between Russia, the West, the Arabs, Kurds and Iranians can resume in Syria and Iraq. The conditions for that game depend on who emerges strongest from the anti-Daesh struggle.

Somewhere in the Kremlin Vladimir Putin is smiling.